After a mass extinction, such as the Hangenberg Event 359 million years ago, the oceans were dominated by significantly smaller fish for several tens of millions of years, while their larger cousins struggled and died off, according to the findings of a new study published in the journal Science.

The Hangenberg Event was a bioevent when large portions of the oceans became depleted in oxygen (O2).

In times of plenty, the big fish rule the seas, as do the larger animals on land and in the air. They should not feel too smug about their perceived superiority, however, because all it needs is a slight change in the environment, caused by an asteroid impact, a bioevent, or human activity for the meek (little animals) to inherit the Earth.

Many of the species that became extinct were large animals.

Many of the species that became extinct were large animals.

Study leader, Assistant Professor Lauren Sallan, of the University of Pennsylvania, explains that the Hangenberg Event triggered a drastic transformation of the Earth’s vertebrate community.

Smaller fish dominated for 40 million years

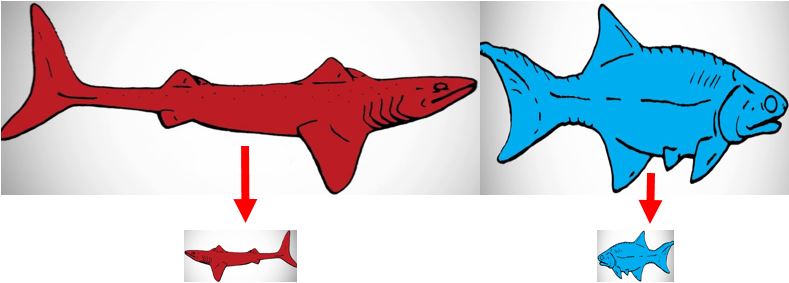

Before the Hangenberg Event, big creatures were the norm, but for 40 or more million years following the die-off, the oceans were taken over by armies of much smaller fish.

Prof. Sallan said:

“Rather than having this thriving ecosystem of large things, you may have one gigantic relict, but otherwise everything is the size of a sardine.”

The authors believe their findings, which suggest that smaller, faster-reproducing fish had an evolutionary edge over their larger cousins in the disturbed, post-extinction environment, may have implications for the patterns we observe in current fish populations, many of which are struggling due to overfishing.

The reasons behind the changes in the body sizes of animals over time have long been the subject of debate among evolutionary biologists and paleontologists (fossil scientists).

Following the Hangenberg Event, school-bus size fishes shrank to the size of sardines, and even apex predator sharks (on top of the food chain) went down to nearly that size. They stayed that way for nearly 40 million years.

Following the Hangenberg Event, school-bus size fishes shrank to the size of sardines, and even apex predator sharks (on top of the food chain) went down to nearly that size. They stayed that way for nearly 40 million years.

Many theories regarding animals’ body size over time

According to Cope’s rule, named after American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897), the body size of a particular group of species tends to become larger over time, because being big has evolutionary advantages, such as being better able to catch prey and less likely to be eaten by other creatures.

Other theories suggest that animals get larger in colder climates, or in the presence of higher O2 levels.

Another idea, called the Lilliput Effect, a term coined in 1993, holds that after mass extinctions, the trend shifts towards a reduction in body size (as far as survival is concerned). However, this theory has only been supported with a small number of species and is highly debated.

What effect did the Hangenberg Event have?

To sort out the body-size trends related to the Hangenberg Event, Prof. Sallan and co-author Andrew Galimberti, today a graduate student at the University of Maine, gathered and analyzed data on 1,120 fish fossils spanning from 419 to 323 million years ago.

They focused on body-size data from published papers, photographs, museum specimens, and bits of fossils for which, based on characteristics we know about the species, they could extrapolate a full size.

Their analysis of all these fossils back Cope’s rule – that vertebrates tend to gradually increase in body size during the Devonian period, from 419 to 359 million years ago.

Prof. Sallan said that by the end of the Devonian:

“There were fish called arthrodire placoderms with large slashing jaws that were the size of school buses, and there were relatives of living tetrapods, or land-dwelling vertebrates, that were almost as large.”

“You had some vertebrates that are small, but the majority of residents in ecosystems, from bottom dweller to apex predator, were a meter or more long.”

Then the mass extinction came, which destroyed much of life on Earth, wiping out over 97% of all vertebrate species.

Prof. Sallan and Mr. Galimberti found that after the extinction event, body size shrank and continued declining for at least 40 million years – much longer than they expected.

Prof. Sallan said:

“Some large species hung on, but most eventually died out. So the end result is an ocean in which most sharks are less than a meter and most fishes and tetrapods are less than 10 centimeters, which is extremely tiny. Yet these are the ancestors of everything that dominates from then on, including humans.”

Temperature and O2 levels had not effect on body size

To determine whether the current theories relating to body size and temperature or atmospheric O2 levels could explain their findings, they mapped the body-size trends against climate models over the time period.

Prof. Sallan said:

“There was no association with either temperature or oxygen, which overturns everything that has been assumed in vertebrates both today and in the past. Instead it tells us that these trends must be based entirely on ecological factors.”

The authors believe their results indicate that the mass extinction triggered a very long-term Lilliput Effect, in which smaller creatures were favored.

Prof. Sallan said:

“Before the extinction, the ecosystem is stable and thriving so that organisms can spend the time to grow to large sizes before they reproduce, for example. But, in the aftermath of the extinction, that ends up being a bad strategy in the long term. So tiny, fast-reproducing fish take over the entire world.”

Forest fires trigger a similar pattern in plants

The same happens with plant species after a disturbance. After a forest fire, for example, fast-growing grasses tend to be the first to colonize the area that burnt down, followed by shrubs – it is only later that the large trees start thriving.

While the forest-fire process occurs on a small scale and may only take a few decades, it matches the ecosystem and global-scale processes the authors observed as having occurred for a period of millions of years in the oceans.

With several fish populations today facing possible extinction, and with some ecologists concerned that Earth is on the brink of a 6th major extinction event, which this time is caused by humans, Prof. Sallan says their results should raise alarms about how long larger species might take to make a comeback.

Prof. Sallan said:

“It doesn’t matter what is eliminating the large fish or what is making ecosystems unstable. These disturbances are shifting natural selection so that smaller, faster-reproducing fish are more likely to keep going, and it could take a really long time to get those bigger fish back in any sizable way.”

In an Abstract in the journal the authors concluded:

“Disruption of global vertebrate, and particularly fish, biotas may commonly lead to widespread, long-term reduction in body size, structuring future biodiversity.”

Citation: “Body-size reduction in vertebrates following the end-Devonian mass extinction,” Lauren Sallan and Andrew K. Galimberti. Science. 13 November, 2015: 350 (6262), 812-815. DOI:10.1126/science.aac7373.