Shareholder value, also known as shareholder value maximization or the shareholder value model, is a term used in the world of business that implies that the definitive measure of a commercial enterprise’s success is on how much it enriches its **stockholders (shareholders). Shareholder value is all about putting shareholders first; a business’ number one priority should be to maximize the total value of its shares.

** Shareholder means the same as stockholder – the word shares means the same as stocks.

Critics of this notion wonder whether focusing too much on shareholder value might be bad for customers, suppliers, the workforce, and other stakeholders.

If a company’s management is able to grow earnings, sales and free cash flow over time, its shares will most probably appreciate in value, which pleases stockholders. Senior management’s strategic decisions, as well as their ability to make the right investments and generate a strong return on invested capital, are the main factors that determine a business’ current and future success.

If the senior managers are able to create this value over the long term, the price of its shares rise, and it can pay hefty cash dividends to its shareholders. It has succeeded in its number one mission – shareholder value.

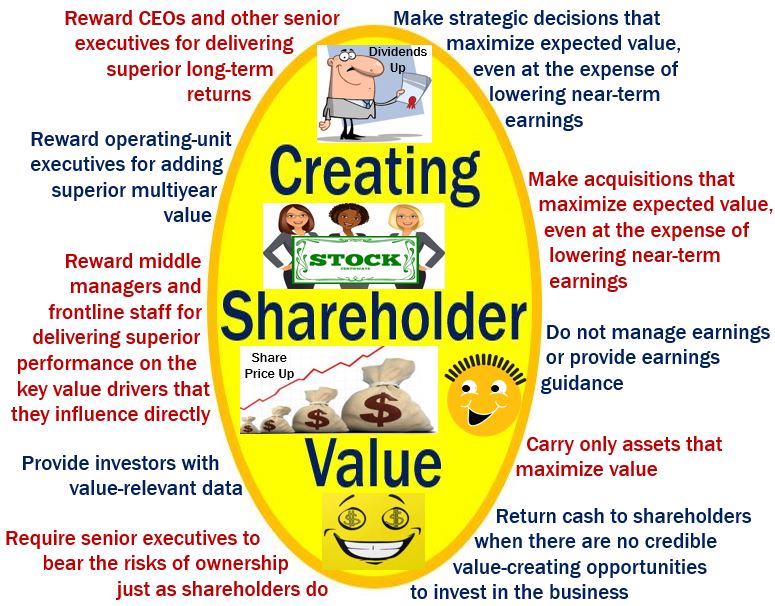

The ten principles listed in this image come from an article written by Alfred Rappaport – ‘Ten Ways to Create Shareholder Value’ – published in the Harvard Business Review in September, 2006.

Shareholder value – a misused term?

We see the term used everywhere, especially by fund managers, shareholder activists and company managers. They all say they are committed to realizing or generating shareholder value. Unfortunately, not many of them then go on to explain what exactly they mean.

Put simply, shareholder value is all about creating additional wealth for the ultimate owners of a company, and whether senior management is acting in a way that achieves this.

In a 2015 article from the Financial Times, writer Terry Smith questioned whether people really understood what “shareholder value” means. He believed the term was often misused or misunderstood.

He explained it like this: a company creates value when it earns more money from its investments than what it costs to get that money (like loans or investor funds). For example, if you borrow money at 10% interest but only make a 5% return, you’re actually losing money. But if you make 20%, you’re making a profit and becoming wealthier.

The same goes for companies—when they consistently earn more than they spend to operate, they grow in value. And if they can keep doing that, it makes sense for them to reinvest some of their profits instead of just handing all of it back to shareholders through dividends or buying back shares. That way, they can keep growing and delivering even more value over time.

Shareholder value or creating customers?

Is the ultimate objective of a business shareholder value or to create a customer?

Surely, in the real market, factories are built, products are researched, designed, developed and produced, real goods and services are purchased and sold, income is earned, costs are met, and real income in the form of profit shows up on the bottom line.

Isn’t that the world that business leaders should try to control?

Shares are traded in the stock market. This is the world where the expectations market exists and shares in businesses are bought and sold among investors.

In this expectations market, investors assess the real market of a commercial enterprise today and, based on that assessment, create expectations as to how the business will likely thrive in the future.

How investors and potential investors view a company’s future likely outcome shapes its stock price in the expectations market. How they expect a company to perform in future shapes its share price.

In an article published in Forbes magazine in November 2011 – ‘The Dumbest Idea In The World: Maximizing Shareholder Value’ – Steve Denning quoted Roger Martin, Dean of the Rotman School of Management (from 1998 to 2013), part of the University of Toronto in Canada, who said:

“What would lead [a CEO] to do the hard, long-term work of substantially improving real-market performance when she can choose to work on simply raising expectations instead? Even if she has a performance bonus tied to real-market metrics, the size of that bonus now typically pales in comparison with the size of her stock-based incentives.”

“Expectations are where the money is. And of course, improving real-market performance is the hardest and slowest way to increase expectations from the existing level.”

In today’s business environment, a CEO is forced to pay careful attention to the expectations market, because if the share price declines steeply, the application of accounting rules classify it as a goodwill impairment (regulation FASB 142).

Cyrus Pallonji Mistry is an Irish-Indian businessman who was Chairman of Tata Group – an Indian multinational giant – from 2012 to 2016. (Image: Adapted from Twitter)

We live in a world where the best managers are the ones who meet expectations.

Martin added:

“During the heart of the Jack Welch era, GE (General Electric) met or beat analysts’ forecasts in 46 of 48 quarters between December 31, 1989, and September 30, 2001 — a 96% hit rate. Even more impressively, in 41 of those 46 quarters, GE hit the analyst forecast to the exact penny — 89% perfection.”

“And in the remaining seven imperfect quarters, the tolerance was startlingly narrow: four times GE beat the projection by 2 cents, once it beat it by 1 cent, once it missed by 1 cent, and once by 2 cents. Looking at these twelve years of unnatural precision, Jensen asks rhetorically: “What is the chance that could happen if earnings were not being ‘managed’?'”

The chances are virtually zero, Martin replied.

Jack Welch was Chairman and CEO of Generic electric from 1981 to 2001 – during that period, the company’s value increased by four thousand percent. He also said: “Shareholder value is a result, not a strategy . . . Your main constituencies are your employees, your customers and your products.” (Image: Wikipedia)

Martin is not alone in believing that our theories of shareholder value maximization and stock-based compensation have the potential to destroy America’s economy and rot the core out of its style of capitalism.

Martin claims that shareholder value has been reduced by a pervasive emphasis on the expectations market. It has created inappropriate and ill-advised incentives, and brought parasitic, bloodsucking players into our markets.

“The moral authority of business diminishes with each passing year, as customers, employees, and average citizens grow increasingly appalled by the behavior of business and the seeming greed of its leaders,” Martin wrote.

Video – creating shareholder value

This Accenture Academy video explains that according to a study carried out from 1993 to 2010, only 41% of the companies in the S&P 500 created value for their stockholders, while the rest – 59% – destroyed it.