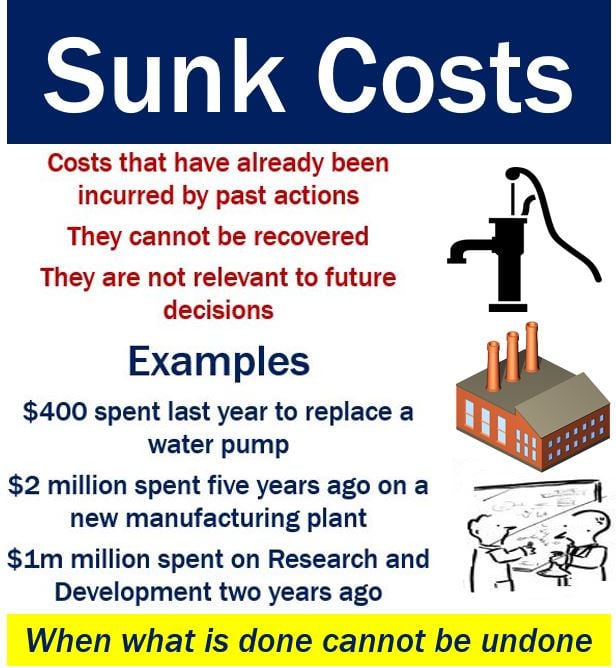

Sunk costs, also known as retrospective costs, refers to money that has been spent or committed and cannot be recovered. In other words, when what you have done cannot be undone – financially speaking.

Sunk costs arise because specialized assets that cannot be readily diverted to other causes are required for some activities. Second-hand markets for sunk costs are therefore limited.

The term contrasts with prospective costs, which are future costs that could be incurred or changed if certain action is taken.

Spending on researching a product idea, advertising, investments in equipment which only produces a particular product, and the development of goods for specific customers are examples of sunk costs – the money committed to them can never be recovered.

Having to commit money that they will never be able to recover may potentially scare off new entrants into a particular market, which makes sunk costs a common barrier to entry.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, the majority of investment expenditures are largely irreversible – “sunk costs that cannot be recovered if market conditions turn out to be worse than expected.”

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, the majority of investment expenditures are largely irreversible – “sunk costs that cannot be recovered if market conditions turn out to be worse than expected.”

The OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) says that all sunk costs are fixed costs, but that not all fixed costs are sunk. Other sources on the Internet say this is not the case.

Wikipedia’s explanation of the term says that they may either be fixed costs – continuous as long as the company is operating and unaffected by volumes of output – or variable costs – dependent on output volume.

According to the OECD, sunk costs are:

“Sunk costs are costs which, once committed, cannot be recovered. Sunk costs arise because some activities require specialized assets that cannot readily be diverted to other uses. Second-hand markets for such assets are therefore limited. Sunk costs are always fixed costs, but not all fixed costs are sunk.”

Sunk costs and decision-making

Business owners, senior managers, and others who making decisions in a commercial enterprise do not include sunk costs in future decisions, because those costs will be the same regardless of what decision they make.

Imagine you own a company that makes sunglasses. Your firm manufactures a basic model – X Shades – that costs $20 and sells for $35 per unit.

You have a choice of selling X Shades and making a $15 profit per unit, or continue production by adding $10 in costs and selling a new luxury model – Super Shades – for $65.

When you are making your decision, you are comparing the $10 additional cost with the $30 additional revenue, and decide to make Super Shades and earn $20 more in profit.

You do not think about how much you spent on your plant’s machinery – the sunk costs – when going through the process of making a decision.

I bought a conference ticket for $500, and later realized that I did not want to go. However, I hated the idea of throwing away the ticket after having spent so much money. So, I ended up paying $1,000 more – a total of $1,500 on the ticket, flights and a 4-day hotel stay. I spent even more money on something I didn’t want! This is a bad case of ‘Sunk Money Fallacy’ – throwing good money after bad. We all do it, and surprisingly often!

I bought a conference ticket for $500, and later realized that I did not want to go. However, I hated the idea of throwing away the ticket after having spent so much money. So, I ended up paying $1,000 more – a total of $1,500 on the ticket, flights and a 4-day hotel stay. I spent even more money on something I didn’t want! This is a bad case of ‘Sunk Money Fallacy’ – throwing good money after bad. We all do it, and surprisingly often!

When sunk costs influence decisions

Even though you should not consider sunk costs when making decisions about the future of your company, history is full of cases of senior management being swayed by how much they had already spent on projects that were proving not to be profitable.

Even today, many managers continue pouring money into unpromising projects because of the huge amounts already invested in the past. They are afraid of ‘losing the investment’ by abandoning the project. This is the Sunk Cost Fallacy at work.

If these senior managers were 100% rational, they would consider those earlier investments as sunk costs – cut their losses – and completely exclude them from their decision-making processes.

Video – What are Sunk Costs?

This Investors Trading Academy video explains what sunk costs are using simple language and easy-to-understand examples. It begins by telling us that the term refers to money that has already been invested in something and cannot be recovered.