Structural unemployment is unemployment that results from industrial reorganization, usually due to a change or advancement in technology, and not fluctuations in supply or demand. Structural unemployment is the most difficult sort to bring down, because rather than being caused by changes in the economic cycle, it is the result of a change in the structure of the economy itself.

When there is cyclical unemployment, there are measures the government can take, such as injecting money into the economy or lowering interest rates to stimulate faster GDP (gross domestic product) growth.

When there is structural unemployment, the only way to reduce it is to change the economic structures that are causing it – that is much more difficult.

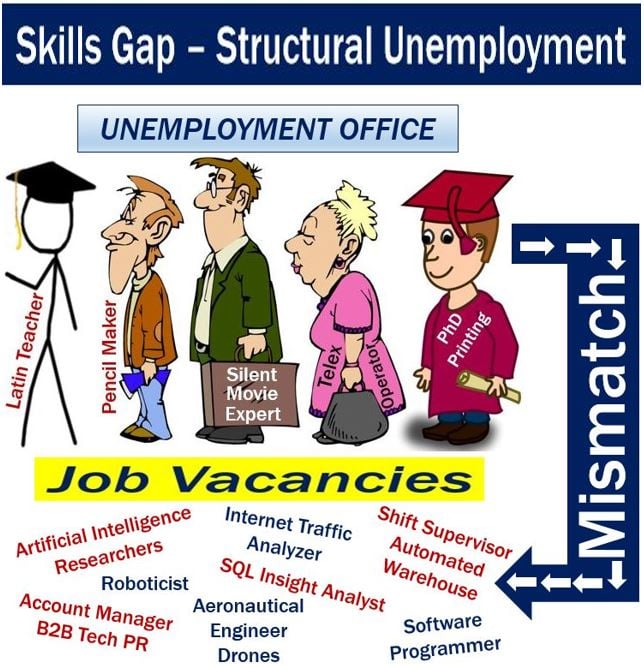

Technological change often means that companies require workers with certain skills, but the ones that are available – unemployed people – do not have those skills.

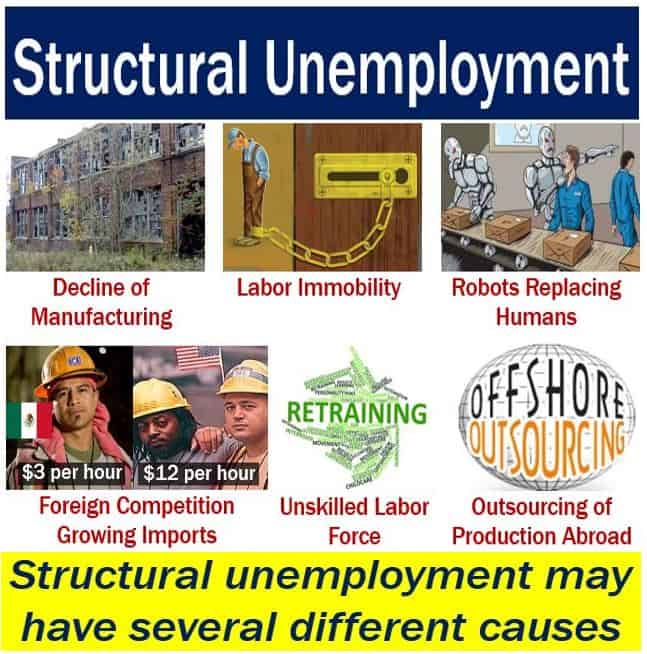

Structural unemployment is one of the most difficult to address. It commonly occurs when there are many job vacancies, but the people looking for work are not qualified for those jobs. It may also be caused by a decline in one or several industries, foreign competition, and the outsourcing of production overseas.

Structural unemployment is one of the most difficult to address. It commonly occurs when there are many job vacancies, but the people looking for work are not qualified for those jobs. It may also be caused by a decline in one or several industries, foreign competition, and the outsourcing of production overseas.

If there are rules that limit labor market flexibility, removing them could help bring down structural unemployment. However, if it is being caused by, for example, the growing use of automation – robots and artificial intelligence – taking people’s jobs, the solution is considerably harder and takes longer to resolve.

Structural unemployment often adds to a high jobless rate a long time after a recession is over. If policymakers ignore the problem, it can lead to even greater levels of natural unemployment.

According to BusinessDictionary.com, structural unemployment is:

“Joblessness caused not by lack of demand, but by changes in demand patterns or obsolescence of technology, and requiring retraining of workers and large investment in new capital equipment.”

Three main causes of structural unemployment

– Technological Advances in an industry that has traditionally employed many workers, or right across the whole economy. For example, in manufacturing, robots have been progressively replacing unskilled workers.

