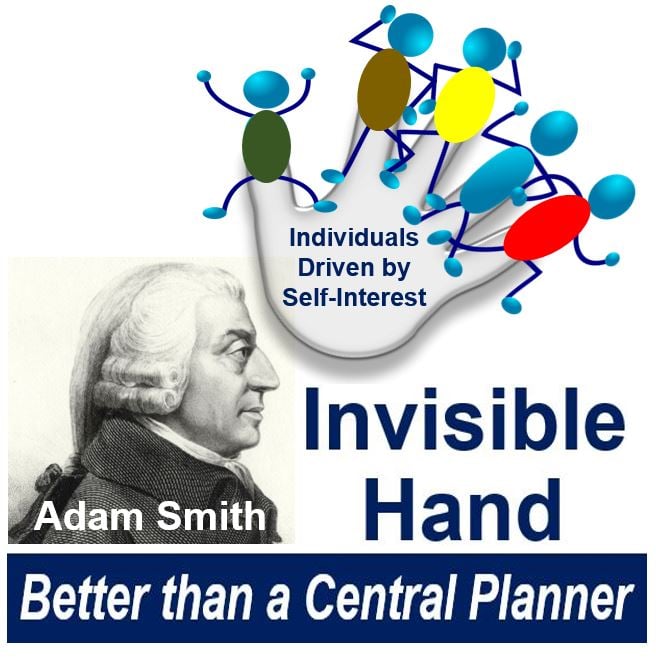

The Invisible Hand is a term that Scottish moral philosopher and political economist Adam Smith (1723-1790) used to describe the unintended social benefits of individual actions.

The term refers to the free market’s ability to allocate factors of production, products and services to their most valuable use. If we all act from self-interest, motivated by profit, then the economy will function more efficiently and productively, than it would if economic activity were directed by some kind of central planner.

In other words, Mr. Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ described how individuals making selfish decisions could collectively and unwittingly contribute to an effective economic system that was in the public interest.

This mechanism underscores the complexity of economic ecosystems, where individual pursuits of wealth creation can inadvertently lead to the efficient allocation of resources across a society.

Mr. Smith, who is known today as the ‘father of modern economics’, used ‘the invisible hand’ with respect to income distribution in 1759 and production in 1776 in his papers The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, respectively.

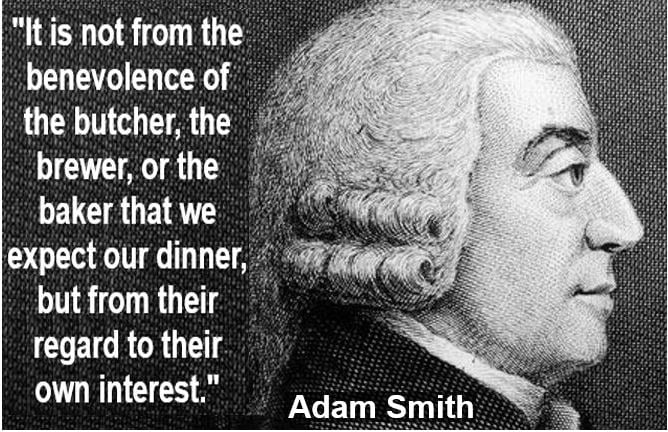

Mr. Smith only used the term three times in his writings. However, the ‘invisible hand’ has come to capture his fundamental belief that society benefits more by individual people’s self-interested actions than actions that are intended to directly benefit society.

Mr. Smith explained that it was as if an invisible hand guided the actions of individual people to combine for the common good. He also recognized that this invisible hand was not flawless, and that sometimes government action was required. Examples he included of government action were laws to protect consumers from monopolistic behaviors, i.e. antitrust legislation, the enforcement of property rights, and to provide national defense and policing.

Smith did not believe there was a real invisible hand. He used the term as a metaphor for how, in a market that is allowed to function freely, basically selfish people operate through a system of mutual interdependence, which overall benefits society.

