Clues to the autoimmune origins of lupus (systemic lupus erythematosus or LSE) are in precursor cells, say researchers. Precursor cells are stem cells that are committed to forming a specific kind of new blood cell. We also refer to precursor cells as blast cells or simply blasts.

The researchers, from Emory University, University of Alabama, Johns Hopkins University, NYU School of Medicine, University of Rochester, and the Georgia Institute of Technology, wrote about their study and findings in the journal Immunity (citation below).

Lupus is an autoimmune disease. This means that the body’s immune system produces antibodies that attack good cells as if they were harmful cells.

If we can learn more about these precursor cells, we may have a better understanding of what happens in lupus. Put simply; these precursor cells might tell us why lupus patients’ immune systems attack healthy cells.

What causes lupus is a mystery

Nobody is certain what causes lupus. Why the antibodies start attacking good tissue has been a mystery. However, recent research led by Emory University School of Medicine sheds light on what is happening. Specifically, why cells produce antibodies that attack healthy tissue.

Team leader Ignacio Sanz MD. and colleagues studied blood samples from ninety lupus patients. The researchers focused on DN2 B cells – a particular type of B cell.

Sanz is a Professor at Emory University’s Department of Medicine and an Eminent Scholar of the Georgia Research Alliance. He is also Division Director at Emory’s Division of Rheumatology.

In healthy people, DN2 B cells are relatively scarce. Among patients with lupus, on the other hand, DN2 B cell levels are significantly higher.

DN2 cell levels

Lupus patients can experience a wide range of symptoms because it is a ‘systemic disease.’ In other words, it affects the whole body. ‘Systemic’ means related to a ‘system’ rather than to a specific part.

Skin rashes, joint, pain, and fatigue, for example, are common symptoms. Some patients also have kidney problems.

Patients with severe disease or kidney problems had higher levels of DN2 cells, the authors wrote.

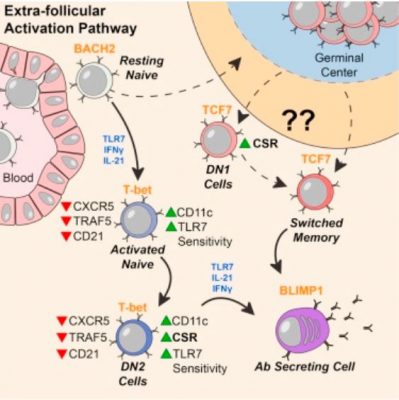

Scientists believe that DN2 B cells are ‘extra follicular.’ They are outside the B cell follicles – lymph node regions where, when there is an immune response, B cells are activated.

Co-first author, Scott Jenks, PhD, said:

“Overall, our model is that a lot of lupus auto-antibodies come from a continuous churning out of new responses. There is good evidence that DN2 cells are part of the early B cell activation pathway happening outside B cells’ normal homes in lymph nodes.”

Dr. Jenks is an Instructor of Medicine at Emory University’s School of Medicine.

Lupus rates among African Americans

A previous study at Emory showed that lupus rates were significantly higher among African American women than white women.

In this latest study, the research team noticed that DN2 cell frequency was greater in African American patients. Johns Hopkins, the University of Rochester, and Emory University recruited the participants in this study.

The research team examined DN2 cell characteristics. They also studied the patterns of genes turned on in those cells.

DN2 cells are precursor cells

It appears that DN2 cells are the precursor cells to the plasmablasts that produce autoreactive antibodies. Autoreactive antibodies are the ones that act against the organism that produced them. Autoreactive antibodies are specifically the ones that cause so much trouble for lupus patients.

During an infection, plasmablasts are an important source of antibodies that help destroy viruses and bacteria. However, in the bodies of patients with lupus, plasmablasts and B cell subsets persist in ways they shouldn’t.

In general, we can think of B cells as a library of blueprints for various antibodies/weapons, and plasmablasts as weapons factories.

We need a better understanding of where the problem plasmablasts come from; in other words, their precursor cells. These precursor cells might provide clues on how to target the plasmablasts. If we can target them, we may subsequently be able to control the disease.

TLR7 in lupus pathology

DN2 cells in lupus patients are hypersensitive to activation through TLR7, molecular probing showed. TLR7 is a pathway through which our immune system senses viral infections. Dr. Jenks believes that this may be how they get over-expanded.

Dr. Jenks said:

“Our work provides further support for the importance for TLR7 in lupus pathology. Targeting TLR7 might both block the generation of pathological B cells and prevent their subsequent activation and differentiation into plasma cells.”

In Prof. Sanz’ lab, a previous study had shown that a group of ‘activated naïve’ B cells were precursor cells to the problem plasmablasts. These activated naïve B cells are very similar to DN2 cells in their molecular markers.

Dr. Jenks says that the research team is now trying to determine what the relationship between these precursor cells is. Specifically, activated naïve cells and DN2 cells. They are also looking into additional intervention strategies that could target those cells and control them.

Citation

“Distinct Effector B Cells Induced by Unregulated Toll-like Receptor 7 Contribute to Pathogenic Responses in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus,” Scott A. Jenks, Kevin S. Cashman, Esther Zumaquero, Zoe Simon, Regina Bugrovsky, Emily L. Blalock, Christopher D. Scharer, Urko M. Marigorta, Aakash V. Patel, Xiaoqian Wang, Deepak Tomar, Matthew C. Woodruff, Jeremy M. Boss, Frances E. Lund, Ignacio Sanz, Zoe Simon, Regina Bugrovsky, Emily L. Blalock, Christopher D. Scharer, Greg Gibson, F. Eun-Hyung Lee, Christopher M. Tipton, Chungwen Wei, S. Sam Lim, Michelle Petri, Timothy B. Niewold, and Jennifer H. Anolik. Immunity (2018). Published: October 09, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.08.015.