An Anglo-Saxon island that was a settlement where people lived at least 1200 years ago has been discovered by a team of archaeologists from the University of Sheffield at Little Carlton near Louth in Lincolnshire.

The island, which was home to a Middle Saxon settlement, probably has plenty more exciting remains waiting to be discovered. The archaeologists believe that their work so far is only the tip of a huge iceberg underneath. Experts think the site was a previously unknown trading or monastic centre.

The Middle Anglo-Saxon period spanned from 600AD to 899AD, when the smaller kingdoms started coalescing into larger kingdoms.

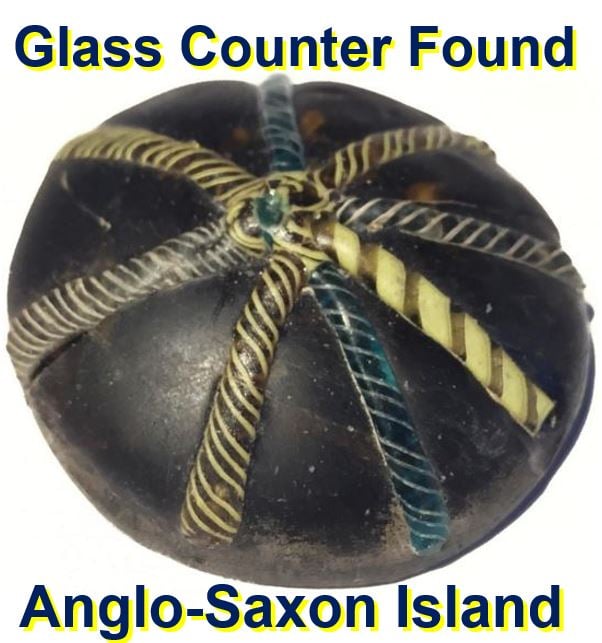

A glass counter adorned with twisted colorful strands was found at the site where the Anglo-Saxon island used to be. (Image: University of Sheffield)

A glass counter adorned with twisted colorful strands was found at the site where the Anglo-Saxon island used to be. (Image: University of Sheffield)

Discovered by a man with a metal detector

The remarkable discovery was made by Graham Vickers, a local metal detectorist, who found an interesting item and reported it to Dr. Adam Deubney, the Lincolnshire Finds Liaison Officer, from the Portable Antiquities Scheme which encourages people in England and Wales to record archaeological objects.

Mr. Vickers found a silver stylus dating back to the 8th century in a disturbed plough field.

A stylus is an ancient writing implement, consisting of a small rod with a point at the end for scratching letters on wax-covered tablets, and a blunt end for erasing (obliterating) them.

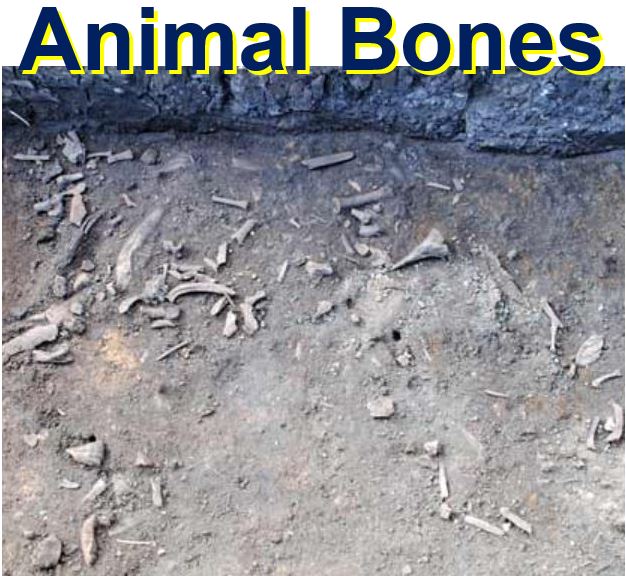

Butchered animal bones discovered by the archaeological team. (Image: culture24.org.uk)

Butchered animal bones discovered by the archaeological team. (Image: culture24.org.uk)

The stylus was the first of several unusual items unearthed at the site, which held some important clues to the significant settlement lying below.