For the unskilled workers to be employed, they need to be trained in computer operations. Then, they can learn how to manage the robots that replaced them.

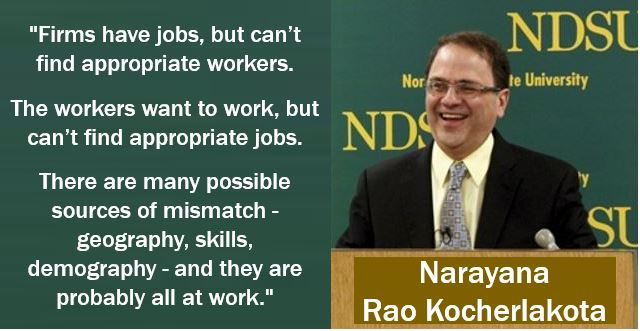

Narayana Kocherlakota, an American economist, was the 12th President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis from October 2008 to December 2015. He is currently the Lionel W. McKenzie Professor of Economics at the University of Rochester, New York. (Image: adapted from minneapolisfed.org)

Narayana Kocherlakota, an American economist, was the 12th President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis from October 2008 to December 2015. He is currently the Lionel W. McKenzie Professor of Economics at the University of Rochester, New York. (Image: adapted from minneapolisfed.org)

– Skills Gap is a mismatch between the skills that current workers in an economy have, and the skills that employers are seeking in their workers.

If a country needs 200,000 skilled robot operators, and there are only 100,000 of them, the job vacancies that currently exist will not be filled.

That is why the US, Canada, UK, Germany and other advanced economies need immigrants – they fill those vacant positions. However, the unskilled domestic workers continue being without jobs.

– Trade Agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) may cause structural unemployment. After Mexico joined NAFTA, many factories either shrank or closed down in the United States and Canada, and relocated to Mexico, where workers are paid a fraction of what their counterparts further north get.

Workers in the higher-paying regions of the trading bloc – the USA and Canada – were laid off.

Structural unemployment – the Internet

Look at the technological changes that have occurred in the newspaper industry. Today, more people in the USA, Western Europe, Japan, Australasia and many other parts of the world read their news online rather than in printed form.

Online newspaper readership has grown dramatically since the turn of the century, while the number of readers of newspapers in printed form has declined significantly.

This has meant that people working in printing, making printers, newspaper delivery boys and girls, and employees working at newsagents and kiosks have been laid off.

In order to get back into the job market in the same field, those laid off people need to get new training.

Unless a skills gap is addressed – by encouraging people to retrain, perhaps offering free courses with incentives – structural unemployment may take a whole generation before it goes away.

Unless a skills gap is addressed – by encouraging people to retrain, perhaps offering free courses with incentives – structural unemployment may take a whole generation before it goes away.

Structural unemployment – global financial crisis

The Global Financial Crisis of 2007/8 and the Great Recession that it caused, raised unemployment levels across North America, Europe and much of the rest of the world.

Did that crisis create structural unemployment? Economists said it probably did, especially for older workers.

In the USA alone, the financial crisis caused the loss of 8.3 million jobs. By the end of 2009, the unemployment rate in many European Union countries had reached nearly twenty percent, and stood at 10.1% in the USA. In Spain, more than one quarter of the adult active population was out of work.

In the United States, almost half of all jobless workers were unemployed for at least six months. As their skills and experience started to become obsolete, structural unemployment set in.

Older workers were more severely affected than their younger counterparts. Younger workers had a greater probability of being unemployed, but those who were did not remain jobless for a long time – in relation to older workers. Either they want back to school, dropped out of the labor force, or accepted jobs that paid less.

Unemployed younger workers during the Great Recession were out of work for an average of 19.9 weeks, which was considerably less than the 44.6 and 43.9 weeks experienced by those aged 55-to-64 and 65+ respectively.

According to The Balance, older workers suffered more for the following reasons:

– Technology: industries, like newspapers, where the Internet and modern technologies reduced workforces, had higher proportions of older workers.

– Training & Education: younger workers are more likely to go back to school or sign up for training programs than their older peers.

– Geographical Mobility: a higher percentage of older workers owned their own homes – they were less able to relocate to find new jobs. With the housing market depressed, selling their homes meant losing a great deal of money.

– Wages: older workers are less likely to accept a new lower-paying job compared to younger ones.

– Agism (UK: Ageism): which means prejudice or discrimination on the grounds of an individual’s age, is a common problem in the job market. Although most employers deny that agism exists within their organizations, it is widespread – ‘old’ workers find it harder to get a new job.

Video – Structural Unemployment

This Marginal Revolution University video explains what structural unemployment is, what may cause it, and why it leads to persistent, long-term joblessness.