The 90% complete fossilized skeleton of a ‘terror bird’, a prehistoric, carnivorous, flightless, fearsome creature, suggests it had a very deep voice and low-frequency hearing, say Argentinian paleontologists. It was probably the top predator in the area.

The fossil, which is missing only a few wing and toe bones and the tip of its tail, found on a beach in Argentina near the popular tourist city of Mar del Plata, is the most complete skeleton ever discovered of a terror bird, known scientifically as Phorusrhacidae.

The specimen was so well preserved that the researchers were even able to reconstruct the shape of its inner ear, which indicates it had low-frequency hearing, and consequently a very deep voice.

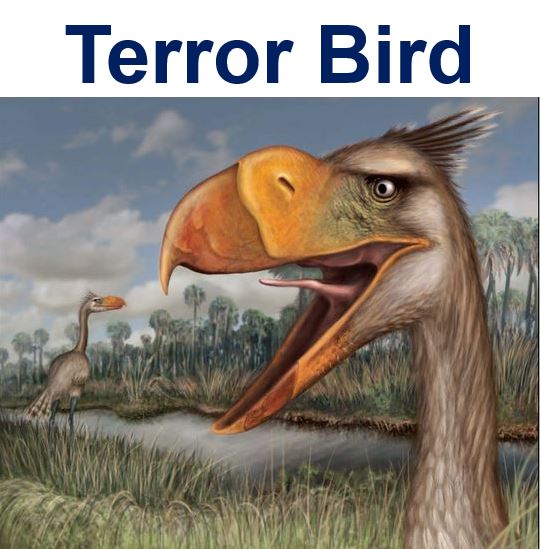

The new fossil find provided insight into the Terror Bird’s voice and sense of hearing. (Image: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology)

Federico Degrange, a terror bird specialist from the from the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba in Argentina, and colleagues wrote about their find in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (citation below).

Dr. Degrange explained to the BBC how the tide presented a challenge when excavating the fossil:

“The sea can actually take the fossil and destroy it in the sea. It’s a nice place to work, but you have to be fast.”

Top predators in the area

Following the extinction of the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago, terror birds (phorusrhacids) were the top predators in the South American land mass.

The fearsome birds stood up to 10 feet (3 meters) tall, had long legs and powerful hooked beaks. According to a previous study, the bird would strike its prey with a single blow and then eat it.

Dr. Degrange said:

“They evolved very unique forms, with huge skulls, huge beaks with hooks, and long hind limbs. They lost their ability to fly and they developed very unusual predatory capabilities that were not present in any comparable animals.”

The specimen, which is in fact a newly-discovered species, has been called Llallawavis scagliali, after Fernando Scaglia, the study’s senior author.

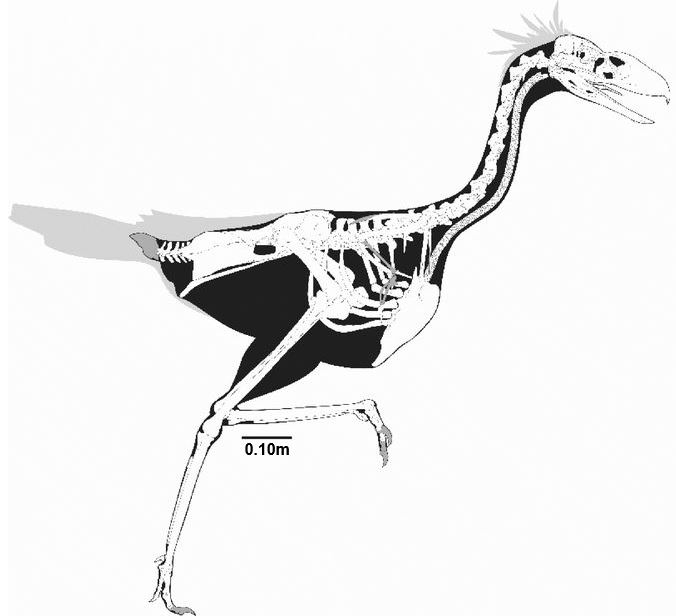

When the recovered specimen was alive, the researchers say it weighed about 18 kg (39.7 lbs) and stood about 1.2 meters (47.2 inches) tall, making it a medium-sized member of the terror bird family. It lived about 3.5 million years ago, which was towards the end of the terror bird family’s period of dominance.

The research team believes L. scagliai probably lived in an open environment, maybe a grassland or a sparse forest through which small rivers flowed.

Unusual skull for a bird

Dr. Degrange believes it ate mammals and other birds probably smaller than itself. Unlike most types of birds, many of the joints between the bones in L. scagliai’s skull are fused.

The joints in its upper palate, as well as some of those near its beak, are much less flexible than they are in other birds, which may have helped it pummel its prey and more effectively tear apart carcasses.

Skeletal anatomy of L. scagliai. Bones colored in gray are missing. (Image: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology)

As this specimen’s skull was so well preserved, Dr. Degrange and colleagues were able to make some educated guesses about the bird’s sensory capabilities, and even its voice. “A very interesting thing is that we could reconstruct the shape of the inner ear,” he said.

It was probably sensitive to very low frequency sounds, the authors wrote, and likely communicated at low frequencies too.

The authors concluded in an Abstract in the journal:

“The discovery of this new species provides new insights for studying the anatomy and phylogeny of phorusrhacids and a better understanding of this group’s diversification.”

Citation: “A new Mesembriornithinae (Aves, Phorusrhacidae) provides new insights into the phylogeny and sensory capabilities of terror birds,” Federico J. Degrange, Claudia P. Tambussi, Matías L. Taglioretti, Alejandro Dondas & Fernando Scaglia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Published 20 March, 2015. DOI:10.1080/02724634.2014.912656.