Why did the ancestors of modern birds survive and thrive, unlike dinosaurs following the mass extinction after a large asteroid impact 66 million years ago? A team of Canadian scientists believe it was because the ancient toothless creatures with beaks that gave rise to modern birds ate seeds, but dinosaurs didn’t.

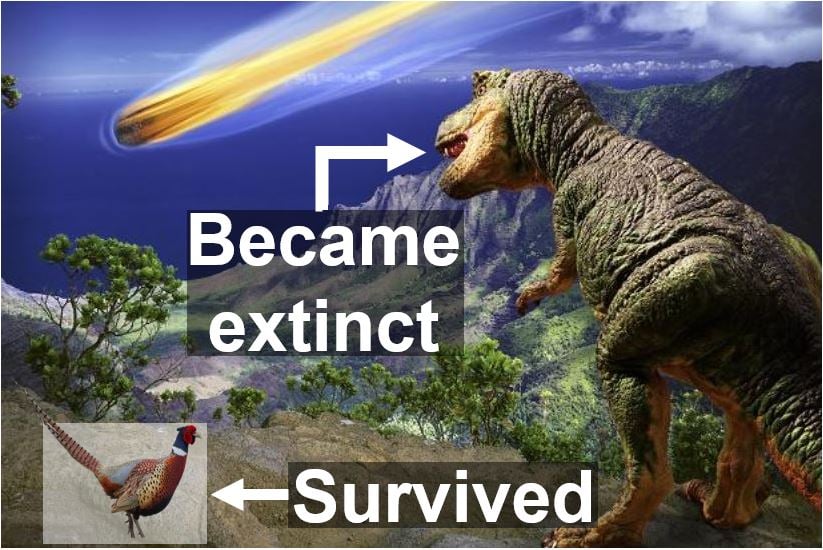

The argument that giant and large animals, such as Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops, died off because of their size, while birds made it through because they were small, cannot explain why smaller bird-like dinosaurs also disappeared alongside their giant cousins.

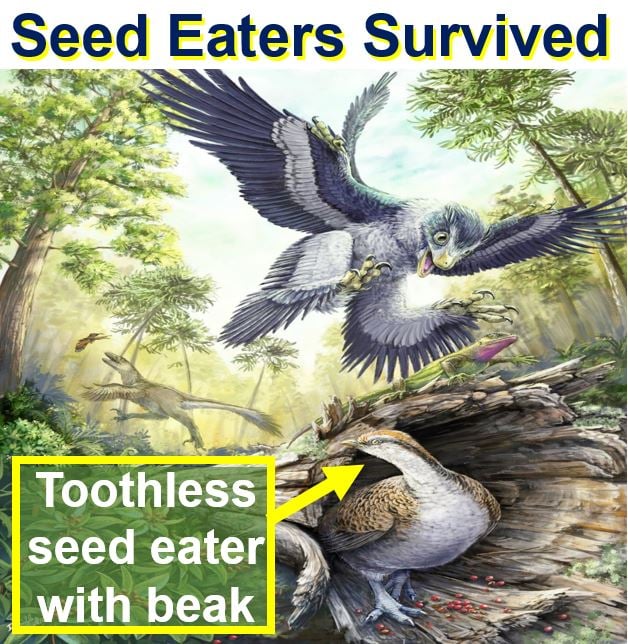

A drawing of some bird-like dinosaurs in their environment in the Hell Creek Formation at the end of the Cretaceous. At the bottom of the image is a hypothetical toothless bird, closely related to the earliest modern birds. Above the toothless bird and in the background are two different dromaeosaurid species hunting vertebrate prey. (Image: eurekalert.org. Credit: Danielle Dufault)

A drawing of some bird-like dinosaurs in their environment in the Hell Creek Formation at the end of the Cretaceous. At the bottom of the image is a hypothetical toothless bird, closely related to the earliest modern birds. Above the toothless bird and in the background are two different dromaeosaurid species hunting vertebrate prey. (Image: eurekalert.org. Credit: Danielle Dufault)

Mystery of survival and deaths during mass extinction solved?

Why some animal species died off while others survived has been a mystery ever since we started studying fossils, that is, possibly until now.

