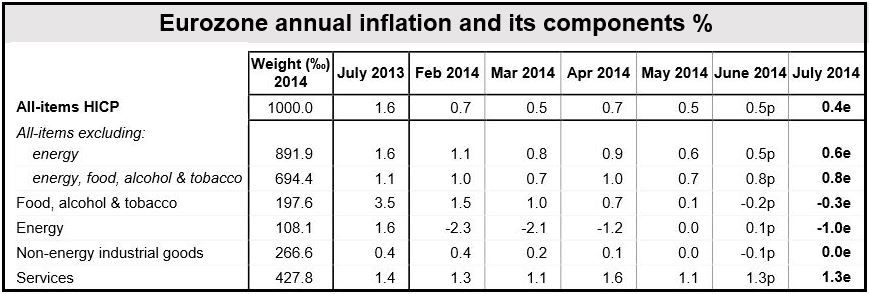

With the Eurozone July inflation rate falling to 0.4% (annualized) from 0.5% in June, economists are seriously concerned that the currency bloc may be sliding into a deflationary spiral. In a deflationary environment people postpone spending, borrow less, and the economy tends to slow right down or even shrink.

Those concerns have been heightened by signs that expanded sanctions against Russia could damage the fragile Eurozone economies.

Core inflation, however, which excludes energy, food, alcohol and tobacco (items with volatile prices), held steady at 0.8%.

Below are data reported by Eurostat on the Eurozone’s main inflation/deflation components for July 2014 (annualized):

- services: +1.3% (the same as in June),

- non-energy industrial goods: 0.0% (-0.1% in June),

- food, alcohol & tobacco: -0.3% (-0.2% in June),

- energy: -1.0% (+0.1 in June).

The European Central Bank (ECB), which has a target of 2% inflation per year, has said that anything below 1% poses a risk of deflation, and that the risk grows the further down inflation slides.

The UK, which chose not to join the Eurozone, posted annual inflation of 1.9% in June, close to the Bank of England’s 2% target.

The danger zone

Mario Draghi, governor of the ECB, had warned that persistent inflation below 1% would be deemed to be in a “danger zone”.

For the last ten successive months inflation has been below 1% (annualized).

(Source: Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union)

What is the Eurozone?

The Eurozone (or Euro Area) is made up of European Union nations that use the euro as their currency, and include Finland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Portugal, Austria, the Netherlands, Malta, Luxembourg, Latvia, Cyprus, Italy, France, Spain, Greece, Ireland, Estonia, Germany and Belgium.

The following countries are in the European Union by have retained their own currency: UK, Sweden, Denmark, Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Hungary, Croatia and Bulgaria.

When referring to all 28 EU members, Europeans often use the term “EU28”.

Why is deflation undesirable?

People who were around in the 1970s, the decade of global high inflation, may wonder what all the fuss is about. Surely, falling prices are great … much better than runaway inflation?

When prices don’t rise, or even start falling, consumers and businesses postpone their purchases, because they believe they will get better deals if they wait. If people spend less, shops and other businesses sell less.

If businesses sell less, they will reduce their prices to boost sales … but consumers, seeing even lower prices postpone their purchases … and the spiral goes on and on. Businesses may have to lay people off if they are selling less – overall the economy may start to shrink and unemployment will rise.

If prices go down wages don’t rise, and may even start falling. People’s debt burden may increase. If your monthly mortgage repayment is $500 and your wages are $2,000 per month, your mortgage payments represent 25% of your income. If your wages fall, those payments will represent a higher percentage of your income, i.e. your debt burden increases.

Japan slid into a deflationary spiral twenty years ago, and has not yet managed to climb out of it.

Unemployment down slightly

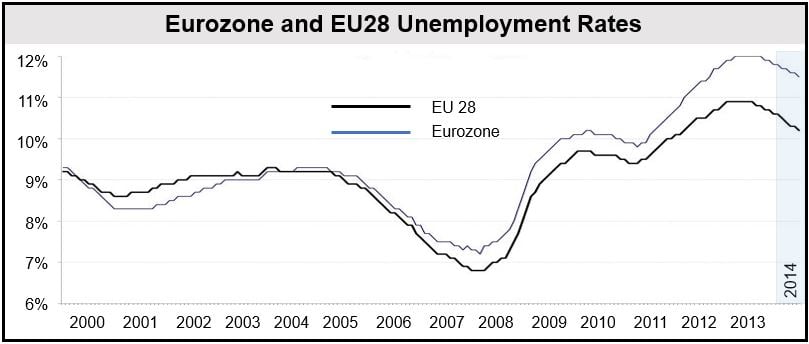

In a separate report, also published by Eurostat, Eurozone unemployment declined marginally from 11.6% in May to 11.5% in June, and 12% in June 2013. June 2014 posted the lowest unemployment rate in the Eurozone since September 2012.

The EU28 unemployment rate in June was 10.2%, compared to 10.3% in May and 10.9% in June 2013.

There are about 25.005 million unemployed people in the EU28 – 18.412 million of them in the Eurozone. There were 198,000 fewer unemployed EU28 citizens in June compared to May, and 1.537 fewer than in June 2013.

In France, Austria and Finland unemployment went up in June.

For the last 10 years, the EU28 unemployment rate has been lower than the Eurozone rate. Does that mean that joining the Euro destroys jobs? (Data source: Eurostat)

Weaker euro may head off deflation

One item of encouraging news is the euro, which reached a high of nearly $1.40 in May and is now trading below $1.34.

With US GDP growth during the second quarter showing surprisingly strong growth, and a Federal Reserve that is starting to sound slightly more hawkish, the euro is likely to fall further against the dollar.

A sliding euro will push up import prices, which in turn will help raise inflation.