Warfare existed ten thousand years ago, during the late Stone Age among hunter-gatherers, a study has found, after skeletal remains of a group of foragers were unearthed in Kenya. University of Cambridge scientists saw evidence of a violent encounter between clashing groups.

This latest finding backs the arguments of experts who say warfare is in our nature, rather than something we acquired after we started to own things, especially land.

The prehistoric bones were unearthed 30 km (18.6 m) west of Lake Turkana in Kenya, at a place called Nataruk.

The skeleton of an adult male lying prone in lagoon sediments with multiple lesions to the skull. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

The skeleton of an adult male lying prone in lagoon sediments with multiple lesions to the skull. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

Adults and children had been violently killed

The archaeologists, from Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies (LCHES) at the University of Cambridge, found partial remains of twenty-seven prehistoric humans, including at least eight adult females and six children.

Dr. Marta Mirazón Lahr and colleagues published details of their study and findings in the academic journal Nature.

Twelve skeletons were relatively intact, and of these, ten showed clear signs of a violent death, including extreme blunt-force trauma to cheekbones and crania (skulls), ribs, knees, broken hands, and arrow lesions to the neck.

They also found stone projectile tips lodged into the thorax and skull of two adult males. Many of the skeletons were discovered faced down – most of them had severe cranial fractures.

Among the in situ skeletal remains, at least five individuals had evidence of ‘sharp-force trauma’. The researchers believe some of them had arrow wounds.

Some of the individuals had been tied up

Four of them were found in a position suggesting that their hands had been tied up, including a heavily-pregnant woman. Foetal (US: fetal) bones were uncovered.

The skeleton of this man has skull and neck vertebrae lesions, which suggest he was attacked with clubs and arrows. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

The skeleton of this man has skull and neck vertebrae lesions, which suggest he was attacked with clubs and arrows. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

The dead bodies had not been buried. Some had fallen into a lagoon that has long since dried up – the bones were preserved in sediment.

Evidence suggests that these hunter-gatherers, possibly members of an extended family, were attacked and killed by a rival group of Stone Age foragers.

Dr. Mirazón Lahr and colleagues believe what they found is the earliest scientifically-dated historical evidence of human conflict – an ancient prelude to what we call warfare.

Is organised warfare in our nature or was it acquired?

Historians, anthropologists and others have long argued about the origins of warfare. Is our capacity for organized violence part of an evolutionary trait that has existed in our species for a very long time, or is it a symptom of the concept of ownership that appeared when we became farmers and started owning land?

This skeleton of a woman was found reclining on her left elbow with fractures on her knees. The position of her hands suggests they may have been bound. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

This skeleton of a woman was found reclining on her left elbow with fractures on her knees. The position of her hands suggests they may have been bound. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

In other words, is warfare in our genes, or did we learn to become the way we are?

The ‘Nataruk Massacre’ is the earliest record of violence between rival groups among prehistoric hunter-gatherers who were predominantly nomadic. The only similar evidence, unearthed in Sudan in the 1960s, is undated, although it is frequently quoted as of similar age.

The finding in Sudan consists of cemetery burials, which points to a settled (non-nomadic) lifestyle.

Dr. Mirazón Lahr said:

“The deaths at Nataruk are testimony to the antiquity of inter-group violence and war. These human remains record the intentional killing of a small band of foragers with no deliberate burial, and provide unique evidence that warfare was part of the repertoire of inter-group relations among some prehistoric hunter-gatherers.”

The site was discovered in 2012. After carefully removing the skeletons, the scientists used radiocarbon and other dating techniques. Other samples of shell and sediment were also carbon dated, in order to place Nataruk in time.

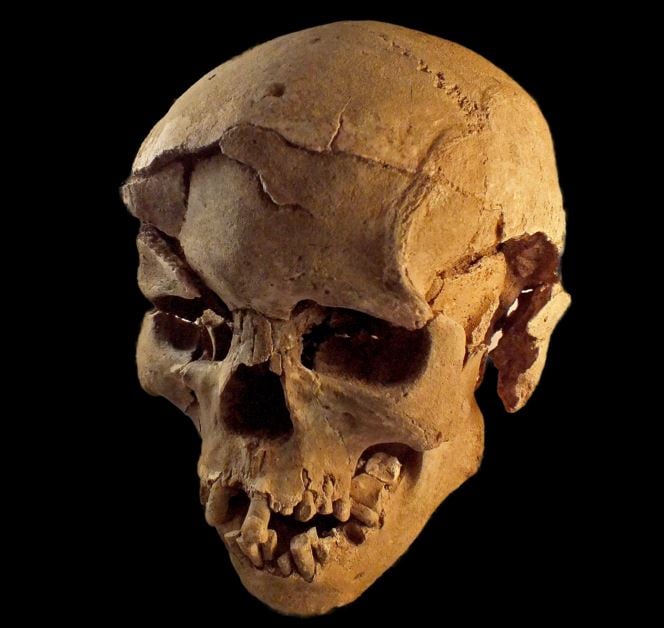

A human skull with multiple lesions on front and left side, consistent with wounds from a blunt implement. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

A human skull with multiple lesions on front and left side, consistent with wounds from a blunt implement. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

Human warfare is at least 10,000 years old

The authors estimate that the violent event occurred between 9,500 and 10,500 years ago, around the beginning of the Holocene – the geological epoch that came immediately after the last Ice Age.