Derek Larson, a paleontologist at the Philip J. Currie Dinosaur Museum in Alberta, Canada, and PhD candidate at the University of Toronto, and colleagues suggested in the journal Current Biology (citation below) that abrupt ecological changes following the asteroid impact may have affected carnivorous bird-like dinosaurs more severely, while early modern birds with toothless beaks managed to survive on seeds when other sources of food were in short supply.

“The small bird-like dinosaurs in the Cretaceous, the maniraptoran dinosaurs, are not a well-understood group.”

“They’re some of the closest relatives to modern birds, and at the end of the Cretaceous, many went extinct, including the toothed birds–but modern crown-group birds managed to survive the extinction. The question is, why did that difference occur when these groups were so similar?”

After the asteroid impact 66 million years ago, all dinosaurs became extinct. Toothless creatures with beaks (modern birds’ ancestors) survived by eating seeds. A previous study suggested that dinosaurs were already in decline when the meteor hit, indicating that the impact sped things up, rather than being the main cause of their extinction.

After the asteroid impact 66 million years ago, all dinosaurs became extinct. Toothless creatures with beaks (modern birds’ ancestors) survived by eating seeds. A previous study suggested that dinosaurs were already in decline when the meteor hit, indicating that the impact sped things up, rather than being the main cause of their extinction.

Was it an abrupt or gradual extinction?

Mr. Larson, together with David Evans from the Royal Ontario Museum & the University of Toronto, and Caleb Brown who works at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, started by trying to find out whether the extinction at the end of the Cretaceous was an abrupt event or a gradual decline – a process which the meteor impact then capped off.

According to the fossil record, evidence supports both scenarios, depending on which dinosaurs you examine.

While investigating the bird-like dinosaurs, Mr. Larson gathered and analyzed data describing 3,104 fossilized teeth from four different maniraptoran families. Some had already been published, but a large part of the data came from Larson’s own work using a microscope, cataloging the size and shape of each tooth.

In this latest study, the scientists were looking for patterns of diversity in their specimens’ teeth, which spanned 18 million years – up until the end of the Cretaceous.

If the variation between teeth decreased over time, the researchers reasoned, this loss of diversity would suggest that the ecosystem was in decline and may have paralleled a long-term loss of species.

David Evans (left), Derek Larson (middle) and Caleb Brown.

David Evans (left), Derek Larson (middle) and Caleb Brown.

If, however, the teeth maintained their differences over time, that would suggest that over millions of years the ecosystem was rich and stable, pointing to an abrupt ending caused by an event at the end of the Cretaceous.

Extinction of many species occurred abruptly

Their findings suggested, according to the tooth data analyzed, that the latter occurred – the species abruptly became extinct.

Mr. Larson said:

“The maniraptoran dinosaurs maintained a very steady level of variation through the last 18 million years of the Cretaceous. They abruptly became extinct just at the boundary.”

The team members suspected that diet may have played a role in promoting the survival of the lineage that produced today’s birds, and they used dietary data and previously-published group relationships from modern-day birds to infer what their ancestors might have been eating.

Working backwards, Larson, Evans and Brown hypothesized that the last common ancestor of modern birds was a toothless creature with a beak that ate seeds.

They survived by eating seeds

Coupled with the tooth data suggesting an abrupt extinction during the Cretaceous, the authors believe that several lineages giving rise to modern birds were those able to survive on seeds after the asteroid struck.

The meteor’s impact would have affected sun-dependent leaf and fruit producing plants. However, hardy seeds could have been a food source until other alternatives became available.

Mr. Larson said:

“There were bird-like dinosaurs with teeth up until the end of the Cretaceous, where they all died off very abruptly. Some groups of beaked birds may have been able to survive the extinction event because they were able to eat seeds.”

The study was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Doris O. and Samuel P. Welles Research Fund, and the Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Citation: “Dental Disparity and Ecological Stability in Bird-like Dinosaurs prior to the End-Cretaceous Mass Extinction,” Derek W. Larson, Caleb M. Brown and David C. Evans. Current Biology, Vol. 26 Iss. 7, April 4, 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.039.