Cockroaches have incredibly strong jaws that in relative terms are about five times stronger than the force human beings can generate from their jaws. When chewing their way through hard or tough materials, such as wood, their bite force is 50 times stronger than their own body weight.

In a new study, scientists from the University of Cambridge in England, Friedrich Schiller University, and the University of Stuttgart, both in Germany, explained in the journal PLOS ONE that cockroaches use a combination of slow and fast twitch muscle fibres to give their mandibles a ‘force boost’ so they can chew through tough materials.

The slow twitch muscle fibres are only activated when the insects have to chew on tough materials that require repetitive, hard biting.

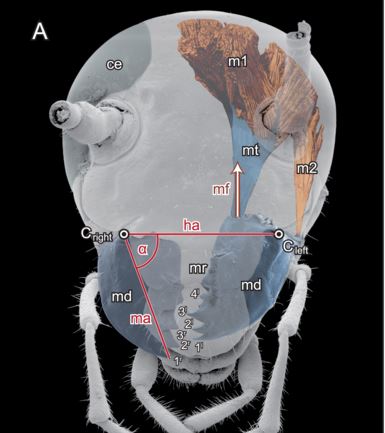

Morphology of the cockroach head from a μCT scan with emphasis to the mandibles (coloured light blue) and their driving muscles (light red). (Image: PLOS ONE)

Morphology of the cockroach head from a μCT scan with emphasis to the mandibles (coloured light blue) and their driving muscles (light red). (Image: PLOS ONE)

Insects crucial for material cycles and ecological balance

Lead author, Tom Weihmann, from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, said:

“As insects play a dominant role in many ecosystems, understanding the amount of force that these insects can exert through their mandibles is a pivotal step in better understanding behavioural and ecological processes and enabling bioinspired engineering.”

“Insects provide a major part of the faunal biomass in many terrestrial ecosystems. Therefore they are an important food source but also crucial as decomposers of plants and animals. In this way they are crucial for material cycles and the ecological balance.”

“Ours is the first study to measure the bite forces of ordinary insects, and we found that the American cockroach, Periplaneta americana, can generate a bite force around 50 times stronger than their own body weight. In relative terms that’s about five times stronger than the force a human can generate with their jaws.”

Insects have powerful mandibles

Previous studies have mainly concentrated on the biting action of larger animals which have lots of teeth and grind their food, catch prey or defend themselves. But cockroaches and other insects have different biting mouthparts – they have a pair of powerful, horizontally-aligned bladelike jaws called mandibles.

Side view of the general setup with the fixated specimen at the right and the force transducer at the left side. (Image: www.cam.ac.uk)

Side view of the general setup with the fixated specimen at the right and the force transducer at the left side. (Image: www.cam.ac.uk)

Insects’ mandibles play an important role in their lives – they are used for digging, defence, feeding their young, transport, and shredding food.

The mandibles are attached to the insect’s head capsule, which consists of thin multi-layered cuticle and forms a sophisticated structure within its exoskeleton. The driving muscles for all mouth parts are enclosed in the head capsule, along with several other vital organs of the digestive and central nervous systems.

Not much room in their heads for jaw muscles

With so many things packed in a very small area, there is little room for the muscles required to operate the scissor-like mandibles. Many insects have muscles with slanting fibres that minimize the amount of thickening that occurs when they contract.

According to Dr. Weihmann, cockroaches have the perfect model system when it comes to investigating biting. “(They are) extraordinarily ordinary insects with regard to their mouthparts and biting abilities,” he said.

The American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) is known colloquially as the waterbug, even though it is not an aquatic creature. It is the largest species of common cockroach, and is generally considered a pest.

The American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) is known colloquially as the waterbug, even though it is not an aquatic creature. It is the largest species of common cockroach, and is generally considered a pest.

The scientists measured the force of 300 bites made by cockroaches across a wide range of mandible opening angles.

Cockroaches are able to exert various levels of force with their bites, they found, from short, weak bites to incredible powerful bites that lasted much longer.

Dr. Weihmann explained:

“The weaker, shorter bites were generated by relatively fast muscle fibres, while the longer, stronger bites were driven by additional muscle fibres that take time to reach their maximum force. These slower muscle fibres give the mandibles a force boost to allow them to exert up to 0.5 Newtons during sustained grasping or chewing.”

“The employment of slow muscle fibres allows very efficiently generated muscle forces with only a minimum of cross section area, and therefore head volume, required.”

Cockroach bite may inspire engineering techniques

The researchers believe their study could eventually contribute towards the creation of interesting applications for bioinspired engineering. They plan to gain a better understanding of how the delicate head capsule structures withstand such powerful forces during the cockroach’s lifetime.

Dr. Weihmann said:

“It is interesting whenever forces have to be transferred within small hollow capsules, particularly if actuators such as tiny motors, advanced piezo-electric actuators or other sophisticated drives need to be attached to the inner sides of the structure, just like mandible muscles do.”

“With increasing miniaturisation, such designs will become increasingly important. Recent technical implementations in this direction are for instance micro probes inserted into blood vessels or micro surgical instruments.”

The research was funded by the Daimler and Benz Foundation and the German Research Foundation.

Citation: “Fast and powerful: Biomechanics and bite forces of the mandibles in the American cockroach Periplaneta Americana,” Tom Weihmann, Lars Reinhardt, Kevin Weißing, Tobias Siebert and Benjamin Wipfler. PLOS ONE. November 11, 2015. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0141226.