Smith’s interpretation of the invisible hand

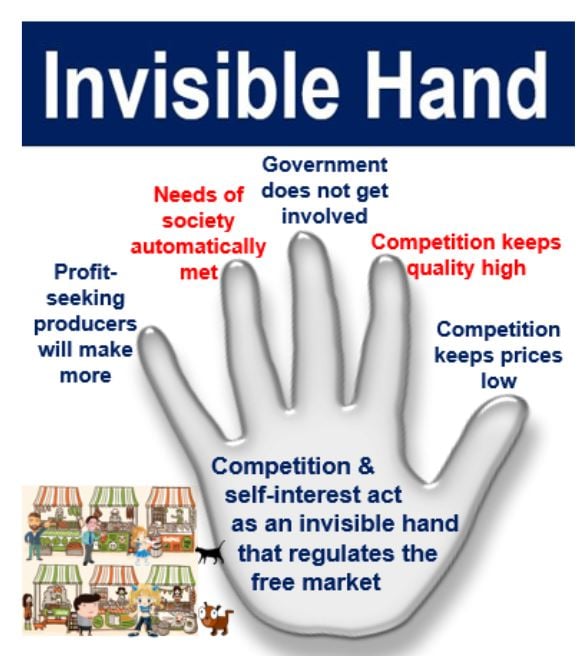

In Mr. Smith’s interpretation, if each consumer is allowed to choose freely what to purchase, and each supplier or producer is allowed to choose freely what to sell and how to make it, the market will settle on the best possible balance of product distribution and prices, which benefits society as a whole.

Self-interest drives the players to beneficial behavior in a case of serendipity (fortunate coincidence). Producers’ desire to maximize profits leads to efficient methods of production.

Producers’ desire to gain market share are achieved by offering the lowest prices possible. Investors invest in those businesses that provide the best returns, and remove their capital from those that are less efficient in creating value.

All these effects – efficient production, low prices, growth of successful businesses that make lots of things we want – occur dynamically and automatically.

Mr. Smith used the metaphor in context of an argument criticizing government regulation of markets and protectionism. Protectionism is a policy some governments adopt to reduce imports by imposing tariffs, quotas and other barriers.

In general, the ‘invisible hand’ can apply to any individual action that has unintended and/or unplanned consequences, particularly those that arise from actions not organized or orchestrated by a central command, and that have an evident, patterned effect on society.

How economists interpreted the invisible hand

Economists have nearly always generalized the concept of the invisible hand beyond Mr. Smith’s original uses.

The phrase was unpopular among economists before the 20th century. In his textbook Principles of Economics, influential British economist Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) never used the term. William Stanley Jevons (1835-1882), a British economist and logician, did not use it in his Theory of Political Economy either.

American economist Paul Samuelson (1915-2009), the first US citizen to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, cited it in his textbook in 1948:

“Even Adam Smith, the canny Scot whose monumental book – ‘The Wealth of Nations’ (1776) – represents the beginning of modern economics or political economy – even he was so thrilled by the recognition of an order in the economic system that he proclaimed the mystical principle of the “invisible hand”: that each individual in pursuing his own selfish good was led, as if by an invisible hand, to achieve the best good of all, so that any interference with free competition by government was almost certain to be injurious.”

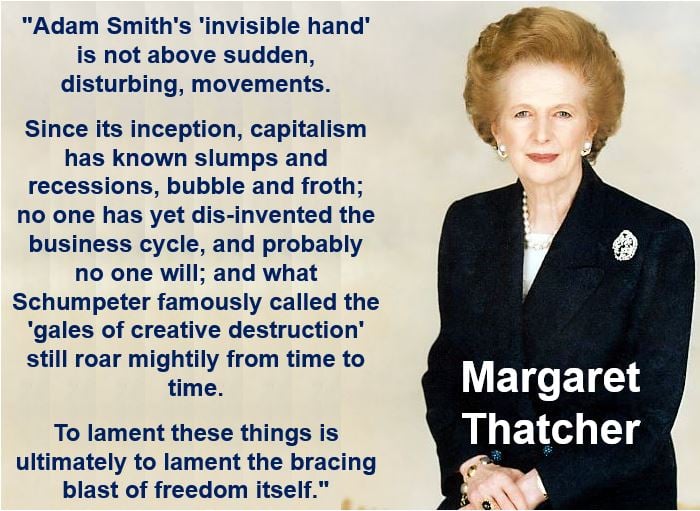

Mr. Samuelson went on to say that Mr. Smith’s ‘unguarded’ conclusion regarding the invisible hand had done almost as much harm as good during the past 150 years.

Many economists today say that the current use of the invisible hand in economic thinking as a symbol of free market capitalism stretches the use and meaning of the term far beyond Mr. Smith’s intentions.

Gavin Kennedy, Professor Emeritus at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, is one of several economists to criticize modern interpretations of the term in this way.

This debate highlights the evolving nature of economic theories as they adapt to the complexities of modern global markets.

Video – What is the Invisible Hand?

This video, from our sister channel on YouTube – Marketing Business Network, explains what the ‘Invisible Hand’ is using simple and easy-to-understand language and examples.