The National Trust have called on the UK government to use Brexit as an opportunity to replace the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy of farming subsidies with a system that rewards farmers who manage land in a nature-friendly way.

The conservation charity of 4 million members says reform is “essential to reverse decades of damage to the countryside and the headlong decline of species.”

Dame Helen Ghosh, Director General of the National Trust, speaks this week about the need for farming subsidy reform at a Countryfile Live event at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire. She says: “Taxpayers should only pay public subsidy to farmers in return for things that the market won’t pay for but are valued and needed by the public.

“Whatever your view of Brexit, it gives us an opportunity to think again about how and why we use public money to create the countryside we want to hand on to future generations.”

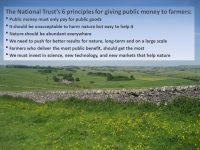

The National Trust are calling on the UK government to use Brexit as an opportunity to replace the £3.1 billion a year farmers get from the EU in subsidies with a system that is more nature-friendly. They propose six principles for deciding how public money should be used to subsidize farmers.

The National Trust are calling on the UK government to use Brexit as an opportunity to replace the £3.1 billion a year farmers get from the EU in subsidies with a system that is more nature-friendly. They propose six principles for deciding how public money should be used to subsidize farmers.

Common Agricultural Policy

Under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), British farmers currently receive £3.1 billion a year in direct subsidies. This is about double the total income farmers earn from their businesses alone, and represents about 60 percent of all the payments the UK receives from the EU.

About £600 million of the CAP subsidy is for schemes to support wildlife and the environment. The rest is allocated by size of farm.

The National Trust, which owns 250,000 hectares of land managed by 1700 tenant farmers, also benefits significantly from subsidies, says Ghosh. They receive about £11 million a year – £3 million in direct subsidy and £8 million for environmental stewardship schemes.

“But we spend all of the money we get on conservation – and indeed accept that in the future the amount of support we get might well fall,” she adds.

The National Trust call for this income support to be removed and for there to be a transition to a new system where all public money is given only to farmers who meet higher standards of wildlife, soil, and water stewardship.

Farmers rewarded by ‘flawed and costly’ system

The last 50 years have seen a 60 percent decline in species in the UK due to loss of habitats, food sources, and breeding grounds. Soils have also been depleted and fertility impoverished.

The Trust blame much of the decline on “industrialized farming methods incentivized by successive funding regimes since the Second World War.” It is not the fault of the farmers, but of the flawed and costly system that rewards them, they add.

“Unless we make different choices,” says Ghosh, “we will leave an environment that is less productive, less rich, and less beautiful than that which we inherited.”

The Trust is of the view that in the long term, ability to grow food and look after the land for nature present no conflict – the first depends entirely on the second.

“Farmers are key partners in finding solutions but this is too important to leave to governments and farmers to sort out between themselves,” says Ghosh, drawing attention to six principles the National Trust believes should govern how public money is allocated to farming.

Proposal angers farming lobby

While the National Trust’s proposal echoes many of the ideals of other environmental and conservation groups, such as the RSPB, it has provoked an angry response from the farming lobby.

Meurig Raymond, president of the National Farmers Union (NFU), says: “The picture the National Trust is trying to paint – that of a damaged countryside – is one that neither I nor most farmers, or visitors to the countryside, will recognize.”

“Farmers have planted or restored 30,000 km of hedgerows, for example, and have increased the number of nectar and pollen rich areas by 134 percent in the past 2 years.”

He says the UK should not do anything that undermines farmers’ ability to produce food and keep British farming competitive, and adds:

“To do so would risk exporting food production out of Britain and for Britain to be a nation which relies even further on imports to feed itself.”

The NFU consider food security “a legitimate political goal and public good,” says Raymond, adding, “All our survey work shows that the British public wants to buy more British food and, interestingly, survey work also shows the British public believes farmers play a beneficial role in improving the environment at the same time.”