Today, the area around Nataruk is scrubland. Ten thousand years ago it was a fertile lakeshore that sustained a large population of hunter-gatherers.

The site would have been on the edge of a lagoon near the shores of the much bigger Lake Turkana, probably covered in marshland and bordered by wooded corridors and forest.

This lagoon-side spot was probably an ideal place for prehistoric hunter-gatherers to inhabit, with easy access to fishing and drinking water. Most likely, many other groups of humans also coveted it.

The researchers found several artefacts at the site, including pottery, suggesting that foraged food was stored.

The skeleton of a pregnant woman was found in this unusual sitting position, which suggests that both her hands and feet had probably been bound. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

The skeleton of a pregnant woman was found in this unusual sitting position, which suggests that both her hands and feet had probably been bound. (Image: cam.ac.uk)

Were they fighting for food, territory, or women & children?

Dr. Mirazón Lahr said:

“The Nataruk massacre may have resulted from an attempt to seize resources – territory, women, children, food stored in pots – whose value was similar to those of later food-producing agricultural societies, among whom violent attacks on settlements became part of life.”

“This would extend the history of the same underlying socio-economic conditions that characterise other instances of early warfare: a more settled, materially richer way of life. However, Nataruk may simply be evidence of a standard antagonistic response to an encounter between two social groups at that time.”

In recent history, fighting between hunter-gatherer groups typically resulted in the men being killed, while the women and children were subsumed into the victors’ group.

The Nataruk Massacre was different. Of the twenty-seven humans recorded, twenty-one were adults, eight males, eight females, and five undefined. Partial remains of six children were found amongst the remains of four adult females, and bone fragments of adults of unknown sex. No children were found anywhere near the men.

Obsidian bladelets, either the tips of spears or arrows, were found within the skeletal remains. (Image: nature.com)

Obsidian bladelets, either the tips of spears or arrows, were found within the skeletal remains. (Image: nature.com)

All but one of the juvenile remains are of children under six years of age. The exception was a young teenager, aged between 12 and 15 years (dentally), but whose bones were clearly small for his or her age.

Evidence of attacks with clubs, spears and maybe arrows

Ten skeletons have evidence of serious lesions that were probably immediately lethal. As well as five – maybe six – cases of arrow wound-like trauma, five cases of extreme blunt-force to the skull can be seen, perhaps caused by a wooden club. Other recorded traumas include fractured ribs, hands and knees.

Within two of the bodies, three artefacts were found – probably the remains of spear or arrow tips. Two of them were made from obsidian: a black, volcanic rock that is easily worked to razor-like sharpness.

Dr. Mirazón Lahr said:

“Obsidian is rare in other late Stone Age sites of this area in West Turkana, which may suggest that the two groups confronted at Nataruk had different home ranges.”

One of the male skeletons had an obsidian ‘bladelet’ still stuck in his skull. It did not break through the bone, but another lesion suggests that a second weapon did, crushing the whole of the right-front part of his head and face.

Dr. Mirazón Lahr said:

“The man appears to have been hit in the head by at least two projectiles and in the knees by a blunt instrument, falling face down into the lagoon’s shallow water.”

Another adult man received two blows to the head – one on the left side of his skull and another above his right eye. The two blows crushed his skull at the point of impact, causing it to crack in several different directions.

Pregnant woman had probably been bound

The remains of a 6-to-9 month old foetus were recovered from within the abdominal cavity of one of the females, who was discovered in an unusual sitting position. When they first found her, all Dr. Mirazón Lahr and colleagues could see were her broken knees protruding from the earth.

From the position of the body, the authors believe the woman’s hands and feet had been bound.

The Nataruk skeletons are now housed at the Turkana Basin Institute, Turkwell Station, for the National Museums of Kenya.

Nobody today knows why these people were killed so violently. The site is one of the clearest cases of inter-group violence among prehistoric foragers, says Dr. Mirazón Lahr, and evidence that small-scale warfare existed among foraging societies.

Study co-author, Professor Robert Foley, also from Cambridge’s LCHES, sees the findings at Nataruk as evidence of how ancient human violence is, as is the altruism that made us the most cooperative species on Earth.

Prof. Foley said:

“I’ve no doubt it is in our biology to be aggressive and lethal, just as it is to be deeply caring and loving.”

“A lot of what we understand about human evolutionary biology suggests these are two sides of the same coin.”

Citation: “Inter-group violence among early Holocene hunter-gatherers of West Turkana, Kenya,” M. Mirazón Lahr, R. Grün, F. Rivera, R. K. Power, A. Mounier, B. Copsey, D. M. Mukhongo, F. Crivellaro, J. E. Edung, J. M. Maillo Fernandez, C. Kiarie,A. Leakey, J. Lawrence, E. Mbua, H. Miller, A. Muigai, A. Van Baelen, R. Wood, J.-L. Schwenninger, H. Achyuthan, A. Wilshaw and R. A. Foley. Nature 529, 394–398. Published 21 January 2016. DOI: 10.1038/nature16477.

Video – Nataruk: Evidence of a preshistoric massacre

In this Cambridge University video, researchers discuss their findings, and what they mean for the history of inter-group violence between humans.