Global populations of large herbivores are declining, especially in parts of Asia and Africa, making it more likely that some of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth will have growing areas of ‘empty landscape’, says a new study published in the academic journal Science Advances.

In this latest study, led by William Ripple, distinguished professor in the College of Forestry at Oregon State University, large herbivores include those weighing more than 100 kilograms (220 lbs) on average.

Prof. Ripple and colleagues from the US, UK, South Africa, Brazil and Australia carried out a comprehensive analysis of data on the largest herbivores on Earth, including endangerment status, key threats, and the ecological consequences of dwindling populations.

Source: advances.sciencemag.org.

They say that the populations of tapirs, elephants, camels, zebras and rhinoceroses are either declining or threatened with extinction in forests, deserts, savannahs and grasslands.

Prof. Ripple and team concentrated on seventy-four large herbivore species and concluded that “without radical intervention, large herbivores (and many smaller ones) will continue to disappear from numerous regions with enormous ecological, social, and economic costs.”

This study followed a previous one, which Prof. Ripple also led, on large-carnivore decline. He said large-carnivore populations go hand-in-hand with those of their herbivore prey.

Hunting by humans and habitat change

Prof. Ripple said:

“I expected that habitat change would be the main factor causing the endangerment of large herbivores. But surprisingly, the results show that the two main factors in herbivore declines are hunting by humans and habitat change. They are twin threats.”

The researchers refer to a study of the decline of animal populations in tropical forests published in BioScience in 1992. Author Kent H. Redford, who at the time was a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Florida, first coined the term ‘Empty Forest’.

While soaring trees and other plant life may exist, Redford wrote, the loss of forest fauna posed a serious, long-term threat to those ecosystems.

Source: advances.sciencemag.org.

From ‘empty forest’ to ‘empty landscape’

In this study, Prof. Ripple and co-researchers went one step further. “Our analysis shows that it goes well beyond forest landscapes,” they said, “to savannahs and grasslands and deserts. So we coin a new term, the Empty Landscape.”

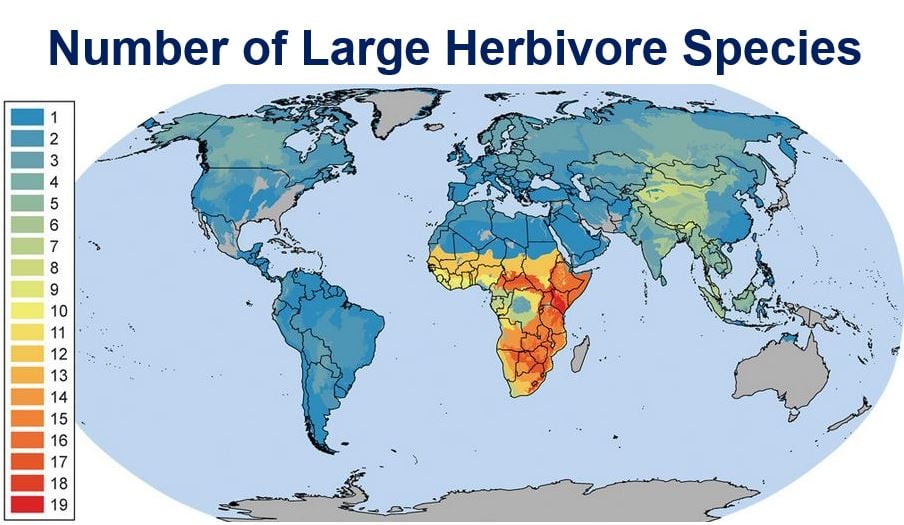

Terrestrial herbivores exist in every continent except Antarctica. As a group they encompass approximately 4,000 known species and live in several different types of ecosystems.

