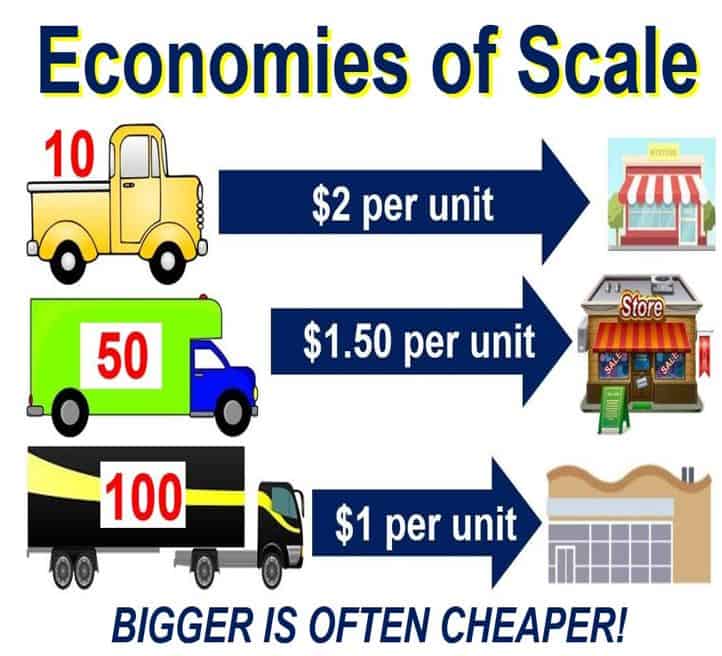

Economies of scale in microeconomics refers to the cost advantages that companies obtain when they increase production – their costs per unit decreases the more they produce.

Diseconomies of scale – the opposite of economies of scale – can also occur when a company expands.

If you produce more, your fixed costs are spread out over more units of output. If you are buying in larger quantities from suppliers you are probably able to get better unit prices.

Economists say that with increased production and sales, greater operational efficiency is generally achieved too, which leads to cheaper variable costs as well.

When sales grow so does production, and the cost per unit goes down. Economies of scale relate to the costs per unit as output increases.

Economies of scale do not only apply to single companies, they also apply to whole nations. For example, economists argue that the UK as part of the European Union (EU), with a market of nearly half-a-billion people, can enjoy much greater economies of scale compared to being on its own in a market of just 65 million inhabitants.

Surprisingly, Britons chose to leave the EU on 23rd June, 2016. Some voters who saw the pound and stock markets slide the next morning, and a general global panic, plus their Prime Minister David Cameron resigning, wondered whether they had made the right decision.

According to economic theory, GDP (gross domestic product) growth may be achieved when economies of scale are realized.

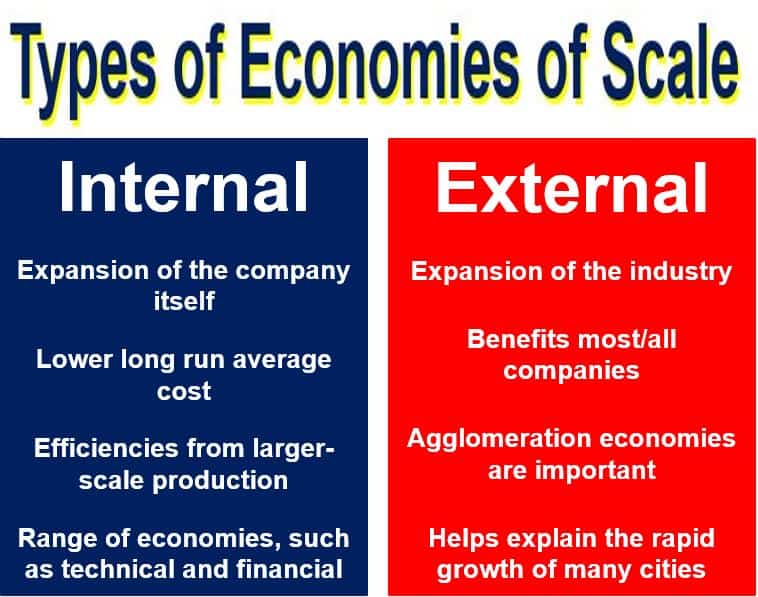

Internal and external economies of scale

There is a difference between external and internal economies of scale. When a firm reduces costs and raises production, internal economies of scale have been realized.

External economies of scale, as the term suggests, occur outside of a company, within an industry. External economies of scale are not linked to ability, skill, education, management or experience. The industry itself may expand.

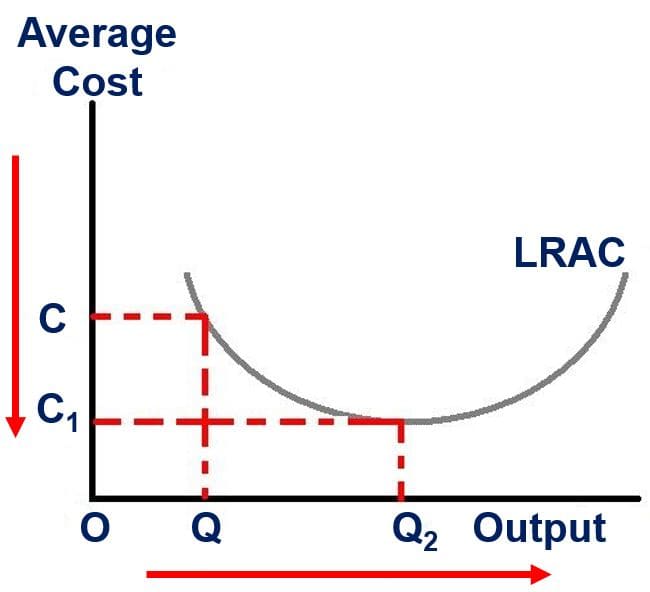

As quantity of production increases from the first quarter to the second quarter (Q to Q2), the average cost of each unit decreases from C to C1. LRAC stands for Long Run Average Cost). (Image: Adapted from Wikipedia)

When an industry expands, the companies within it benefit from better infrastructure, access to skilled labor and more sophisticated supply networks.

