Rescheduling can mean either the changing of the time at which a planned event(s) will happen, as in the rescheduling of train departure times during a weather emergency or the renegotiating of the terms of a loan.

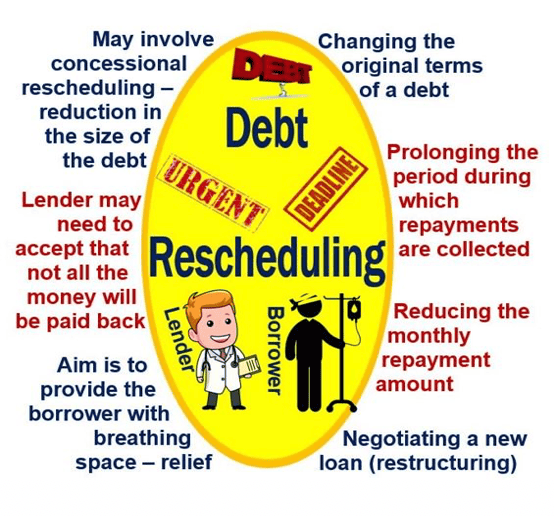

If a loan is rescheduled, it means that the original arrangement for repayments is altered, typically because the borrower is finding it difficult to pay back the lender.

In other words, rescheduling, often referred to as debt rescheduling, is a way in which the repayment of debts may be reorganized. The borrower might be an individual, company, organization, or even a country.

Rescheduling, which is sometimes called loan modification, may be in the form of:

- A combination of lower interest payments but a longer period during which they are collected.

- Arranging for a later repayment date.

- Lowering the interest payments but raising how much eventually has to be paid.

- Negotiating a new loan (usually called debt restructuring).

In some cases of loan modification, the lender – usually a bank, country, or international agency – needs to accept that it will lose financially; it won’t get all its money back.

The aim of debt rescheduling is to provide the borrower with relief or breathing space when required, due to perhaps an economic recession, job loss, illness or some other unforeseen personal event.

According to the Financial Times’ glossary of terms, to define ‘debt rescheduling’ is:

“An agreed delay in the repayment of a debt, usually applying to both interest and principal payments, and also often involving a renegotiation of the terms.”

Rescheduling and the Paris Club

The Paris Club, also called the Club de Paris, is an informal group of rich **creditor nations that try to find coordinated and sustainable solutions for payment problems that **debtor nations experience.

** A creditor nation is the one that is owed money, while the debtor nation owes money. When I borrow money from my bank, the bank is the creditor and I am the debtor.

As debtor nations undertake reforms to stabilize or improve their macroeconomic and financial situations, Paris Club creditors provide a debt treatment – which sometimes may involve rescheduling – that is appropriate to their situation.

Some nations may be offered concessional rescheduling – a reduction in their debt-service obligation over a set period. To ‘service’ a debt means to pay the required amount on the principal and interest of a loan, i.e. to keep up with your monthly or quarterly repayments.

The Paris Club describes itself as follows:

“The Paris Club is an informal group of official creditors whose role is to find coordinated and sustainable solutions to the payment difficulties experienced by debtor countries.”

“As debtor countries undertake reforms to stabilize and restore their macroeconomic and financial situation, Paris Club creditors provide an appropriate debt treatment. Paris Club creditors provide debt treatments to debtor countries.”

LDC Debt Crisis of the 1980s

LDC stands for Less Developed Country. The LDC Debt Crisis started in 1982, when Mexico, Brazil and some other Latin American nations confronted a combination of low commodity prices and high interest rates.

The LDCs declared that they were unable to service commercial bank loans worth hundreds of billions of dollars. It was not long before the problem spread across the world.

As most of the debtors’ economies at the time were dependent on commercial bank financing, repeated debt rescheduling and the resulting perception of insolvency triggered a lost decade with virtually no GDP (gross domestic product) growth.

During that lost decade, capital flows and voluntary international credit to these countries and their private sectors were significantly interrupted.

