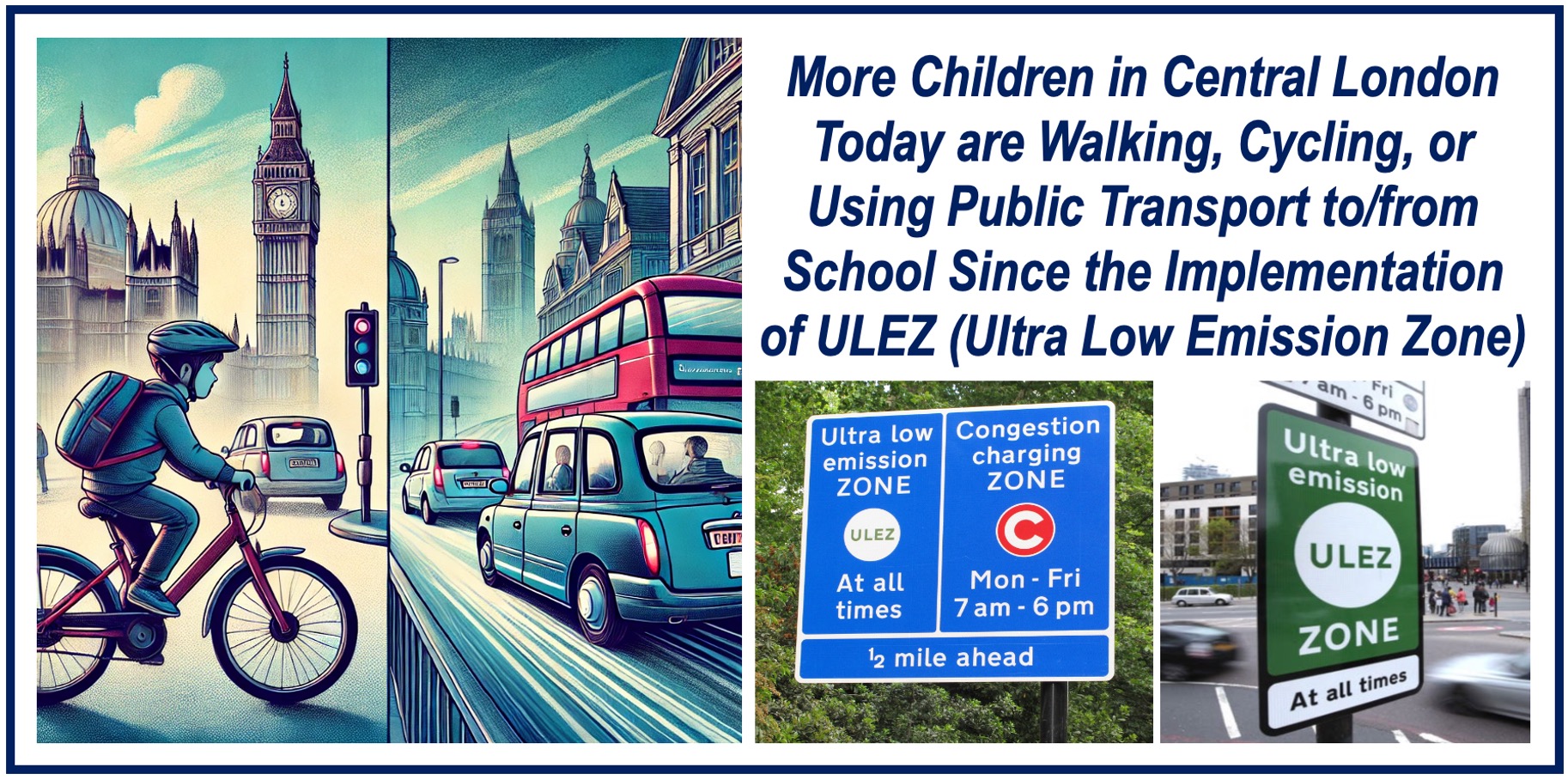

Forty percent of children who travelled to school by car in central London switched to walking, cycling, or public transport after ULEZ (Ultra-Low Emission Zone) was introduced, a new study reports.

In Luton, a comparison area with no ULEZ, just 20% of children switched from commuting by car to more active modes of transport during the same period.

Car travel and air pollution

Car travel adds to air pollution, which plays a significant role in heart and lung diseases, including triggering asthma attacks. Additionally, it reduces children’s chances for physical activity, which can negatively affect their development and mental well-being while also raising the risk of obesity and chronic health conditions.

UK guidelines recommend a daily average of 60 minutes of moderate-to vigorous physically activity for children of school age and adolescents. However, only 45% of five- to sixteen-year-olds met these levels in 2021. In the UK, one in three ten- and eleven-year-olds are overweight or obese.

