Dog’s have been our best friends since about 15,000 years ago, and not 30,000, researchers from Skidmore College in New York and the University of Rey Juan Carlos in Madrid suggest, after carrying out a new 3-D fossil analysis.

Professor Abby Grace Drake’s and Michael Coquerelle’s findings, which were published in the journal Scientific Reports (citation below), challenge the long-held belief that dogs started being domesticated during the late Paleolithic era of 30,000 years ago.

Paleontologists (they study fossils) have long debated about when dogs were first domesticated. Was it when humans were still hunter-gatherers during the Paleolithic era, or when their lifestyles were no longer nomadic and they had become farmers during the Neolithic era?

Biologist Prof. Abby Grace Drake at work in her lab. (Image: Skidmore College)

While genetic analyses suggest humans had dogs 30,000 years ago, original fossil finds point to the Neolithic era.

Recent fossils found in Belgium and Russia have been used to show that when our human ancestors were nomadic hunter-gatherers during the late Paleolithic era, they had domesticated dogs.

However, these genetic analyses of the evolutionary history of modern and ancient dogs, as well as the identification of fossil canids (mammals of the dog family) either as dog or wolf can only make sense if there are precise methods of classification based on morphological data, i.e. data on their form and structure. To date, these methods have not existed.

Belgian and Russian fossils were wolves

In this latest study, lead authors Prof. Drake and Mr. Coquerelle used a 3-D method for measuring the canid skulls and re-assessed the Paleolithic fossils from Belgium and Russia.

They compared their forms to that of ancient and modern dogs and wolves from Europe and North America. They were surprised to find that they were not fossils of dogs – they were, in fact, wolves!

“Scientists have been eager to put a collar on the earliest domesticated dog. Unfortunately their analyses weren’t sensitive enough to accurately determine the identity of these fossils. The difference between a German shepherd skull and a wolf skull is subtle – you need to measure it in 3D to reliably tell which is which – and the same is true for these fossils.”

In their new study, they included 3-D interactive figures and scans of the skulls which help clearly distinguish dogs from wolves.

Michael Coquerelle. (Image: Skidmore College)

Mr. Coquerelle said:

“The difference between a wolf and a dog is largely about the angle of the orbits: in dogs the eyes are oriented forward, and a pronounced angle, called the stop, exists between the forehead and the muzzle. We could tell that the Paleolithic fossils do not have this feature and are clearly wolves.”

Why did dog domestication not occur until the Neolithic era?

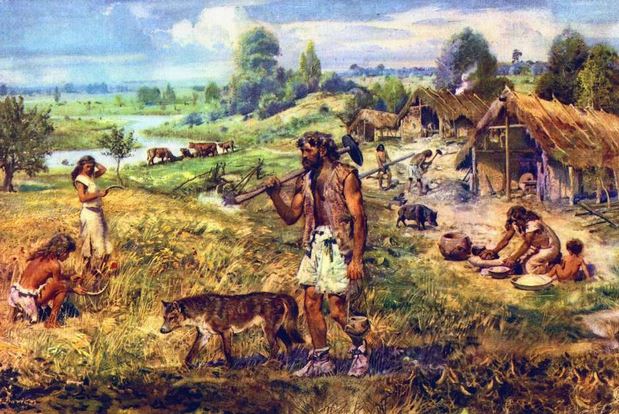

Mr. Coquerelle and Prof. Drake recall Lorna and Ray Coppinger’s hypothesis that wolves started scavenging near settlements when humans had established permanent villages. This was during the Neolithic era.

Permanent settlements created an environment where sustained selection for tameness could exist for several generations “thus setting the stage for dog domestication,” they explained.

Dogs probably did not become domesticated until ancient humans set up permanent settlements.

Although dogs have lived domestically with humans for the past 15,000 years, it was not until about 200 years ago that the first breeds were named, breed standards were introduced, and breed clubs were set up.

Since then, Prof. Drake said:

“We have seen an explosion in dog diversity. People are inherently interested in dogs and we have influenced their evolution,” Drake said, adding, “They are such a part of our lives. Knowing when domestication of dogs took place in the course of human history is important to our story and to theirs.”

Citation: “3D morphometric analysis of fossil canid skulls contradicts the suggested domestication of dogs during the late Paleolithic,” Abby Grace Drake, Michael Coquerelle & Guillaume Colombeau. Scientific Reports 5, Article number: 8299, doi:10.1038/srep08299.