Until 1988, debtor countries and their commercial bank creditors engaged in round-after-round of rescheduling and restructuring literally thousands of private sector and foreign debts.

There was a belief that the problems and difficulties that these countries were facing would soon pass and that their economies would rebound.

In March 1989, Nicholas F. Brady, the then US Treasury Secretary, articulated a plan which became known as the Brady Plan. It was designed to address the LDC crisis.

Unfortunately, by the time Nicholas Brady announced the plan – seven years after the LDC debt crisis hit – most debtor nations were no closer to financial health. It became clear that many loans would never be repaid in full, no matter how many rescheduling arrangements were made.

What these countries needed in order to be able to get their fragile economies back on their feet – so that they could regain access to the global capital markets – was debt relief.

According to the EMTA (Emerging Markets Traders Association):

“The basic tenets of the Brady Plan were relatively simple and were derived from common practices in domestic U.S. corporate work-out transactions: (1) bank creditors would grant debt relief in exchange for greater assurance of collectability in the form of principal and interest collateral; (2) debt relief needed to be linked to some assurance of economic reform and (3) the resulting debt should be more highly tradable, to allow creditors to diversify risk more widely throughout the financial and investment community.”

Each Brady issue was unique, because the rescheduling process proceeded on a case-by-case basis. However, most Brady restructurings included two options for the debt holders – the exchange of loans for either Discount Bonds or Par Bonds.

As EMTA explained:

“Par Bonds resulted from an exchange of loans for bonds of equal face amount, with a fixed, below-market rate of interest, allowing for long-term debt service reduction by means of concessionary interest terms.”

“Discount Bonds resulted from an exchange of loans for a lesser amount of face value in bonds (generally a 30-50% discount), allowing for immediate debt reduction, with a market-based floating rate of interest.”

“The principal of both Par and Discount Bonds was secured at final maturity by a pledge of zero-coupon instruments which, in the case of Par and Discount Bonds denominated in U.S. dollars, were U.S. Treasury securities. A portion of the interest payable on Par and Discount Bonds (generally from 12 to 24 months coverage) was also secured by the pledge of high-grade investment securities.”

Mexico, which in August 1982 had been the first country to start negotiating with its commercial bank creditors, was also the first country to restructure under the Brady Plan in 1989.

Bonds were issued in an aggregate face amount of more than $160 billion by Vietnam, Venezuela, Uruguay, Russia, Poland, the Philippines, Peru, Panama, Nigeria, Mexico, Jordan, Ivory Coast, Ecuador, the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, Bulgaria, Brazil and Argentina.

The Brady Plan was immensely successful. Not only did it allow participating nations to negotiate considerable reductions in their overall debt levels and debt service obligations, it also succeeded in shifting sovereign risk from commercial bank portfolios more widely across the investment and financial communities.

The Brady Plan also encourage several emerging economies to adopt and pursue ambitious and effective economic reform programs.

EMTA added:

“Finally, the Brady Plan has enabled many emerging market countries to regain access to the international capital markets for their financing needs.”

Rescheduling vs. restructuring a loan

Many newspaper, articles and other texts use both these terms – sometimes with the same meaning. Technically, there is a difference. Restructuring is not that different from ‘rescheduling’, but it involves a much bigger change.

Restructuring involves a completely new process which includes all the components of ‘rescheduling’. When restructuring a loan, all the documents need to be modified – in that sense, we could say that restructuring is effectively a new loan.

If some of the debt is written off – this is more restructuring than rescheduling. However, as more and more journals and newspapers use the two terms interchangeably, the difference between them is becoming more blurred.

IbpExam.blogspot, a blog for bankers and students of banking, makes the following comment regarding debt restructuring:

“A fully secured standard/ sub-standard/ doubtful loan can be restructured by rescheduling of principal repayments and/or the interest element. The amount of sacrifice, if any, in the element of interest, is either written off or provision is made to the extent of the sacrifice involved.”

“The sub-standard accounts/doubtful accounts which have been subjected to restructuring, whether in respect of principal installment or interest amount are eligible to be upgraded to the standard category only after a specified period.”