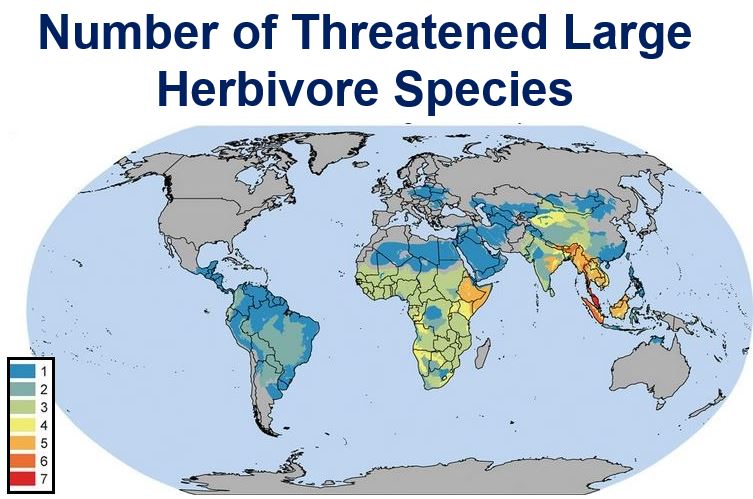

The greatest number of threatened large herbivores live in developing nations, especially Africa, India and Southeast Asia, the authors explained.

Europe has only one endangered large herbivore – the European bison. There are none in North America, which according to the authors “already lost most of its large mammals through prehistoric hunting and habitat changes.”

Twenty-five of the biggest wild herbivores occupy today an average of just 19% of their historical ranges. Since 1980, competition with livestock production has tripled worldwide. This has reduced herbivore access to water, forage and land, and also increased diseases transmission risks.

A European Bison, the only endangered large wild herbivore in Europe. (Image: Oregon State University)

Hunting of herbivores

The hunting of herbivores is fuelled by the global trade in animal parts and meat consumption, the authors wrote. Approximately 1 billion people today subsist on wild meat.

Prof. Ripple said:

“The market for medicinal uses can be very strong for some body parts, such as rhino horn. Horn sells for more by weight than gold, diamonds or cocaine.”

In 2011, Africa’s western black rhinoceros was declared extinct.

Co-author Professor Tall levi, who works in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife at Oregon State University, said the causes of the reduction in large herbivore populations “are difficult to remedy in a world with increasing human populations and consumption.”

Prof. Levi added:

“But it’s inconceivable that we allow demand for horns and tusks to drive the extirpation of large herbivores from otherwise suitable habitat. We need to intensify the reduction of demand for such items.”

Other parts of wild ecosystems affected

If large herbivore populations are dwindling, it probably means that other parts of wild ecosystems will also diminish, the researchers wrote.

The likely consequences include declining food sources for tigers, lions and other large carnivores, more frequent and intense wildfires, reduced seed dispersal for plants, slower cycling of nutrients from plants to soil, and changes in habitat for smaller animals such as birds, amphibians and fish.

Prof. Ripple said:

“We hope this report increases appreciation for the importance of large herbivores in these ecosystems. And we hope that policymakers take action to conserve these species.”

Coordinated effort required

In order to gain a better understanding of the likely consequences of large herbivore decline, the researchers call for a coordinated research effort concentrating on threatened species in developing nations.

Solving large herbivore population decline must include the involvement of local people, they emphasized.

The authors wrote:

“It is essential that local people be involved in and benefit from the management of protected areas. Local community participation in the management of protected areas is highly correlated with protected area policy compliance.”

Citation: “Collapse of the world’s largest herbivores,” William J. Ripple, Thomas M. Newsome, Christopher Wolf, Rodolfo Dirzo, Kristoffer T. Everatt, Mauro Galetti, Matt W. Hayward, Graham I. H. Kerley, Taal Levi, Peter A. Lindsey, David W. Macdonald, Yadvinder Malhi, Luke E. Painter, Christopher J. Sandom, John Terborgh, and Blaire Van Valkenburgh. Science Advances Vol. 1 no. 4 e1400103. Published 1 May, 2015. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1400103.