Animal’s body clocks – how they biologically measure the time – are affected not just by how much light there is, but also by colours, researchers from the University of Manchester reported this week. Their findings could have implications for how jet-lag is currently treated.

Dr. Tim Brown, who works at the University’s Faculty of Life Sciences, and colleagues wanted to determine whether animals’ internal circadian clocks (body clocks) were influenced just by brightness (irradiance), or also by the quality (colour) of light.

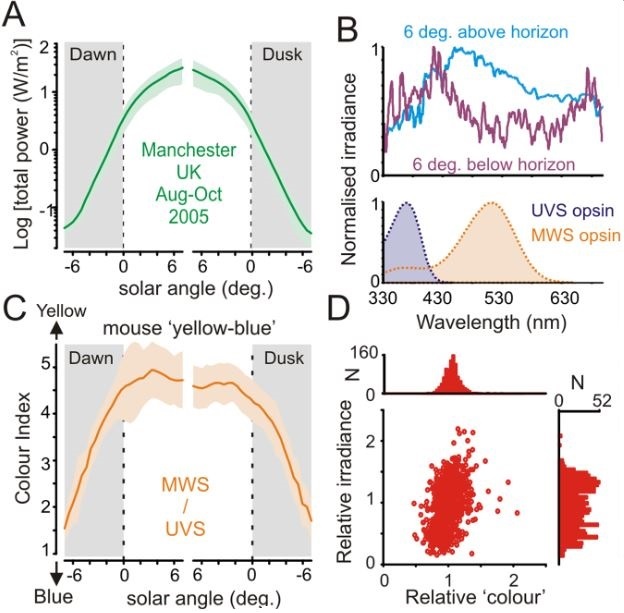

The researchers looked at how light changes around dusk and dawn to determine whether not just light quantity, but also colour could be used by animals to determine what time of day it was.

Spectral composition of ambient illumination is predictive of solar angle. (Image: PLOS Biology)

We know that when the sun sets and rises, light intensity changes considerably. The researchers found that twilight light is considerably bluer than full daytime light.

Animal experiments carried out on mice showed that many of their neurons (nerve cells, brain cells) were more sensitive to changes in colour between yellow and blue than changes in light intensity (brightness).

Dr. Brown and colleagues then stimulated the simulated sky that recreated the daily changes in brightness and colour, as they were measured at the top of the faculty’s Pariser Building for more than four weeks.

As one would expect with nocturnal animals, the mice, which had been placed under the artificial sky for several days, displayed the highest body temperatures just after dusk, when the sky was a darker blue, suggesting that their internal circadian clocks were working optimally.

When they just changed the light intensity of the sky, but not the colour, the animals became more active before dusk, thus showing that their internal body clocks were not properly aligned to the 24-hour day-night cycle.

There is more blue during twilight than in the middle of the day.

The authors concluded in an Abstract in the journal:

“Together, these data reveal a new sensory mechanism for telling time of day that would be available to any mammalian species capable of chromatic vision.”

If mice neurons respond to changes from blue to yellow, it means human neurons probably do too.

Perhaps, rather than advising air passengers who travel through several time zones to wear sunglasses, which just reduce light intensity, a more effective remedy for jet-lag might be some kind of colour therapy.

Citation: “Colour As a Signal for Entraining the Mammalian Circadian Clock,” Lauren Walmsley, Lydia Hanna, Josh Mouland, Franck Martial, Alexander West, Andrew R. Smedley, David A. Bechtold, Ann R. Webb, Robert J. Lucas. PLOS Biology. Published 17 April, 2015. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002127.