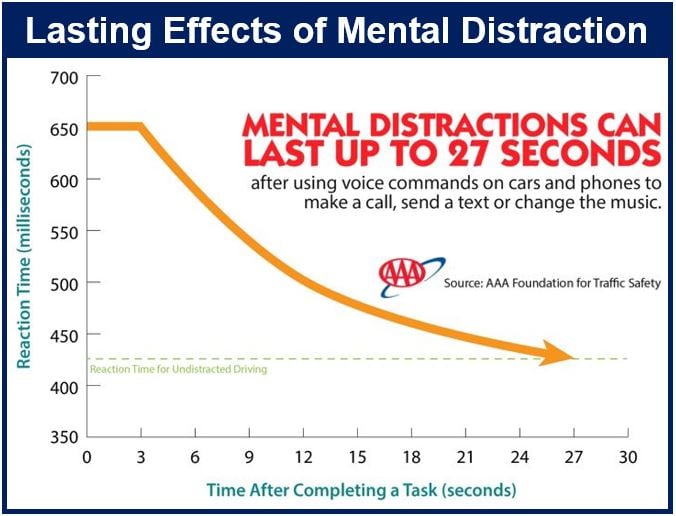

When you talk to your car infotainment system, you may not regain full attention for up to twenty-seven seconds after your last voice-command, American researchers warned after carrying out two separate studies for the AAA Foundation for Science.

The inattention also occurs if you talk to your smartphone while driving – in fact, the effect is the same even if you are stopped at a red light, the researchers said.

One of the studies found that using voice commands to dial phone numbers is highly distracting, as are commands instructing your system to send texts or change music with Google Now, Apple Siri and Microsoft Cortana personal assistant.

This graphic illustrates a key finding of two University of Utah studies on driver distraction using voice-commands. (Image: University of Utah)

This graphic illustrates a key finding of two University of Utah studies on driver distraction using voice-commands. (Image: University of Utah)

Of all the systems tested, Google Now appears to be the least highly distracting.

The other study, which examined music selection and voice-contact dialing using several in-vehicle infotainment systems in 10 model-year 2015 vehicles, rated three of them as ‘moderately distracting’ and six as ‘highly distracting’. The system within the 2015 Mazda 6 was ‘very highly distracting’.

Senior author, David Strayer, a psychology professor at the University of Utah, said:

“Just because these systems are in the car doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to use them while you are driving. They are very distracting, very error prone and very frustrating to use. Far too many people are dying because of distraction on the roadway, and putting another source of distraction at the fingertips of drivers is not a good idea. It’s better not to use them when you are driving.”

Older drivers more susceptible to prolonged inattention

Older drivers, who are most likely to purchase vehicles with an infotainment system, are much more distracted than their younger counterparts when giving voice commands, the researchers found.

Most surprising, according to the authors, was finding that drivers travelling at just 25 mph continued to be distracted for up to 27 seconds after communicating with their car or smartphone voice-command systems.

A motorist volunteer being monitored by a researcher. (Image: University of Utah)

A motorist volunteer being monitored by a researcher. (Image: University of Utah)

Even with the ‘moderately distracting systems’, it took up to 15 seconds before the drivers were back to full alertness.

At 25 mph, a driver covers the length of three football fields over a period of 27 seconds.

Prof. Strayer said:

“Most people think, ‘I hang up and I’m good to go.’ But that’s just not the case. We see it takes a surprisingly long time to come back to full attention. Even sending a short text message can cause almost another 30 seconds of impaired attention.”

Focus on entertaining driver at cost of safety

Co-author Joel Cooper, research assistant professor of psychology at the University of Utah, said:

“The voice-command technology isn’t ready. It’s in the cars and is billed as a safe alternative to manual interactions with your car, but the voice systems simply don’t work well enough.”

“Many of these systems have been put into cars with a voice-recognition system to control entertainment: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, Facetime, etc. We now are trying to entertain the driver rather than keep the driver’s attention on the road.”

According to the US Department of Transportation, 3,154 Americans died and 424,000 others were injured in road accidents involving driver distraction in 2013.

In-vehicle information systems “ought not to be used indiscriminately” while driving, the AAA urges. It also advises caution when talking to your smartphone when driving.

This graphic shows the mental distraction scores for 10 in-vehicle infotainment systems and 3 smartphone personal assistants. (Image: University of Utah)

This graphic shows the mental distraction scores for 10 in-vehicle infotainment systems and 3 smartphone personal assistants. (Image: University of Utah)

How distracting were the in-vehicle systems?

The Utah-AAA studies measure distraction levels as follows: Mild distraction: 1 point; Moderate distraction: 2 points; High distraction: 3 points; Very high distraction: 4 points; Maximum distraction: 5 points.

The two new studies gave the following distraction scores:

– Hand-held mobile phone calls: 2.5,

– Hands-free mobile phone calls: 2.3,

– Listening to an audio book: 1.7,

– Listening to the radio: 1.2.

In-vehicle information systems distraction rating:

– Chevy Equinox with MyLink: 2.4,

– Buick Lacrosse with IntelliLink: 2.4,

– Toyota 4Runner with Entune: 2.9,

– Ford Taurus with Sync MyFord Touch: 3.1,

– Chevy Malibu with MyLink: 3.4,

– Volkswagen Passat with Car-Net: 3.5,

– Nissan Altima with Nissan Connect: 3.7,

– Chrysler 200c with Uconnect: 3.8,

– Hyundai Sonata with Blue Link: 3.8,

– Mazda 6’s Connect system: 4.6.

In some cases, the same system registered different distraction scores in different models. The researchers suggest this may be due to varying amounts of road noise and different microphones being used.

How distracting were the smartphone systems?

The second study looked at the three major smartphone personal assistants. There are two scores below – the first one rated giving voice commands only to change music or make calls while driving, and the second score was for sending texts by voice commands.

– Google Now: 3.0 and 3.3,

– Apple Siri: 3.4 and 3.7,

– Microsoft Cortana: 3.8 and 4.1.

Regarding both smartphone personal assistants and in-car information systems, Prof. Strayer said:

“These systems are often very difficult to use, especially if you’re just trying to entertain yourself. … The vast majority of people we tested ended up being frustrated by the complexity and error-prone nature of the systems.”

When not to use voice-command systems

Prof. Strayer says he never makes hands-free mobile phone calls while driving. He advises motorists not to use voice command systems while driving for purposes such as voice dialing, surfing the Internet, voice contact calling, sending texts or emails, reading emails, updating Facebook, or tweeting.

Prof. Strayer said:

“If you are going to use these systems, use them to support the primary task of driving – like for navigation or to change the radio or temperature – and keep the interaction short.”

Video – Mental distraction while driving

In this video (a separate study to the ones described above), Prof. Strayer administers a demanding cognitive test that was used in a driving simulator to demonstrate the potential distraction effect of using a cell phone while driving.