When the Stradivari family created the world’s best-sounding violins because of their longer, f-shaped sound holes and thicker back plates, they did so by accident and not intentionally, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) found.

Their study has been published in the academic journal Proceedings of the Royal Society: A (citation below).

Some of the best-sounding violins in the world were made by craftsmen in the Italian workshops of the Stradivari, Amati and Guarneri families in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Their violins, which today are worth millions of dollars, were made during the Cremonese period, the golden age of violin-making.

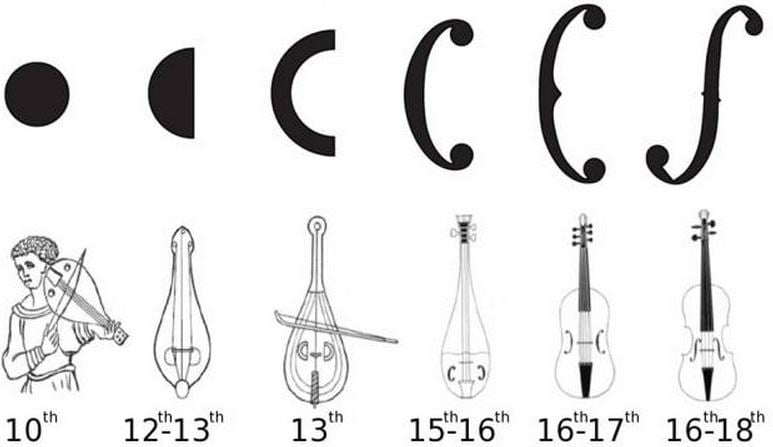

Over 8 centuries, the instrument holes evolved from the simple circle to the violin’s f-shape. (Image: MIT)

Violin-makers at the North Bennet Street School in Boston, along with fluid dynamicists and acousticians at MIT, analyzed measurements from hundreds of violins made during the Cremonese era. Their aim was to identify they key design features that gave the instruments their acoustic power, or fullness of sound.

F-hole shape gave violins their loud sound

The team found that what gave the violins their sound was the length and shape of their “f-holes”, through which air escapes. The more elongated these holes are, the more sound a violin can produce.

Furthermore, an extended sound hole does not take up much violin space, while still producing a full sound. The researchers found this feature was more power-efficient than the rounder sound hole of earlier instruments, such as medieval rebecs, lyres and fiddles.

A violin’s acoustic power is also boosted by the thickness of its back plate. A violin that is carved from wood is relatively elastic – as it produces sound, its body may respond to air vibrations, expanding and contracting minutely. They found that a thicker back plate boosted a violin’s sound.

Nicholas Makris, a professor of mechanical and ocean engineering at MIT, and colleagues found that as violins were created initially by Amati, then Stradivari and finally Guarneri, the f-holes gradually became more elongated and the back plates thicker.

Were the new violin designs deliberate?

The team set out to determine whether these three violin-making families intentionally changed the designs of their instruments to get a more powerful sound.

They worked the measurements from hundreds of violins made during the Cremonese era into an evolutionary mode. They found that any change in design was due to craftsmanship error, what they referred to as “natural mutation”.

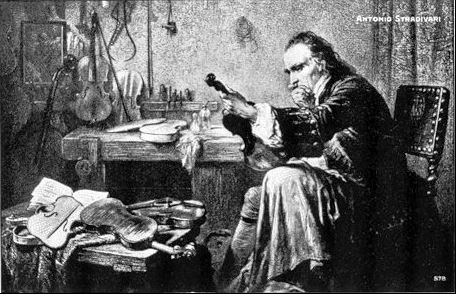

Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) improved the quality of sound of the violins he created probably by accident. (Image: Wikipedia)

In other words, the development of thicker back plates and longer sound holes occurred by accident.

“We found that if you try to replicate a sound hole exactly from the last one you made, you’ll always have a little error.”

“You’re cutting with a knife into thin wood and you can’t get it perfectly, and the error we report is about 2 percent … always within what would have happened if it was an evolutionary change, accidentally from random fluctuations.”

While acknowledging that each violin-maker undoubtedly possessed a good ear – in order to identify and replicate the best-sounding violins – whether they associated the particular design features with a more powerful sound is still up for debate, the researchers said.

Prof. Makris said:

“People had to be listening, and had to be picking things that were more efficient, and were making good selection of what instrument to replicate. Whether they understood, ‘Oh, we need to make [the sound hole] more slender,’ we can’t say. But they definitely knew what was a better instrument to replicate.”

Professor Nicholas Makris is Director of the Laboratory for Undersea Remote Sensing at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Image: MIT)

Curiosity started after Markris took up playing the lute

Prof. Makris, whose work is primarily in ocean exploration with acoustics, took up playing the lute about ten years ago and promised himself that he would not think about the acoustics of the instruments. “I’m just going to play the thing,” he remembers.

That pledge did not last long. In time, after talking with lutemakers and players in an effort to understand the instrument, which once was Europe’s most popular, his interest in its acoustics grew.

The violin is much louder than the lute. The lute’s sound holes are round rather than f-shaped, it also has elaborate interior carvings (rosettes), inherited from the oud, its Middle Eastern ancestor.

Some years ago, a well-known lute player asked Prof. Makris whether the carvings within a lute’s sound hole affected the overall sound it produced.

Prof. Makris realized that the frequencies of sound from a lute were in the range where the airflow through the circular sound hole behaved nearly as incompressible fluid, and asked Yuming Liu, a principal research scientist at the Department of Mechanical Engineering at MIT to help him find out.

The researchers modeled the airflow through a simple round hole, and also through a more elaborately patterned hole with the same diameter. In both cases, they found that the air flowed fastest at the periphery of the hole. The interior of the hole, whether partially filled or open, did not affect airflow significantly.

A study spanning 8 centuries

Attempting to answer the lute player’s simple question turned into a seven-year project in which the team examined the acoustic dynamics through time of several instruments, from the Middle Eastern oud, to medieval fiddles, the guitar, and ultimately the violin – a period spanning from the 10th to 18th centuries.

Roman Barnas, director of violinmaking and repair at the North Bennet Street School, an expert on the construction of early instruments, urged the researchers to include analysis of the violin.

Throughout the eight-century period, the team noted an evolution in the sound-hole shape – from a plain round hole to a semicircle, which eventually became a c-shape that gradually got longer, and ultimately assumed the f-shape of the violin. While the interior void of these shapes gradually became smaller, their perimeters steadily grew.

As with the evolution of the f-hole’s shape during the Cremonese era, the researchers found that the overall shape of the earlier instruments evolved to be more powerful and more acoustically efficient – though this was not necessarily done deliberately.

Prof. Makris said:

“We think these changes are still within the possibility of natural mutation. All of these subtle parameters of shape, we’ve modeled, and are able to make very good predictions on what the effects will be on frequency and power.”

Prof. Makris believes the study findings may help master violin-makers today who are seeking to create fuller-sounding instruments. He acknowledges, however, that there is more to making a quality violin than adjusting a few parameters.

Prof. Makris said:

“Mystery is good, and there’s magic in violinmaking,” Makris says. “Some makers, I don’t know how they do it – it’s an art form. They have their techniques and methods. But here, for us, it’s good to understand scientifically as much as you can.”

The study was partly funded by the Office of Naval Research.

Citation: “The evolution of air resonance power efficiency in the violin and its ancestors,” Hadi T. Nia, Ankita D. Jain, Yuming Liu, Mohammad-Reza Alam, Roman Barnas, Nicholas C. Makris. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: 2015 471 20140905; DOI: 10.1098/rspa.2014.0905. Published 11 Februar,y 2015.