Clothing and paint colours that never fade, using the structure that birds have in their feathers to create multi-coloured plumage, could probably be used commercially, say scientists from the University of Sheffield in England, the Institut Laue-Langevin in France, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France, the Diamond Light Source in England, and the Natural History Museum in London.

Birds generate their own unique colour using structure, rather than pigments and dyes. The jay, for example, can change the colour of its feathers along the equivalent of one strand of human hair using tuneable nanostructure.

Dr Andrew Parnell, who works at the University of Sheffield’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, and colleagues said their discovery will likely lead to synthetic structural colours that could be made ultra-cheaply and used in clothes and paints – these colours, unlike pigments and dyes, would never fade.

a) A jay’s feather, whose colours are determined by the size of tiny holes. b) A Eurasian Jay (Garrulus glandarius). c) A transverse cross-section of the light-blue part of a Jay’s feather barb. d) & e) Optical microscopy images of the light-blue region – the boundaries of these cells are ordinarily visible under reflected light. (Image: www.nature.com. Credit: Luc Viatour for image (b))

a) A jay’s feather, whose colours are determined by the size of tiny holes. b) A Eurasian Jay (Garrulus glandarius). c) A transverse cross-section of the light-blue part of a Jay’s feather barb. d) & e) Optical microscopy images of the light-blue region – the boundaries of these cells are ordinarily visible under reflected light. (Image: www.nature.com. Credit: Luc Viatour for image (b))

The scientists wrote about their study and discovery in the academic journal Nature Scientific Reports.

They used X-ray scattering at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in France to examine white and blue feathers of the jay.

Birds control their feather colours in a remarkable way

They found that birds demonstrate a remarkable level of control and sophistication in producing colours.

Rather than simply using pigments and dyes that over time would fade, the birds use finely-controlled changes to the nanostructure to create their brightly-coloured feathers – which the researchers believe jays, for example, use to recognise one another.

The jay is able to pattern a range of colours along an individual feather barb – like having several different colours along just one strand of human hair.

The jay’s feather, which goes from ultra-violet through to blue and into white, consists of a nanostructured spongy keratin material – exactly the same type of material our fingernails and hair are made from.

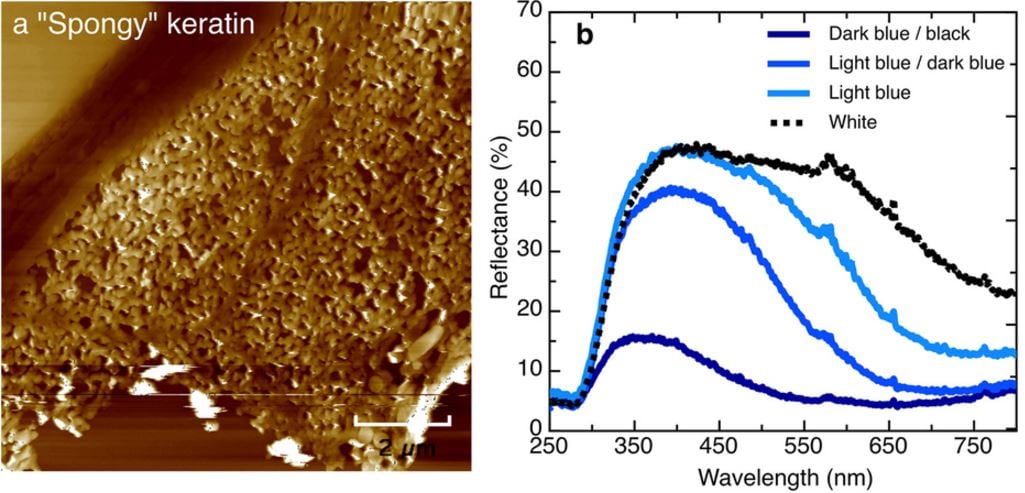

a) Scanning probe imaging showing the ‘sponge’ morphology in a Jay’s feather, responsible for the optical properties. b) The measured reflectance for the different regions of a Jay feather covert. (Image: www.nature.com)

a) Scanning probe imaging showing the ‘sponge’ morphology in a Jay’s feather, responsible for the optical properties. b) The measured reflectance for the different regions of a Jay feather covert. (Image: www.nature.com)

Tiny holes determine colours of feathers

The scientists discovered that the jay can demonstrate incredible control over the size of the holes in this spongy structure and fix them at very specific sizes, which determine the colour that is seen reflected from the feather.