Catch 22 situation

Small companies commonly find themselves in a situation in which increasing economies of scale seems virtually impossible.

They want to raise production, but in order to do so need some large orders from existing or new customers. Without increasing production you cannot get greater economies of scale. However, you cannot raise production if you do not have the orders (you can, but it is very risky).

Clients may not be willing to make very large orders if the supplier cannot currently show that it has the production capacity to meet them.

This is known as a Catch 22 situation – an impasse. There are some possible solutions: 1. Find an investor so that you can purchase the necessary equipment to meet larger orders. 2. Apply for a bank loan. 3. Sell more shares. 4. Merge with another company.

Internal economies of scale are a consequence of the growth of the business itself. External economies of scale occur outside the company, within an industry.

Small markets

In a very small market, such as Liechtenstein, which has a population of just 37,000, companies need to export for decent economies of scales to be achieved. Free trade policies are much more important for countries with smaller populations – smaller markets.

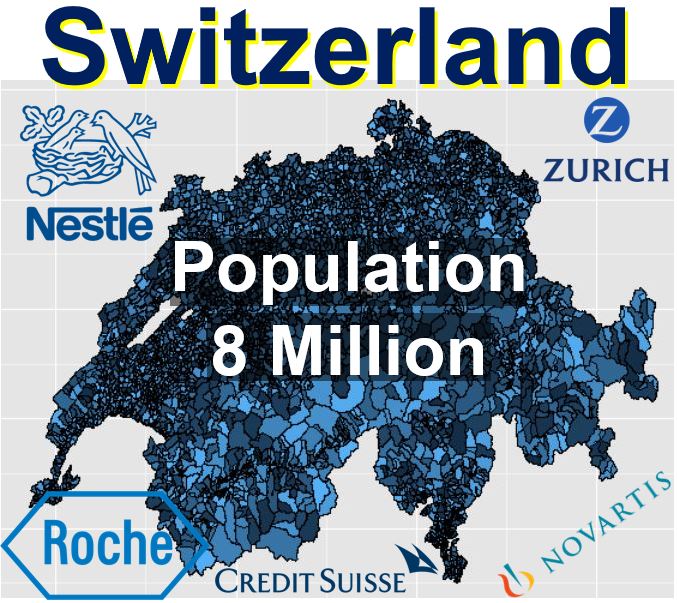

If you look at small markets among advanced economies, like Switzerland, the Netherlands and Sweden, you will see that they have a very high percentage of multinational companies with branches in many other countries – companies such as Nestle, Heineken, Volvo, Ericsson, Unilever, Novartis, ING Group, Royal Dutch Shell, and Roche.

If your business is in the United States, you are more likely to reach maximum-possible economies of scale without needing to sell your product or service overseas.

Switzerland has some huge multinational companies. For them to have achieved their current economies of scale they had to expand into other countries, because the Swiss market, with just 8 million inhabitants, is too small. Fortunately, it has three large advanced economies next door – Germany, France and Italy – plus the rest of Europe nearby.

Reasons for economies of scale

Economies of scale occur for a number of different reasons:

– Division of labor: workers can do more specific tasks in larger scale operations. With the minimum of training they can become extremely proficient in their task, which enables significantly greater efficiency. A good example is an assembly line with several different jobs.

– Technical: in some cases, such as building a large factory, high fixed costs are required. If, for example, a car plant was then only used for small-scale production it would not be efficient to run. By using the plant to full capacity, average costs will be considerably lower.

– Buying in bulk: purchases made in large quantities generally have attractive discounts, which bring down unit costs. That is why major supermarket chains get much lower prices from their suppliers than small individual shops do. If you sell strawberries to a supermarket, which buys 5 tons every month, and also to a small shop, which buys 100 kg every month, the supermarket will probably be paying much less per kilogram than the shop.

– Spreading overheads: if a company merges with another one, it can then rationalize its operational centers. Instead of two head offices, there might just be one now.

– Marketing economies of scale: larger companies can spend on national TV campaigns – something smaller businesses are not able to do.

– Financial economies: a bigger company can obtain better interest rates than smaller businesses.

– Managerial or administrative economies: these arise because the same people can generally manage with greater output, so average administrative costs go down when production rises. Larger companies can take on specialists, which leads to greater efficiency.

– Social economies: these may be developed into those which build up the goodwill of the community and thus attract customers (sponsorship), and those that develop loyalty of the company’s employees (Christmas bonuses).

Diseconomies of scale

Diseconomies of scale are those forces that cause bigger companies and governments to produce goods and services at higher per-unit costs. It is the opposite of economies of scale.

As a company expands its activities beyond the optimum size, unit costs may start rising again. This may occur when an equal percentage rise in inputs leads to a less than equal change in output. Economist call this the diminishing returns, or diseconomies of scale.

Diseconomies of scale can occur externally and internally. Examples of external diseconomies include overcrowding, congestion of roads, increased land prices, and higher labor costs.

Internal diseconomies of scale can occur if humans and machines become overcrowded and get in each other’s way, or lack of coordination leads to greater wastage.

Jamie Dimon, Chairman, President and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, the largest of the Big Four American banks, once said:

“Economies of scale are a good thing. If we didn’t have them, we’d still be living in tents and eating buffalo.”