Extremophiles are organisms that thrive in geochemically and physically extreme conditions including boiling liquid, super acid pools, extremely low temperatures, and even the vacuum and radiation of outer space, as opposed to mesophiles that only thrive in temperatures between 20°C and 40°C or neutrophiles that require neutral pH environments.

The American Museum of Natural History has an exhibition – Life at the Limits – where you can learn about these organisms that thrive in extreme conditions.

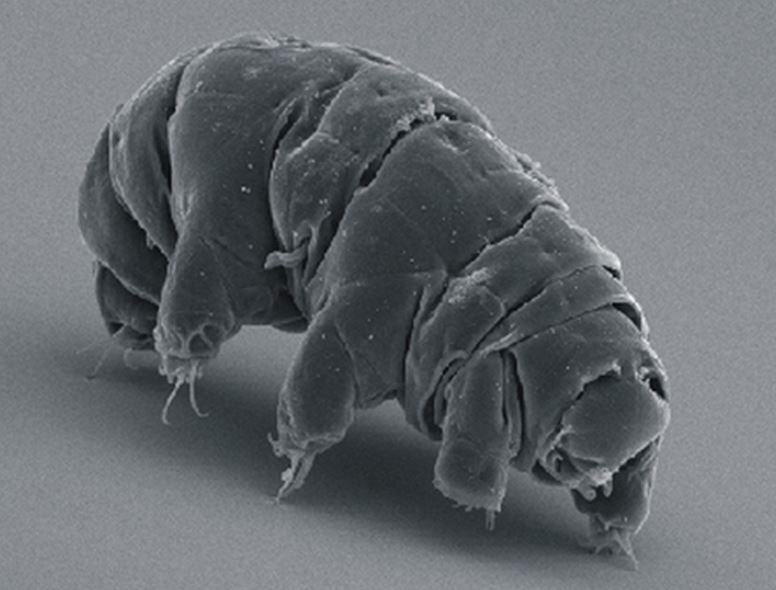

Tardigrades, eight-legged micro-animals that live in water, resemble little fat cushion piglets with vacuum-cleaner spout-like mouths – are also known as moss piglets. Since first discovered by German pastor Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773, these tiny creatures have charmed and astonished biologists.

The tough Tardigrade can enter a state known as ‘cryptobiosis’ in which it is nearly impossible to kill. (Image: American Museum of Natural History)

At the exhibition you can see Tardigrades as 10-foot models. Mr. Goeze first called them ‘kleiner Wasserbär’ (German for little water bear).

A few years later Lazzarro Spallanzini, an Italian naturalist, named them ‘tardi grada’ (slow-steppers), and provided the first description of the incredible transformation tardigrades undergo when under extreme environmental stress.

Tardigrades, which have been around for over 600 million years, are amazingly successful organisms. There are more than 1,000 species, which can be found across the globe, on land, where they cling to moss or lichens, and in fresh and sea water.

They are very common in moderate climates. However, terrestrial tardigrades can also thrive in places virtually no other lifeform can survive, such as Antarctica’s McMurdo Valleys, said to be the driest and coldest desert on Earth.

In order to survive in the mosses of Antarctica, and even in more mild places where their habitats can suddenly suffer sudden water loss, tardigrades have evolved a fascinating ability.

Tardigrade’s metabolism nearly stops completely

When their environment suddenly becomes inhospitable, whether from extreme declines in temperature, increases in salinity, or rapid drying, they defy death be imitating it. Their whole metabolism winds down in a reversible process called cryptobiosis – which literally means, hidden life. In other words, the organism’s metabolic activities come to a reversible virtual standstill.

Scientists say there is still much to learn about how exactly tardigrades become cryptobiotic when faced with extreme conditions.

In 1776, Spallanzini described the dramatic change the organism undergoes in response to lack of water (anhydrobiosis).

The animal starts off by curling into itself, tucking its head and eight limbs inside its body. It sheds over 95% of the water in its body, shriveling into a blob, known as a tun because it looks like a beer barrel.

The famously hardy tardigrade species Milnesium tardigradum survived space. (Image: American Museum of Natural History)

While shedding most of its water, tardigrade produces a sugar to protect its internal structures from fatal damage. Its metabolism slows down to less than 0.01% of normal activity as the animal virtually goes into stasis, until conditions improve. “Just add water, and these ‘barrels’ transform back into active ‘bears,’” the Museum wrote.

As tuns, tardigrades seem lifeless – and virtually indestructible. Scientists have exposed tuns to extremes of temperature and pressure, toxic concentrations of gasses including carbon monoxide. In every case, the little animal sprang back to life as soon as water was resupplied.

The European Space Agency sent two species of tardigrades into low Earth orbit on the FORON-M3 mission in 2007. The tuns continued to amaze by surviving the one-two punch of solar radiation and space vacuum.

Ten-foot models of tardigrades plus other incredibly resilient animals can be seen in the Life at the Limits exhibition at the American Museum of Natural History as from April 4th. Entrance is free for Members.

About the exhibition

Imagine being able to hold your breath for 90 minutes, enduring temperatures above 300°F (149°C) and below -458°F (-272°C), or appear to cheat death by repeatedly cloning yourself.

“Life at the Limits: Stories of Amazing Species explores the diverse and sometimes jaw-dropping strategies animals and plants employ to find food, fend off predators, reproduce, and thrive in habitats many would find inhospitable, even lethal.”

The exhibition has a climbable beetle. (Image: American Museum of Natural History)

The exhibition is overseen by Curator John Sparks, an ichthyologist (fish scientist), and Curator Mark Siddal, a parasitologist. It introduces visitors to bizarre mating calls, incredible examples of parasitism and mimicry, and other extraordinary means of survival, using specimens, interactive exhibits, videos and models.

“Live animals on display include the surprisingly powerful mantis shrimp; the jet-powered nautilus; and the axolotl, an entirely aquatic salamander that breathes through external gills. Life at the Limits tells the stories of these and many more creatures across the tree of life—and their unusual approaches to the challenges of living on Earth,” the Museum informs.

Video – Life at the Limits