When light hits a feather it scatters – how it scatters is determined by the size of the hole, and consequently the colour that is reflected.

The bigger the hole the broader the wavelength reflectance of light is, which creates the colour white. On the other hand, a smaller and more compact structure results in the colour blue.

If pigments from the birds were used to create the colours, the feathers’ colours would eventually fade.

Some birds have spectacular colours. None of them are due to dyes or pigments. They depend on how large or small the tiny holes within the feathers that light reflects through are.

Some birds have spectacular colours. None of them are due to dyes or pigments. They depend on how large or small the tiny holes within the feathers that light reflects through are.

Birds never go grey, unlike mammals with hair

However, nature has created a permanent colouring system for birds using structural changes. This is why birds, unlike humans, dogs, and other mammals which rely on pigments to colour hair, never go grey as they get older.

We go grey because pigment production declines as we age.

Dr. Parnell said:

“Conventional thought was that to control light using materials in this way we would need ultra-precise and controlled structures with many different processing stages, but if nature can assemble this material ‘on the wing’, then we should be able to do it synthetically too.”

“This discovery means that in the future, we could create long-lasting coloured coatings and materials synthetically. We have discovered it is the way in which it is formed and the control of this evolving nanostructure – by adjusting the size and density of the holes in the spongy like structure – that determines what colour is reflected.”

As we get older, the pigment cells in our hair follicles gradually die. The hair produces less pigment. Birds don’t use pigment for feather colouring, mammals do for their hair.

As we get older, the pigment cells in our hair follicles gradually die. The hair produces less pigment. Birds don’t use pigment for feather colouring, mammals do for their hair.

“Current technology cannot make colour with this level of control and precision – we still use dyes and pigments. Now we’ve learnt how nature accomplishes it, we can start to develop new materials such as clothes or paints using these nanostructuring approaches. It would potentially mean that if we created a red jumper using this method, it would retain its colour and never fade in the wash.”

Dr. Daragh McLoughlin, of the AkzoNobel Decorative Paints Material Science Research Team, explained:

“At AkzoNobel, the makers of Dulux paint, we aim to encourage and stimulate the innovation of more sustainable products that have eco-premium benefits. This exciting new insight may help us to find new ways of making paints that stay brighter and fresher-looking for longer, while also having a lower carbon footprint.”

In this study, the researchers used feathers selected from the vast collection at the Natural History Museum in London.

Dr. Adam Washington, from the University of Sheffield, said the study explained some long-standing questions regarding some colours:

“The research also answers the longstanding conundrum of why non-iridescent structural greens are rare in nature. This is because to create the colour green, a very complex and narrow wavelength is needed, something that is hard to produce by manipulating this tuneable spongy structures.”

“As a result, nature’s way to get round this and create the colour green – an obvious camouflage colour – is to mix the structural blue like that of the jay with a yellow pigment that absorbs some of the blue colour.”

Citation: “Spatially modulated structural colour in bird feathers,” Andrew J. Parnell, Andrew R. Parker, Adam L. Washington, Oleksandr O. Mykhaylyk, J. Patrick. A. Fairclough, Christopher J. Hill, Antonino Bianco, Richard A. L. Jones, Stephanie L. Burg, Andrew J. C. Dennison, Mary Snape, David M. Whittaker, Ashley J. Cadby, Andrew Smith & Sylvain Prevost. Nature Scientific Reports 5, Article number: 18317. December, 21, 2015. DOI: doi:10.1038/srep18317.