A new bacterium – Ideonella sakaiensis – that gobbles up plastic bottles and containers, may be the Holy Grail that scientists and environmentalists have been looking for to tackle our ever-growing plastic mountains that overflow our landfills and infest our oceans.

A team of Japanese scientists wrote in the journal Science that the bacterium breaks down and then eats up PET (polyethylene terephthalate), the polymer that is widely used in the making of synthetic fibres, food containers and bottles.

Ideonella sakaiensis could help break down the non-biodegradable polymer, they explained. A polymer is substance that has a molecular structure built up mainly or completely from a large number of similar units bonded together.

Our oceans are getting filthier every year. Could Ideonella sakaiensis be the Holy Grail we have all been looking for? (Image: mpora.com)

Our oceans are getting filthier every year. Could Ideonella sakaiensis be the Holy Grail we have all been looking for? (Image: mpora.com)

Having the opportunity to degrade PET biologically is wonderful, wrote biochemist Dr. Uwe Bornscheuer in a Commentary in the same journal.

Dr. Bornscheuer, who works at Greifswald University in Germany, added however, that the process is ever so slow, and further studies are needed to determine whether this microbe could eventually be used across the world to effectively break down plastics more rapidly than we are dumping them.

Plastics typically not recycled

Nine percent of the approximately 311 million tonnes of plastics that we produce annually are derived from petrol. Most of these plastics end up being used for packaging, such as making food containers and drinking bottles.

We only recycle about fourteen percent of these plastics, and throw away the remaining eighty-six percent.

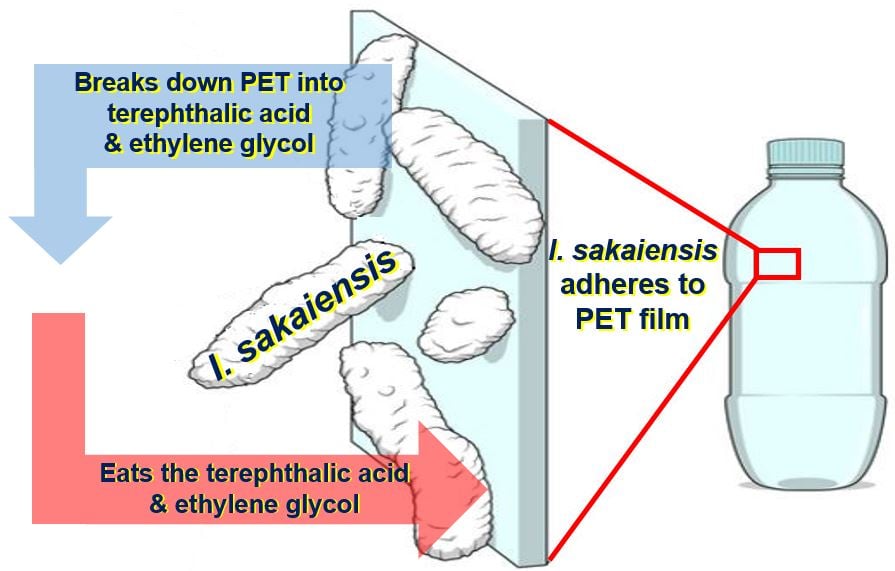

The bacterium sticks to the surface, breaks down the PET into two environmentally benign substances, and eats them up.

The bacterium sticks to the surface, breaks down the PET into two environmentally benign substances, and eats them up.

Nearly all the plastics we make and throw out constitute a significant environmental hazard, because they degrade extremely slowly, especially in our oceans, which according to environmentalists are becoming giant dumping grounds for microplastics.

We could overcome this problem by making degradable plastics from renewable sources. This would be great for the future, but we would still have mountains of plastics everywhere and filthy oceans.

According to previous studies, there are some types of fungi that can break down PET biologically. Shosuke Yoshida, a microbiologist who works at the Kyoto Institute of Technology’s Faculty of Textile Science, wondered whether bacteria might be able to digest PET, and if so, could they be used to combat the plastic waste problem.

Dr Yoshida and colleagues from Keio University’s Department of Biosciences and Informatics, the Life Science Materials Laboratory, and the Ecology-Related Material Group Innovation Research Institute (all in Japan), visited a recycling plant and gathered two-hundred and fifty samples of PET waste debris, in which they discovered that a wide range of different types of microbes had adopted the rubbish as their habitat.

Plastic-eating Ideonella sakaiensis discovered

All the microbes were thoroughly screened to determine whether any of them had PET-destroying or eating properties. They eventually came across I. sakaiensis, a hitherto unknown bacterium, which was identified as a PET eater – they saw that it was decomposing the polymer.

