The capercaillie, also known as the wood grouse, has made a remarkable comeback in a part of Scotland – the spectacular population surge has been recognised by the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM), which has given a top award to Forest Enterprise Scotland.

Forest Enterprise Scotland has been awarded CIEEM’s prestigious Corporate Achievement Award for its outstanding 15-year successful effort to integrate the production of timber and recreation with capercaillie conservation.

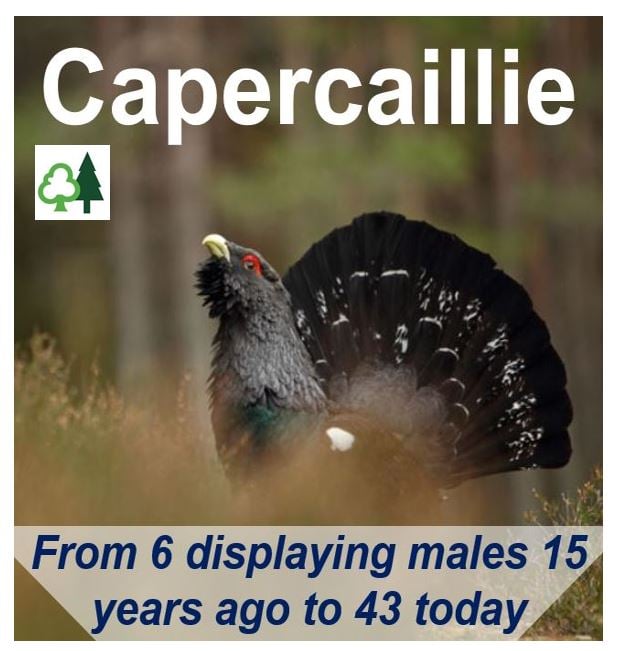

The number of displaying males – wood grouse that are actively breeding – has increased from just six at the start of Forest Enterprise Scotland’s programme fifteen years ago, to forty-three in 2016.

Could Forest Enterprise Scotland’s conservation model restore capercaillie populations in other parts of the country? (Image: scotland.forestry.gov.uk)

Could Forest Enterprise Scotland’s conservation model restore capercaillie populations in other parts of the country? (Image: scotland.forestry.gov.uk)

200+ capercaillie today in Strathspey

If there are 43 displaying males in the area now, it may mean that overall there are approximately 200 capercaillie on the National Forest Estate in Strathspey, north-eastern Scotland.

Species ecologist, Kenny Kortland, who works for Forest Enterprise Scotland, said regarding the organisation’s fifteen-year effort:

“Throughout this period we have actively managed the timber resource and have provided recreational opportunities for over 300,000 visitors every year. We have also carried out on-going research and this has shown that our forest management creates ideal habitat for the capercaillie.”

“These efforts appear to be working because the birds have shown a spectacular increase. In our view, this clearly indicates that caper can prosper in well managed, working forests. The key seems to be that thinning the forest to extract timber creates ideal habitat for capercaillie chicks, because breeding success has been high by contemporary standards.”

The male capercaillie is considerably larger and has completely different coloured feathers, compared to the female. According to the RSPB: “The UK capercaillie population has declined so rapidly that it is at very real risk of extinction (for the second time) and is a ‘Red List’ species.” (Images: Male – rspb.org.uk/Images. Female – rspb.org.uk/Images)

The male capercaillie is considerably larger and has completely different coloured feathers, compared to the female. According to the RSPB: “The UK capercaillie population has declined so rapidly that it is at very real risk of extinction (for the second time) and is a ‘Red List’ species.” (Images: Male – rspb.org.uk/Images. Female – rspb.org.uk/Images)

Predators and capercaillie populations growing

Wildlife experts at Forest Enterprise Scotland said it is interesting and great news that the capercaillie population is growing while the number of potential predators is also rising

They say that each of the predator groups are probably keeping certain species’ numbers down naturally, which in turn has had positive spin offs for the capercaillie’s survival status in the area.

Mr Kortland explained:

“We think that the various predators are controlling each other and this allows the capercaillie to thrive. For example, goshawks are recent colonists of these woods and they are eating a lot of crows, which eat capercaillie eggs. Similarly, foxes prey upon pine martens, which eat capercaillie eggs and young.”

