Evolution tends to favor size, paleobiologists at Stanford University believe. Their latest research suggests that the majority of animal lineages tend to evolve toward larger sizes over millions of years.

Associate Professor, Jonathan Payne, who works at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, said:

“We’ve known for some time now that the largest organisms alive today are larger than the largest organisms that were alive when life originated or even when animals first evolved.”

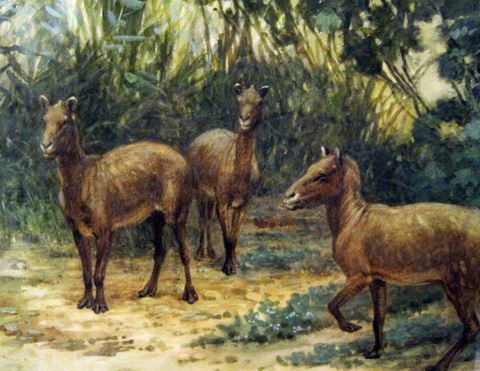

Eohippus genus of 50 million years ago, the ancestor of the modern horse, was not bigger than a dog. (Image: Wikipedia)

This latest study has been published in the journal Science (citation below), February 20 issue.

Scientists were not sure, however, whether the average size of animals has been changing over the past few million years, and if they have, whether that is part of a trend, or directionality, in body-size evolution.

Prof. Payne said:

“It’s not something that you can know by just studying living organisms or extrapolating from what you see over short time scales. If you do that, you will absolutely be wrong about the rate, and possibly also the direction.”

Sea animals 150 times bigger today

The scientists found that marine creatures today are on average 150 times bigger than their ancient ancestors 542 million years ago.

Dr. Noel Heim, a postdoctoral researcher in Payne’s lab, said:

“That’s the size difference between a sea urchin that is about 2 inches long versus one that is nearly a foot long. This may not seem like a lot, but it represents a big jump.”

They also found that the growth in body size that has occurred since living beings first appeared in fossil records about 550 million years ago is not due to all animal lineages continuously growing larger, but rather the diversification of organism groups that were already larger than other groups early on in the history of animal evolution.

This is something they did not know before, Prof. Payne explained. “For reasons that we don’t completely understand, the classes with large body size appear to be the ones that over time have become differentially more diverse.”

Prof. Payne (right) and Dr. Heim standing next to stacks of the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. (Credit: courtesy of Noel Heim)

Testing Cope’s rule

Cope’s rule, named after Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897), an American paleontologist and comparative anatomist, as well as a noted herpetologist and ichthyologist, states that animal lineages tend to evolve toward bigger sizes over time.

Mr. Cope noticed that terrestrial mammals such as horses generally got bigger over time. Horses can be traced to the Eohippus genus of 50 million years ago – an animal that was no bigger than a dog.

Paleontologist have tried to test Cope’s rule in several animal groups, with mixed conclusions. Dinosaurs and corals appear to follow Cope’s rule, but not insects and birds. Birds, which evolved from dinosaurs, got lighter and smaller over time with the necessity of flight.

Consequently, several scientists had suggested that the pattern observed in land mammals might just be a statistical one resulting from random, non-selective evolution (neutral drift).

Dr. Heim said:

“It’s possible that as evolution proceeds, there really is no preference for being larger or smaller. What appears to be an increase in average body size may be due to neutral drift.”

Study focused on marine life

The scientists set out to determine whether Cope’s rule applied to marine life with the most thorough test yet. They enlisted the help of colleagues, college students and even high school interns, to search through the scientific records and compiled a dataset including over 17,000 groups, or genera, of marine animals spanning five major phyla – Mollusks, Chordates, Arthropods, Brachiopods, and Echinoderms – over the past 542 million years.

Dr. Heim said:

“Our study is the most comprehensive test of Cope’s rule ever conducted. Nearly 75 percent of all of marine genera in the fossil record and nearly 60 percent of all the animal genera that ever lived are included in our dataset.”

The researchers used the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology (TIP), published by the Geological Society of America and the University of Kansas Press, a huge, 50-volume book set that includes detailed data about every invertebrate animal genus with a fossil record known to science.

The team poured through photographs and illustrations of fossils in the TIP and was able to calculate and analyze body size and volume of 17,208 different types of marine creatures.

Larger animals tended to become more diverse

Prof. Payne and colleagues soon spotted a trend: not all classes-groups of related species and genera-of animals trended toward bigger size. However, the larger ones tended to become more diverse than the smaller ones over time.

The researchers suggest this is due to several advantages associated with being bigger, such as the ability to capture larger prey, faster speed, and being able to burrow more deeply and efficiently in sediment.

Larger marine animals tended to become more diverse, the researchers found.

Dr. Heim said “It’s really a story of the survival and diversification of big things relative to small things.”

The scientists wanted to find out what could be driving these trends toward larger body sizes. They fed their measurement data into a computer model designed to simulate body-size evolution.

Starting with the smaller species in each phylum, the model simulated how their bodies would change as they evolved into new species.

Dr. Heim said:

“As time marches forward, each species is assigned some probability of producing a new species, of remaining the same, or of going extinct, at which point it drops out of the race.”

On the creation of a virtual new species, the model assigned the new creature a body size that could be either smaller or larger than its ancestor.

Several simulations were run, each with different assumptions. In one of the simulations, for example, a neutral drift model of evolution was assumed, in which body size changes randomly without affecting the species’ survival.

Another scenario assumed natural selection (active evolution) of body size, in which being bigger confers certain survival benefits and is consequently more likely to propagate through generations.

The scientists found that the neutral drift simulation could not explain the body size patterns observed in the fossil records.

Dr. Heim said:

“The degree of increase in both mean and maximum body size just aren’t well explained by neutral drift. It appears that you actually need some active evolutionary process that promotes larger sizes.”

Prof. Payne and colleagues believe the huge database they compiled will be useful for researchers seeking answers to several questions, including whether creatures near the equator are bigger or smaller than those living at higher latitudes.

Prof. Payne said:

“The discovery that body size often does evolve in a directional way makes it at least worth asking whether we’re going to find directionality in other traits if we measure them carefully and systematically.”

Citation: “Cope’s rule in the evolution of marine animals,” Noel A. Heim, Matthew L. Knope, Ellen K. Schaal, Steve C. Wang, and Jonathan L. Payne. Science 20 February 2015: 347 (6224), 867-870. [DOI:10.1126/science.1260065]