Investing in art, is a good idea? Art investment selection bias appears to have overestimated returns and underestimated risk.

According to a new study by researchers at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, the Luxembourg School of Finance and the Erasmus School of Economics, buy paintings if you enjoy looking at them, don’t if your aim is to make money.

Art investment selection bias is when analysts only focus on paintings that have been sold and do not include the value of those not sold.

According to the media, art has become progressively more popular as an investment option for those wanting a well-diversified portfolio. Art advisors quote an annual return (average) of 10% over the last forty years.

There is no shortage of art investors. Some funds, such as The Fine Art Fund group are making it possible for people from a wide range of socioeconomic levels to enter the world of art investing.

So, with all this good news going art’s way, is it really a good investment?

The researchers presented a study earlier this year at the European Finance Association conference which showed that want-to-be art investors should be cautious.

Art investment returns have been significantly overestimated

Analysts have been overestimating the returns of fine art considerably and underestimating the risks.

According to this latest study, carried out by Arthur Korteweg, Roman Kräussl and Patrick Verwijmeren, the true return of fine art as an asset class over a nearly 40-year period (1971-2010) was approximately 6.5% per year and not 10%. They based their research on data from BASI (Blouin Art Sales Index).

They also report that “holding an art fund in your portfolio does not increase the chances that the portfolio will outperform.”

Analysts have been overestimating returns and underestimating the risks of investing in art because of art investment selection bias. Selection bias has been suggested as a cause for distorted results in other types of assets for several years. The researchers claim this study is the first to find a way to explain it.

Korteweg and colleagues analyzed data on the sales of 20,538 paintings from 1972 to 2010. They found that the Sharpe Ratio for art is not the 0.24 people had been told, but rather 0.04. Over the same period, the Sharpe Ratio on equities was higher, at 0.30.

The Sharpe ratio, developed by Nobel Laureate William Sharpe, tells you whether an asset’s returns are due to smart investment decisions or the result of taking too much of a risk. The higher the number the better its risk-adjusted performance has been.

Why has art investment selection bias occurred?

The main reason for art investment selection bias is that paintings in high demand are sold more than those in low demand. High-demand paintings go for a higher price at auctions. Owners of paintings are more likely to sell those that have increased in value the most since they bought them.

There is a similar selection bias in the housing market – those that went up in price more are more likely to go on sale.

An example of art investment selection bias

Imagine you bought two paintings – “The Ship” by Quentin Smith and “The Ploughman” by Arnold Suarez – in 1972 from a dealer for $10,000 each. Suarez’ career took off, he became famous, and you sold The Ploughman for $20,000 in 2010. Smith, on the other hand, never got anywhere in his career. Let’s say for the sake of argument that The Ship’s value stayed at $10,000. You did not sell The Ship, it is still hanging on the wall over your fireplace.

According to the art index, your investment increased in value by 100%, because it only looks at paintings sold, therefore only registers The Ploughman, which doubled in value. However, your $20,000 investment did not increase to $40,000, but only $30,000, a return of just 50% over 38 years, not 100%.

If Smith’s and Suarez’ paintings were calculated together over the 38-year period, it would be a better way of estimating returns.

Paintings that sell are not “average” paintings

The researchers found that paintings that sell are not “average” paintings – far from it – they are the ones that rise in value the most. They wrote, “To impute a more accurate value to the paintings that never sell or sell less frequently, our methodology uses what we know about how rapidly the paintings that sell have appreciated, and how often they are sold.”

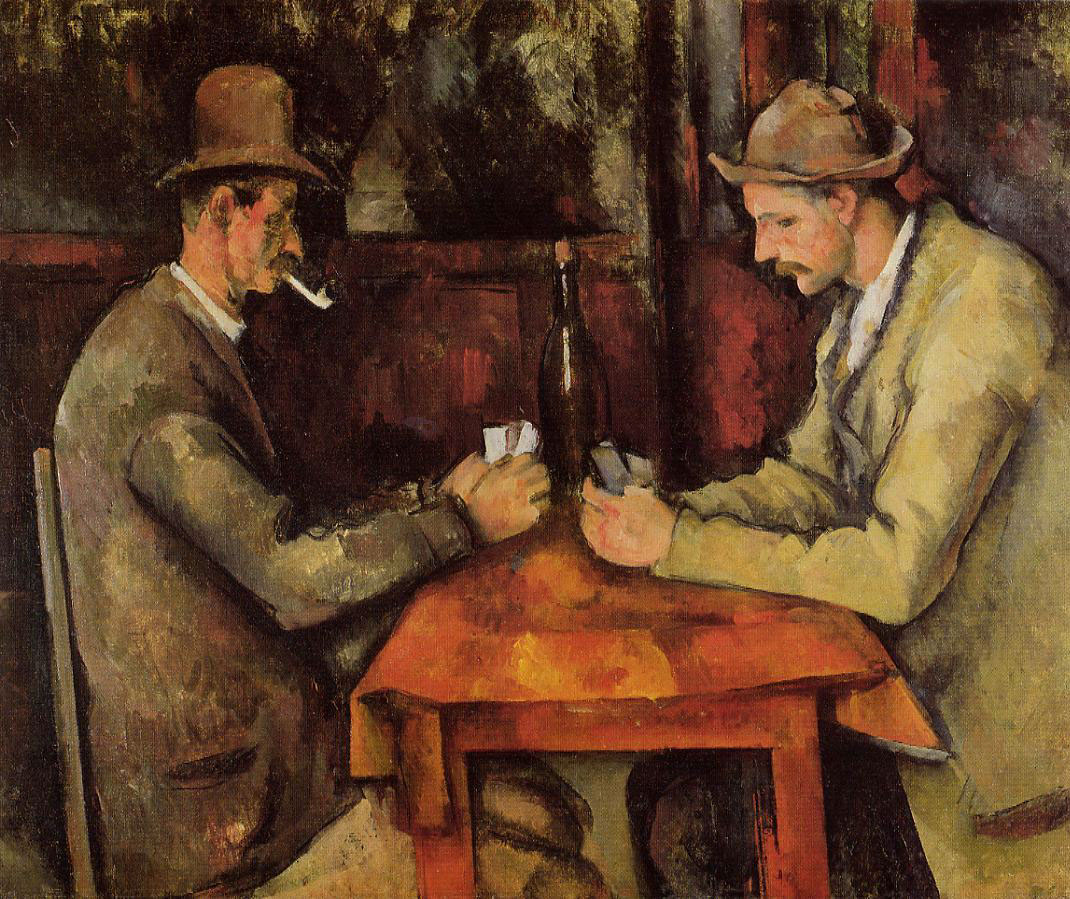

The Card Players by Paul Cézanne, which sold for more than $250 million in 2011, is not an “average” painting.

The team’s model allowed them to examine five different styles of painting, including 19th Century European, American, Old Masters, Impressionist and Modern, Contemporary and Post-War. They also looked at the ROI (return on investment) of works by top-selling artists.

As an aside, they found that:

- 2%+ of sales occurred within 2 years of an artist’s death.

- The average auction price of a painting was $61,929.

- 25% of sales took place at Sotheby’s and 22% at Christie’s.

- ⅓ of sales were Impressionist and Modern style paintings.

- ¼ were European 19th century.

- 16% were Post-War and Contemporary.

- 12% were American.

The authors wrote:

“The conclusion about art as an investment is clear: When we compared the investment returns and risk of all the styles of art to a portfolio of pure stocks, we found that art investments would not substantially improve the risk/return profile of a portfolio diversified among traditional asset classes, such as stocks and bonds.”