Microscopic grains of rock detected on the surface of one of Saturn’s sixty-two moons, Enceladus, suggest the presence of warm water, which in turn raises the likelihood of there being life as we know it, says a team of Cassini mission scientists led by the University of Colorado Boulder.

The scientists, who published their findings in the academic journal Nature (citation below), say the grains are the first clear evidence of an icy moon with hydrothermal activity (activity with heated water), in which seawater infiltrates and reacts with a rocky crust, resulting as a warm, mineral-laden solution.

Lead author, Sean Hsu, Research Associate at CU-Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP), and colleagues say the finding increases the prospect that Enceladus might contain environments suitable for living organisms.

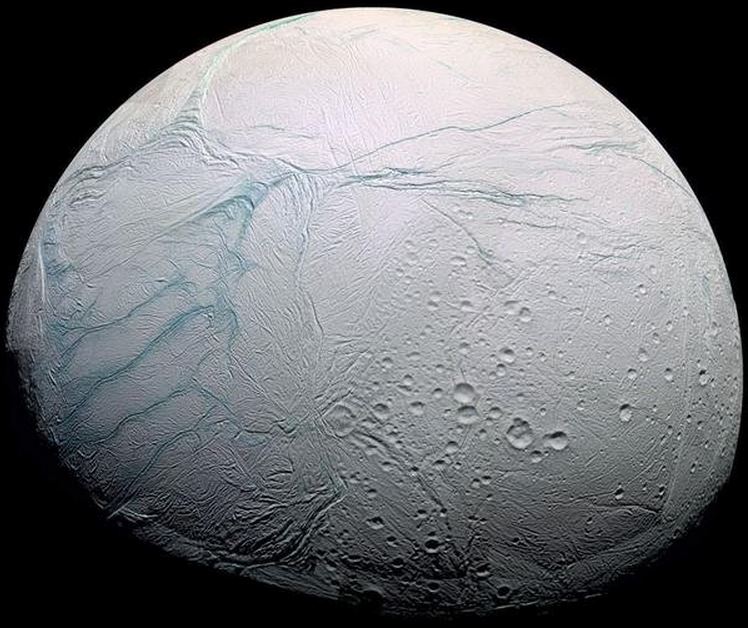

Enceladus is spewing tiny silica grains, an indication hydrothermal activity is occurring in its ice-covered ocean. On Earth, such extreme environments are known to be suitable for life. (Image: University of Colorado)

The Cassini-Huygens (Cassini) spacecraft left Earth in 1997. It was sent to study the planet Saturn and its several moons. The unmanned spacecraft arrived there in 2004.

The surprising new result follows a comprehensive, four-year analysis of data from Cassini, computer simulations, and laboratory experiments.

Grains form when hot water meets cooler water

The authors believe the minuscule grains are probably formed when hot water from below the seabed containing dissolved minerals travel upward, coming into contact with the cooler water near the bottom of the sea.

For these interactions that form the tiny rock grains to occur, water temperatures would need to be at least 90°C (194°F).

Mr. Hsu said:

“It’s very exciting that we can use these tiny grains of rock, spewed into space by geysers, to tell us about conditions on – and beneath – the ocean floor of an icy moon.”

Since 2004, Cassini’s CDA (Cosmic Dust Analyzer) instrument has detected minuscule silicon-rich rock particles several times.

Through a process of elimination, the team concluded that these particles must be grains of silica, which is commonly found on Earth in sand and the mineral quartz. Most of the grains observed by Cassini were similar in size – with the larger ones measuring six to nine nanometers – suggesting they were formed through a specific process.

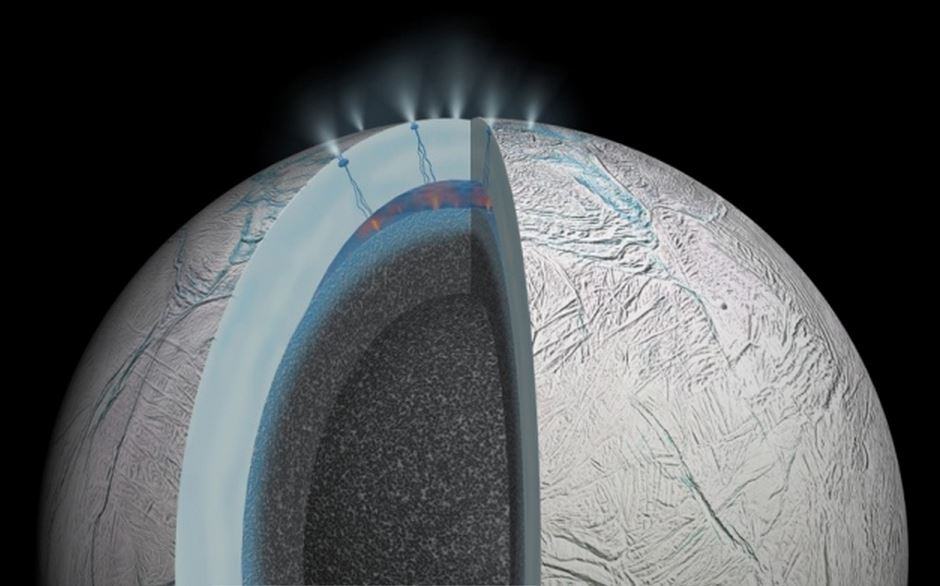

Evidence points to hot springs on the floor of Enceladus’ ocean spraying jets through its icy crust. (Image: Nature)

The most common way silica grains of this size are formed on Earth is through hydrothermal activity involving specific conditions – slightly alkaline water with modest salinity, super-saturated with silica, undergoing a significant drop in temperature.