ULEZ reduced air pollution levels

London introduced ULEZ in April 2019 to reduce the number of cars on the road that did not meet emission standards and improve air quality. The measure reduced harmful nitrogen oxides and particulate matter in central London by 35% and 15%, respectively, within the first ten months of its introduction.

In a study released on 5th September in the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (citation below), researchers from the University of Cambridge and Queen Mary University of London, and other institutions investigated the impact of the ULEZ on children’s school commute. This research is part of the Children’s Health in London and Luton (CHILL) study.

Image created by Market Business News.

The Study

The researchers gathered and examined data from almost 2,000 six- to nine-year-olds attending 84 primary school in London and Luton (the control area). A total of forty-four schools were located with catchment areas either within or bordering London’ ULEZ.

These school were compared to a similar number of primary schools in Luton and Dunstable (acting as a comparison group). Including the comparison site allowed the researchers to draw stronger conclusions and provided greater confidence that the observed changes were due to the introduction of the ULEZ.

The research team collected data from June 2018 to April 2019, before ULEZ was implemented, and again from June 2019 to March 2020, a year after its implementation. The second data collection period took place before COVID-19-related school closures.

-

Central London vs. Comparison Group

Among schoolchildren in London who commuted by car before the introduction of ULEZ, 42% switched to more active modes of transport, while 5% switched in the opposite direction, from active to inactive modes.

In contrast, only 20% of children in Luton shifted from car travel to active modes, while a nearly identical proportion (21%) switched from active to car travel. This indicates that children in London’s ULEZ were 3.6 times more likely to transition from car travel to active modes than those in Luton, and significantly less likely (0.11 times) to switch to inactive modes.

The ULEZ had the greatest effect on encouraging active travel for children who lived more than half a mile (0.78 km) from school. This is likely because many children living closer to school were already walking or cycling before the ULEZ was implemented, so there was more room for change among those living farther away.

-

Authors’ Comments

First author of the published study, Dr Christina Xiao, from the Medical Research Council (MRC) Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge, said:

“The introduction of the ULEZ was associated with positive changes in how children travelled to school, with a much larger number of children moving from inactive to active modes of transport in London than in Luton.”

“Given children’s heightened vulnerability to air pollution and the critical role of physical activity for their health and development, financial disincentives for car use could encourage healthier travel habits among this young population, even if they do not necessarily target them.”

Dr Jenna Panter from the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, joint senior author, said:

“The previous government was committed to increasing the share of children walking to school by 2025 and we hope the new government will follow suit.”

“Changing the way children travel to school can have significant effects on their levels of physical activity at the same time as bringing other co-benefits like improving congestion and air quality, as about a quarter of car trips during peak morning hours in London are made for school drop-offs.”

-

Impact of ULEZ on Vehicle Numbers

The total number of vehicles on the road in central London declined by 9% after ULEZ was introduced, with a 34% reduction in vehicles that failed to meet the required exhaust emission standard. Importantly, there was no compelling evidence that traffic had simply shifted to nearby areas.

Professor Chris Griffiths from the Wolfson Institute of Population Health at Queen Mary University of London, joint senior author, said:

“Establishing healthy habits early is critical to healthy adulthood and the prevention of disabling long term illness, especially obesity and the crippling diseases associated with it. The robust design of our study, with Luton as a comparator area, strongly suggests the ULEZ is driving this switch to active travel.”

“This is evidence that Clean Air Zone intervention programs aimed at reducing air pollution have the potential to also improve overall public health by addressing key factors that contribute to illness.”

-

COVID-19

The study was paused during 2020 and 2021 due to COVID-19 restrictions, which took effect in late March 2020. However, since both London and Luton, the study areas, were similarly impacted by the pandemic, the researchers believe this disruption is unlikely to have influenced the results.

The study has now resumed, allowing the researchers to follow up with the children and assess the longer-term effects of the ULEZ, including whether the changes observed in the first year have continued over time.

The following institutions collaborated on the study: the University of Cambridge, Imperial College, Queen Mary University of London, University of Edinburgh, University of Bedfordshire, University of Oxford, and University of Southern California. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research (NIHR), NIHR Applied Research Collaboration North Thames, and the Cambridge Trust.

The information in this article is based on research findings published by the University of Cambridge.

Citation:

Xiao, C et al. Children’s Health in London and Luton (CHILL) cohort: A 12-month natural experimental study of the effects of the Ultra Low Emission Zone on children’s travel to school. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity; 5 Sept 2024; DOI: 10.1186/s12966-024-01621-7