Are the government shutdowns and debt ceiling fights worth the costs and consequences? Philip Wallach of the Brookings Institution does not think so. The debt ceiling is the maximum amount of money the U.S. Treasury can borrow.

He believes the consequences of the debt ceiling fights far exceed any benefits from the policy; he adds “conservatives, in particular, should demand a change.”

Ever since the squabbles of mid-2011, many Americans and onlookers from farther afield have come to see the debt ceiling as a time-bomb of disaster ticking away, and the debt ceiling fights as an idiosyncrasy of modern American politics.

At best it is seen as a “disorderly defense against government spending” – an out-of-place relic.

However, Wallach points out that several fiscal conservative still defend the debt ceiling as a device to focus minds on debt in America’s otherwise short-sighted and haphazard budgetary process.

For players in the debt ceiling fights, two points to consider

Wallach raises two key arguments that defenders of maintaining the debt ceiling should consider:

A roach motel for opponents – it does not offer fiscal conservatives a powerful weapon. Rather, it offers a type of roach motel for opponents of the debt. “They can go in for the chance to make self-righteous jeremiads, but they can’t escape until they’ve capitulated.”

The costs of debt ceiling brinkmanship – many defenders of the debt ceiling believe the costs are negligible, because Congress will always come to some kind of agreement at the eleventh hour. Wallach asks “How sure are you about that? If we think probabilistically, and admit even a small chance that the maneuver will go wrong, its expected value turns sharply negative.”

Read the whole thing in the National Review Online for an elaboration.

In an article in FixGov, Wallach walks the reader through the likely mechanics of rendering the debt ceiling suitably obscure via expansion of the McConnell Rule or the Gephardt Rule.

The Gephardt rule was thought up by Missouri Congressman, Richard Andrew “Dick” Gephardt. It considerably helped reduce the impact of the debt ceiling until 1995 when it was waived. The rule dictated that each time the House passed its annual budget, the debt ceiling would automatically go up to cover the obligations of that budget.

This is a sensible approach. It represents an acknowledgment by lawmakers that if they agree on set expenditures, knowing that it will result in deficit spending, this requires the issue of more debt. Wallach adds “In our current age of broken budgets, though, we would need to ensure that the rule would cover all continuing resolutions, too.”

The McConnell Rule – Wallach describes this as a kind of formal acknowledgement of the debt ceiling’s rhetorical character. The rule dictates that the US President can raise the debt ceiling by a specific amount, unless Congress passes a joint resolution turning it down. The President would then have the opportunity to veto.

All the anti-debt squabbling would still be there. However, the President would be able to raise the debt ceiling unless two-thirds of both houses of Congress opposed him or her.

In 2011 and 2013 versions of the McConnell Rule were used in a time-limited way. It would not be difficult to adopt it on a permanent basis. Wallach writes “That would pretty well neuter the debt ceiling, and would be an acceptable result.”

He adds that the US Treasury is in favor of adopting this course, and Senator Charles E. Schumer will probably put forward this legislation.

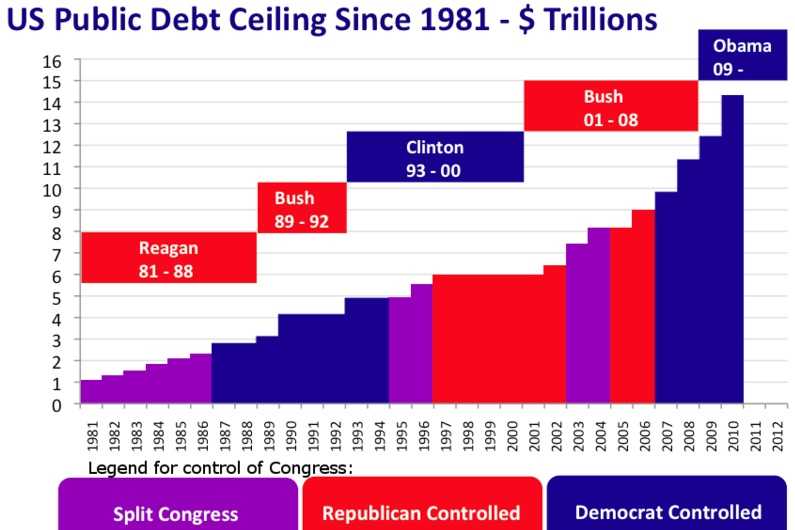

Both Republicans and Democrats raise the debt ceiling

Both Republicans and Democrats can talk until they are blue in the face about fiscal control. Over the last thirty years neither party has been able to stop the borrow and spending cycle.