Co-author, Frank Postberg, a CDA team scientists at Heidelberg University in Germany, said:

“We methodically searched for alternate explanations for the nano-silca grains, but every new result pointed to a single, most likely origin.”

Postberg, Hsu and colleagues at the University of Tokyo carried out the detailed lab experiments that validated the hydrothermal activity hypothesis.

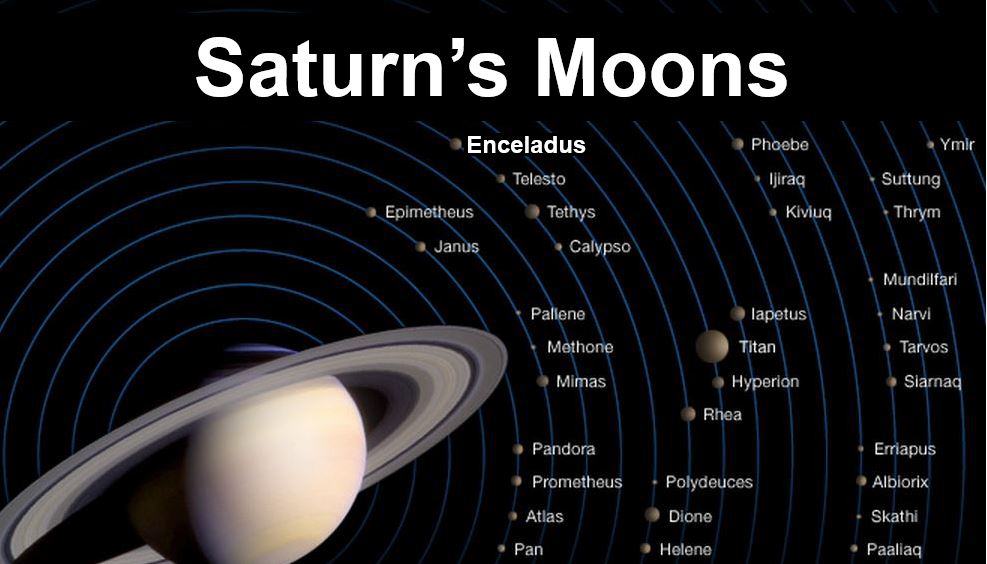

NASA says 62 moons have so far been discovered in orbits around Saturn, with 53 of them officially named. (Image: NASA)

The Japanese scientists, led by Yasuhito Sekine, confirmed the conditions under which silica grains the same size as those detected by Cassini could form. They believe these conditions could exist at Enceladus’ seafloor, where hot water from beneath meets the comparatively cold water at the ocean bottom.

Co-authors also included Assistant Professor Sascha Kempf of LASP and CU-Boulder Professor Mihaly Horanyi, who are both also faculty members in CU-Boulder’s physics department and co-investigators of the Cassini CDA.

Prof. Kempf says the puzzle of the Enceladus plumes, which were first observed not long after Cassini reached Saturn in 2004, has to some extent been solved.

“Ten years ago it was a big mystery why the nano-grains were made of silica rather than water ice. Now we know the observations were correct. We know where the silica particles are coming from, and why we are seeing them. We learned something very unexpected, which is why I really like this study,” Prof. Kempf explained.

The researchers believe the very small silica particles travel upward quite rapidly from the hydrothermal origin to the near-surface sources of the moon’s geysers.

The scientists wrote “From seafloor to outer space, a distance of about 30 miles (50 kilometers), the grains spend a few months to a few years in transit, otherwise they would grow to much larger sizes.”

Cassini first sent back data showing active geology on Enceladus in 2005, with evidence in the south polar region of an icy spray, as well as higher-than-expected temperatures in the icy surface in that region.

A towering plume

It soon became apparent that there was a towering plume of water ice and vapor, organic materials and salts that is released from relatively warm fractures on the moon’s wrinkled surface.

According to gravity measurements published in 2014, there is probably a 10-kilometer-deep (6-mile-deep) ocean beneath an ice shell about 30 to 40 kilometers (19 to 25 miles) thick.

The authors write that Cassini’s gravity measurements point to a rock core that is quite porous, which would allow its ocean water to percolate into the interior. This would provide a large surface area where water and rock could interact.

Mr. Hsu said:

“It’s possible much of this interesting hot water chemistry occurs deep inside the moon’s core.”

Citation: “Ongoing hydrothermal activities within Enceladus,” Hsiang-Wen Hsu, Frank Postberg, Yasuhito Sekine, Takazo Shibuya, Sascha Kempf, Mihály Horányi, Antal Juhász, Nicolas Altobelli, Katsuhiko Suzuki, Yuka Masaki, Tatsu Kuwatani, Shogo Tachibana, Sin-iti Sirono, Georg Moragas-Klostermeyer & Ralf Srama. Nature. Published online 11 March, 2015. DOI: 10.1038/nature14262.

Reuters Video – Hot water clue to life on Enceladus