So far, the archaeologists have discovered:

– 21 styli,

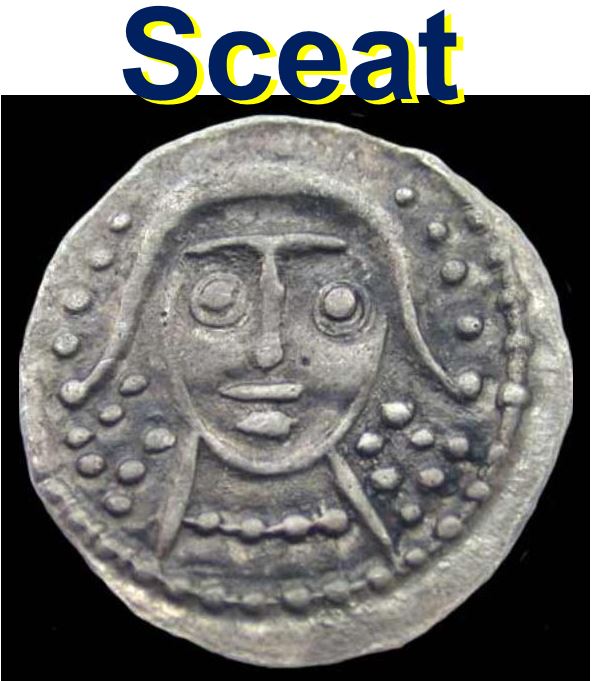

– several Sceattas coins from the 7th and 8th centuries (Sceattas – Singular: Sceat – were small, thick silver coins minted in England, Frisia, and Jutland during the Anglo-Saxon period),

– about 300 dress pins,

– a small lead tablet bearing the name ‘Cudberg’ in faint letters, which is a female Anglo-Saxon name.

Technology used to visualise the landscape

After the interesting artefacts were reported, Dr. Hugh Willmott, a Senior Lecturer in European Historical Archaeology, and Pete Townend, a doctoral student, both from the University of Sheffield’s Department of Archaeology, visited the site and carried out geophysical and megnetometry surveys, as well as 3D modelling to visualise the landscape on a large scale.

The imagery revealed that the island they had found was much more obvious than the land today, rising out of its surroundings. In the past, the whole area was a vast marshland.

To complete the picture, the scientists increased the water level digitally to bring it back up to its early medieval height based on the geophysical survey and topography.

This sceat was one of many found on the Anglo-Saxon island in Lincolnshire. (Image: University of Sheffield)

This sceat was one of many found on the Anglo-Saxon island in Lincolnshire. (Image: University of Sheffield)

Regarding the site, Dr. Willmott said:

“Our findings have demonstrated that this is a site of international importance, but its discovery and initial interpretation has only been possible through engaging with a responsible local metal detectorist who reported their finds to the Portable Antiquities Scheme.”

Sheffield University students have so far opened nine evaluation trenches at the site, which revealed a wealth of information about what life may have been like for the people who used to live there.

Little Carlton is in Lincolnshire in the North-East of England. (Image: google.co.uk/maps)

Little Carlton is in Lincolnshire in the North-East of England. (Image: google.co.uk/maps)

The team found several intriguing items – what appears to have been an industrial working area, as well as a large number of butchered animal bones and Middle Saxon pottery.

Dr. Wilmott added:

“It’s been an honour to be invited to work on such a unique site and demonstrate the importance of working with local people on the ground; one of the greatest strengths of the University of Sheffield is its active promotion of an understanding of our shared pasts for all concerned.”

Video – Little Carlton Timelapse of an Anglo-Saxon Island

Sheffield University’s Archaeology Department used a number of 3D modelling processes to understand the site’s topography. For the site at Little Carlton, the team simulated water levels across several centuries. This allowed them to identify the area as previously being an island, which fitted with the locations of finds from the site.