Top-secret documents belonging to Alan Turing, best-known for helping decipher the code created by German Enigma machines in World War II, have been found in a shed roof at Bletchley Park.

The papers were all scrunched up and stuffed into holes in the roof of Hut 6 to stop cold draughts (US English: drafts) and leaks from getting through. The discovery was made during a restoration at Bletchley Park, Churchill’s Secret Intelligence and Computers Headquarters in the Second World War.

The recovered documents are all that are left of the Banbury sheets, a system involving punching two cipher texts onto different sheets and then sliding them over one another and counting the holes that overlapped.

The Banbury sheets were used to decipher Nazi messages and helped the allied forces intercept naval communications.

After using the sheets, codebreakers were ordered to destroy them, according to wartime rules. Clearly they didn’t, but instead used some of them to block the draughts coming in through the roof in Hut 6.

Hut 6 was known to have poor insulation and a leaky roof. Conditions during the winter months could become uncomfortable for those working inside the shed.

Victoria Worpole, Director of Learning and Collections at Bletchley Park, said:

“It’s quite rare for us to find new paperwork because any that survived is in either our archive, at GCHQ or the National Archive, so to find actual materials that were used by the codebreakers, shoved between beams and cracks in the woodwork is really exciting.”

“We’ve had a conservator work on the materials to make sure we preserve them as best we can. It’s quite interesting to think that these were actual handwritten pieces of codebreaking, workings out.”

While restoration work was being carried out in Hut 6, workers also recovered a fashion article in a magazine, parts of an Atlas, and a pinboard.

In an interview with The Times, Bletchley Park Trust chief executive Ian Standen said the documents were discovered in September 2013. He said they would be thawed and then placed for public display.

Mr. Standen said:

“Discovering these pieces of code-breaking ephemera is incredibly exciting and provides yet more insight into how the code breakers actually worked.”

“The fact that these papers were used to block draughty holes in the primitive hut walls reminds us of the rudimentary conditions under which these extraordinary people were working.”

Who was Alan Turing?

Alan Mathison Turing (1912-1954), widely considered to be the father of artificial intelligence and theoretical computer science, was a British computer scientist, mathematician, cryptanalyst, logician, mathematical biologist and philosopher. He was also a marathon and ultra-distance runner.

Mr. Turing was influential in the development of computer science. He provided a formalization of the concepts of “computation” and “algorithm” with the Turing machine, which is considered a model of a general-purpose computer.

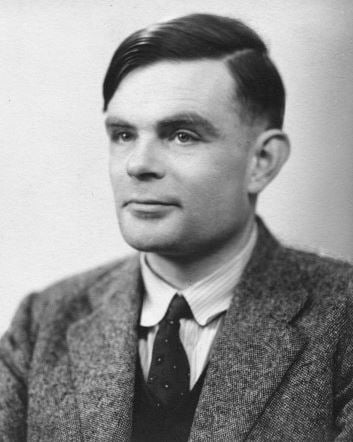

Alan Turing in 1951, three years before his death. (Image: Wikimedia)

During WWII, Mr. Turing worked at the UK’s codebreaking centre – the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire.

Some military historians claim the work at Bletchley Park shortened the duration of the war in Europe by more than two years.

In 1952, Mr. Turing was prosecuted for homosexual acts. At the time homosexual behavior was a crime in the UK. As an alternative to prison, he accepted treatment with oestrogen injections, i.e. chemical castration.

Just sixteen days before his 42nd birthday in 1954, Mr. Turing died of cyanide poisoning. While an inquest determined he had committed suicide, it has since been noted he may have died of accidental poisoning.

Following an online campaign, Prime Minister Gordon Brown made an official public apology on behalf of the British Government in 2009 for “the appalling way he was treated.” In 2013, The Queen granted him a posthumous pardon.

New book about the WWII female codebreakers

Six women, all of them now in their nineties, who worked as codebreakers at Bletchley Park during WWII – The Debs of Bletchley Park – returned to where they used to work as a book featuring their stories was launched in January.

The book – “The Debs of Bletchley Park and Other Stories” – was written by Bletchley Park’s chief historic advisor, Michael Smith.

They told the authors what life was like for them at the time, working at the secret location, as well as how it affected their personal lives. Their work was vital for the war effort, shortened the war and probably saved thousands of lives.