“Many Forest Enterprise Scotland staff and partners have been involved in this project, which shows that an endangered species can flourish alongside people. We are all delighted to receive this award.”

What is happening at the National Forest Estate in Strathspey contrasts starkly with the fate of the species in other parts of the country, where its survival status continues to deteriorate alarmingly.

The capercaillie

The western capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), also known as simply capercaillie, heather cock or wood grouse, is the largest member of the grouse family. Males are about twice the size of females.

The species, which is renowned for its mating display, is found across Asia and Europe. In the United Kingdom, capercaillie can only be found in the pine forests of Scotland, where for several years it has been threatened with extinction.

Globally, the capercaillie is thriving – there are literally millions of them. However, their survival status in Scotland, the only part of the UK where any exist in the wild today, has deteriorated considerably over the past half century. (Images: UK map – RSPB. World Map – Wikipedia)

Globally, the capercaillie is thriving – there are literally millions of them. However, their survival status in Scotland, the only part of the UK where any exist in the wild today, has deteriorated considerably over the past half century. (Images: UK map – RSPB. World Map – Wikipedia)

Its global population, however, is categorized as ‘Least Concern’ – there are millions of them in Asia and Northern Europe.

It is a non-migratory sedentary bird that breeds across northern Europe and western and central Asia in mature conifer forests.

Where its survival status has deteriorated, its most serious threats are habitat degradation, particularly the conversion of diverse forests into single-species timber plantations.

It is one of the most sexually dimorphic in size in the world of birds today – males are considerably larger than females.

Males range from 29 to 33 inches (74 to 85 cm) in length, 35 to 49 inches (90 to 125 cm) in wingspan, and weigh on average 9.0 pounds (4.1 kg). Very large males can reach 39 inches (100 cm) and 15 pounds (6.7 kg) in length and weight respectively.

The male’s body feathers are grey to dark brown, while its breast feathers are dark metallic green. The feathers on its belly and undertail vary from black to white.

The female is tiny in comparison – her body from beak to tail is about 21-25 inches (54-64 cm) long, her wingspan is 28 inches (70 cm), and her weight ranges from 3.3 to 5.5 pounds (1.5 to 2.5 kg).

Her feathers on the upper parts are brown with black & silver barring, while on the underside they are lighter and buffish-yellow.

A male capercaillie mounting a hen. If other males are present within the lek, the alpha male mounts the female. (Image: journals.plos.org/plosone)

A male capercaillie mounting a hen. If other males are present within the lek, the alpha male mounts the female. (Image: journals.plos.org/plosone)

Both the cock and hen have feathered legs, especially during the winter for protection against cold.

The capercaillie feeds on a variety of foods, including berries, grasses, leaves, buds and insects. During the winter, conifer needles make up most of its diet.

Adults are nearly exclusively herbivores, while young chicks, which are dependent on high-protein foods in the first weeks, mainly prey on insects.

Courting and reproduction

Courting starts in March or April, depending on spring temperatures and altitude. Most of the courting season is spent by males defending their territory.

Tree courting – on a thick branch of a lookout tree – begins as soon as the Sun comes up in the morning. The male (cock) raises and fans his tail feathers, points his beak up to the sky, holds out his wings in a drooped posture, and starts his typical aria to impress the hens.

Its courting song consists of a series of double-clicks that sound like a bouncing ping-pong ball. The double-clicks gradually accelerate into a popping sound like a cork being pulled out of a bottle – this is followed by scraping sounds.

It is not until the end of the courting period that hens enter the courting grounds, also known as leks (Norwegian for ‘play’). When the females are present, the males continue courting, but on the ground.

The male flies down from his courting tree, finds an open space nearby, and continues his display. The females crouch and utter begging sounds, a signal that they are ready to be mounted.

There is also a shorter courting peak in autumn, which serves to delineate territorial boundaries for the winter months and next year’s season.

Females lay on average eight eggs – this number can range from four or five to twelve. The eggs start hatching after 26 to 28 days, depending on the weather and altitude.

Video – Capercaillie

In this RSPB video, you can see a male doing his courtship display surrounded by several hens.

Capercaillie from The RSPB on Vimeo.