Earth’s hidden groundwater has been mapped for the first time by a team of hydrologists from Canada, the US and Germany. Their findings revealed that less than 6% of groundwater in the top two kilometres of Earth’s landmass is renewable within an average human’s lifetime.

Groundwater is one of Earth’s most precious and most exploited natural resources. It ranges in age from just a few months to several million years.

Among hydrologists, farmers and others across the globe, there is growing demand to know how much groundwater we have and how long it will be before we have tapped it all out.

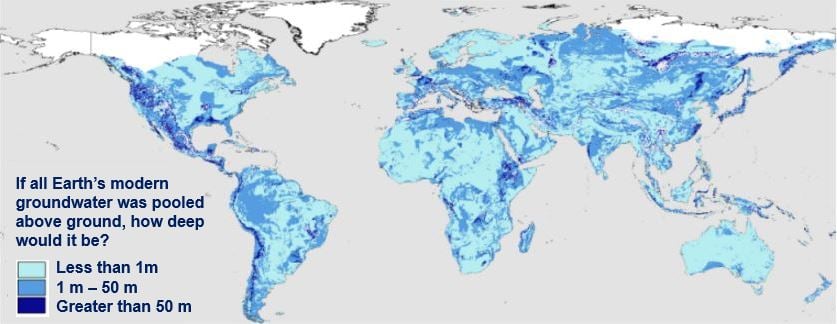

As the groundwater map shows, there is more groundwater below Earth’s mountainous and tropical regions. (Image: University of Victoria)

As the groundwater map shows, there is more groundwater below Earth’s mountainous and tropical regions. (Image: University of Victoria)

For the first time since a limited calculation of the global volume of groundwater was attempted in the 1970s, scientists have produced a comprehensive, data-driven estimate of how much groundwater there is.

Study leader, Dr. Tom Gleeson of the University of Victoria, Canada, along with colleagues from McGill University, and University of Calgary, both in Canada; the University of Texas in the USA; and Georg-August-Universität Göttingen in Germany, published their findings in the academic journal Nature.

Humans consuming groundwater too fast

Regarding the ‘modern’ groundwater (within the top 2 km of Earth’s landmass), 6% of which is renewable within a human lifetime, Dr. Gleeson said:

“This has never been known before. We already know that water levels in lots of aquifers are dropping. We’re using our groundwater resources too fast–faster than they’re being renewed.”

With the ever-growing demand for water globally – especially in light of global warming – this study provides vital data for water managers and policy developers, as well as researchers in the fields of hydrology, geochemistry, oceanography, and hydrology to better manage our groundwater resources in a sustainable way, the authors say.

After gathering and analyzing data from several sources, including nearly one million watersheds and over 40,000 groundwater models, the researchers estimate there is a total volume of nearly 23 million cubic kilometres of groundwater.

Of the total, just 0.35 million cubic kilometres is less than 50 years old.

How long can humans continue pumping up groundwater before it is all gone?

How long can humans continue pumping up groundwater before it is all gone?

Why does old vs. modern groundwater matter?

Why is it so important to differentiate between modern and old groundwater. They are fundamentally different in how they interact with climate cycles and the rest of the water.

Old groundwater, which exists deeper underground, is commonly used as a water resource for industry and farming. It may sometimes contain uranium or arsenic, and is generally more salty than seawater.

In some areas, this old, briny water is so ancient, isolated and stagnant that it should be considered a non-renewable resource, the authors explain.

While the volume of modern groundwater dwarfs all the other components within the active water cycle, and is a much more renewable resource, it is closer to the surface and faster-moving. This means modern groundwater is much more vulnerable to climate change and contamination from human activity.

Most groundwater below mountains and tropical regions

According to the study’s maps, most modern groundwater is in mountainous and tropical regions. Some of the largest deposits are in North and Central America running along the mountain ranges of the Rockies and Andes, the Amazon Basin, Indonesia, and the Congo.

Unsurprisingly, the smallest amount of modern groundwater exists in regions with the least rainfall, such as the Sahara Desert.

As the satellite data did not accurately cover the high northern latitudes, the maps do not include information on that part of the world.

Dr. Kevin Befus, who carried out the groundwater simulations as part of his doctoral research at the University of Texas, and is today a post-doctoral fellow at the United States Geological Survey, said:

“Intuitively, we expect drier areas to have less young groundwater and more humid areas to have more, but before this study, all we had was intuition. Now, we have a quantitative estimate that we compared to geochemical observations.”

So, how long do we have? New study will tell

In order to determine how rapidly we are depleting both modern and old groundwater, an analysis needs to be carried out on volumes of groundwater in relation to how much we are using and depleting, the researchers say.

In a prior study that ultimately lead to the research on modern groundwater, Dr. Gleeson’s 2012 groundwater footprint report (published in Nature) mapped global hotspots of groundwater stress, charting precipitation rates versus rates of use through pumping, mainly for agriculture.

Some of these hotspots are in parts of the US, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Iran, northern China, Pakistan, and northern India.

Dr. Gleeson said:

“Since we now know how much groundwater is being depleted and how much there is, we will be able to estimate how long until we run out.”

To do this, Dr. Gleeson will head a further study using a global scale model.

This study was funded by the US National Science Foundation, the American Geophysical Union, the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, and the Natural Sciences and Research Council.

Citation: “The global volume and distribution of modern groundwater,” Tom Gleeson, Kevin M. Befus, Scott Jasechko, Elco Luijendijk & M. Bayani Cardenas. Nature. 16 November, 2015. DOI: 10.1038/ngeo2590.