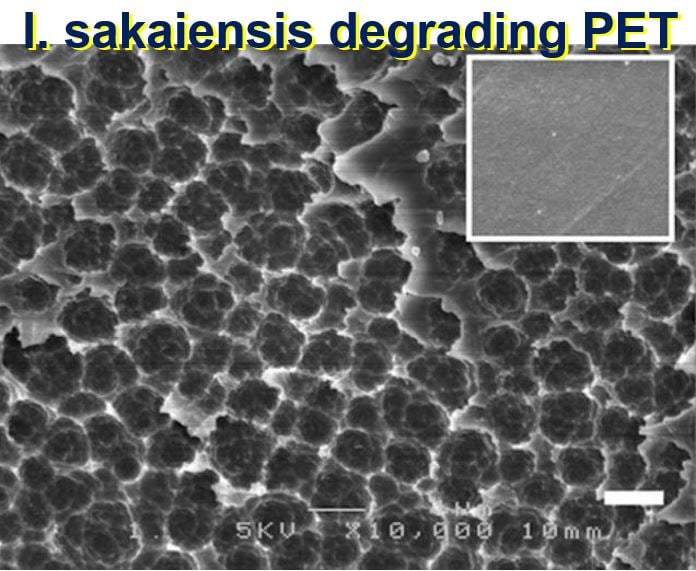

A scanning electron microscope image shows PET film degraded by the 201-F6 bacterium (inset is intact PET film). (Image: aaas.org/news. Credit: Yoshida et al.)

A scanning electron microscope image shows PET film degraded by the 201-F6 bacterium (inset is intact PET film). (Image: aaas.org/news. Credit: Yoshida et al.)

The microbe adhered to a low-grade PET film and used two enzymes to break down the plastic into terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol, which they then gobbled up. The two substances are environmentally benign.

According to the scientists, I. sakaiensis can degrade a low-grade plastic water bottle completely within a period of six weeks.

This is great news! The only problem is that virtually all plastic bottles are made of a higher-grade PET. In order to get the bacterium to effectively break it down within a decent time-frame, it is necessary to ‘cook the plastic’ – it needs to be heated and then cooled before I. sakaiensis can eat it.

According to Dr. Bornscheuer, in theory the bacterium could be added to landfills to speed up the rotting process. “The rate of degradation is rather slow, but it works. This should be improved by further studies on this strain,” he wrote.

While the identification of this PET-eating bacterium is wonderful, much mystery surrounds I. sakaiensis. “We are surprised at the presence of this bacterium that degrades and assimilates PET, whose commercial production was initiated only [a little more than] 60 years ago, meaning that during such a short time the 201-F6 have evolved an efficient system to metabolize PET,” Dr. Yoshida said.

Writing in the news section of the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) website, Michelle Hampson quotes Dr. Yoshida as saying:

“Many things are left uncovered,” explains Yoshida. “For example, although PETase showed higher PET-[degrading] activity, the activity level is actually too low for industrial application.”

“We have to answer the fundamental questions such as why PETase is more active and specific to PET compared to other PET-[degrading] enzymes,” he added, “which could lead to creating the engineered enzyme appropriate for the practical use in the future.”

We have become plastic crazy

Since the 1950s, we have become more and more dependent on plastics, and have reached a point where we would be completely unable to cope without them.

Look at how our annual global plastic production has grown:

– 1950: 50 million tonnes.

– 2008: 245 million tonnes.

– 2016: 311 million tonnes.

In just eight years – 2008 to 2016 – global plastic production jumped by 30%. With large-population emerging economies like those of China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Russia, Mexico and Turkey catching up rapidly with the rich nations, plastic consumption, and thus production, will continue growing at an accelerated rate.

Plastic is incredibly cheap and super versatile, with properties that make it the ideal product for literally hundreds of applications. Add to this the ‘disposable’ lifestyle we have adopted, and we have an environmental time bomb.

We throw away most of the plastic we produce and consume. In fact, most people would be shocked at the incredibly short ‘working life’ of plastic products.

Did you know that the working life of the average plastic bag is only 15 minutes? Each year, we use more than 500 billion plastic bags – that is an incredible 1 million bags each minute of the day!

According to Bira, a water filtration company, over thirty-five billion plastic water bottles are thrown away each year in the United States alone.

Regarding the history of plastic production, plasticoceans.net says:

“Over the last ten years we have produced more plastic than during the whole of the last century. Plastic accounts for around 10% of the total waste we generate.”

Citation

“A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly(ethylene terephthalate),” Ikuo Taniguchi, Shosuke Yoshida, Kiyotsuna Toyohara, Hironao Yamaji, Yasuhito Maeda, Kenji Miyamoto, Kazumi Hiraga, Toshihiko Takehana, Yoshiharu Kimura & Kohei Oda. Science. 11 March 2016. DOI: 10.1126/science.aad6359.

There are many types of pollution. Artificial light, noise, smoke, airborne particulates, and household waste, for example, are possible pollutants.