A Transition Economy is a country that was once a communist state, and is now becoming a free market economy – changing from communism to capitalism, from central planning to free market.

Since the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Russia, and several other countries abandoned central planning and sought to embrace a free-market system.

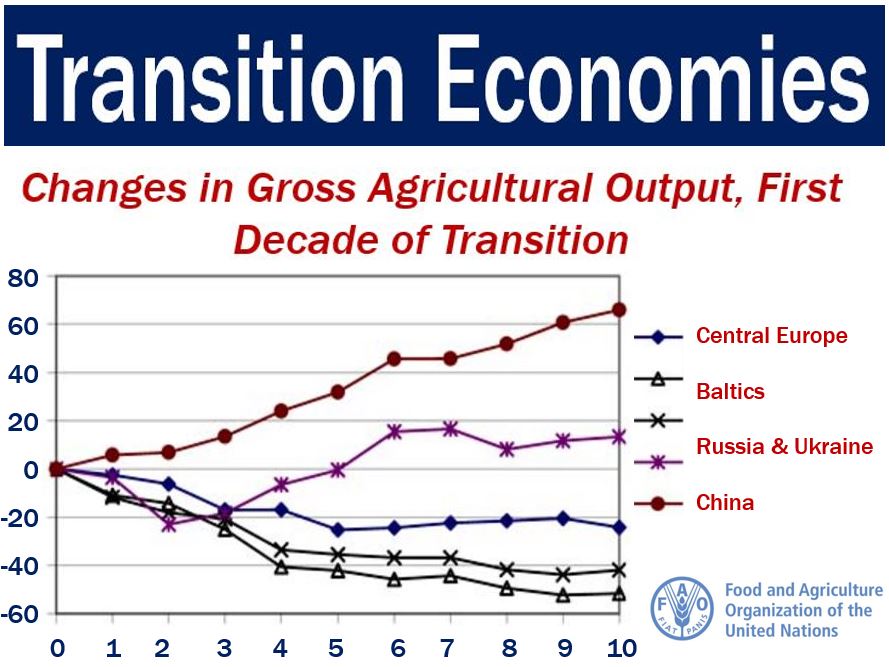

Poland has been a relatively successful transition economy, while Russia has fared less well – the transition economies faced some moderate to severe difficulties.

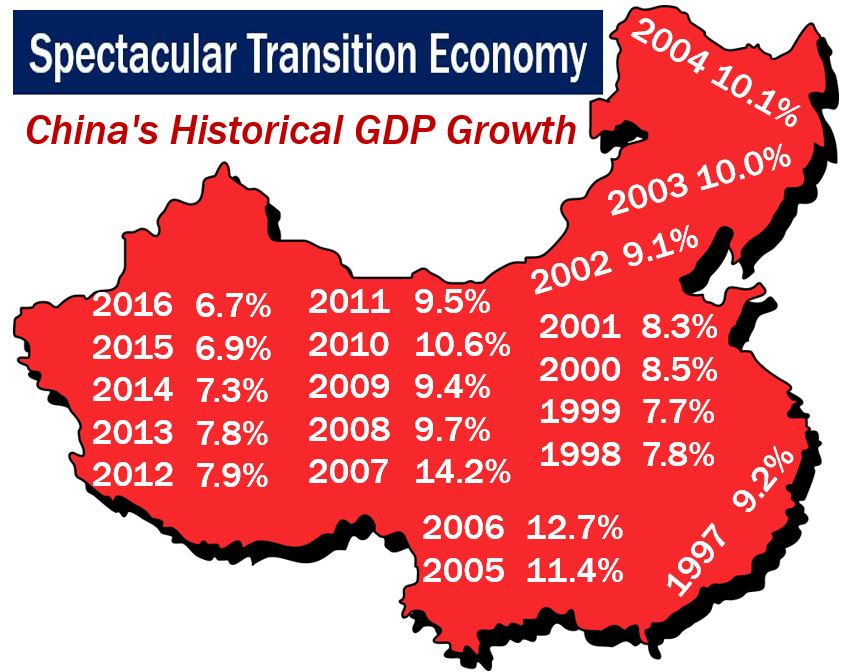

China’s transition from the rigid communist system of Chairman Mao (Mao Zedong or Mao tse-tung), to the mixed economy it is today has been spectacular. In little more than three decades, China leaped from being nowhere near the ten largest economies in the world to the second biggest today.

According to Dictionary.Cambridge.com, a transition economy is:

“An economy that is changing from being one under government control to being a market economy (= one in which companies are not controlled by the government).”

Structural changes in a transition economy

A transition economy undergoes a series of structural reforms and transformation aimed at developing market-based institutions.

Rather than being set by a central planning organization, prices are freed and determined by market forces; this process is known as economic liberalization.

Trade barriers are removed and there is a push to privatize most of the state-owned companies. A financial sector is created to allow the movement of private capital.

During the process of change, the functional restructuring of state institutions in the transition economy allows it to turn from being a provider of economic growth to an enabler, with the private sector as its driving force.

Worsening unemployment

Rising unemployment has been a feature of every transition economy, as newly-privatized businesses tried to improve efficiency.

When they were communist countries, virtually all their companies employed considerably more workers than they really needed. As private commercial enterprises entered the market, one of the first things to be cut back were labor costs.

As trade barriers were lifted, the newly-established private companies had to compete with the ultra-efficient multinationals of North America, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea and Australasia. Many were unable to cope and were driven out of the market, resulting in the loss of jobs for tens of millions of workers.

During the period of transition, the state bureaucracy – which had been massive – was scaled back. Millions of state employees lost their jobs.

Inflation in a transition economy

In a centrally-planned economy, prices are controlled by the government. When these price controls were removed, every transition economy experienced rising price inflation.

The newly-privatized companies had to determine their own prices, which they mainly calculated by responding to the economic forces of supply and demand and the true costs of production.

Some entrepreneurs tried to profit from the new situation and raised their prices excessively.

The average annual inflation rate in the transition economies during the 1990s was approximately 20%.

Since the beginning of this century, inflation rates in Eastern Europe have moved much closer to those found in Western Europe and the other advanced economies across the world.

Corruption in the transition economies

Corruption in the communist states of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union was widespread. During the early years of transition, many corrupt officials and bureaucrats became corrupt directors of newly-privatized companies.

This corrupt environment, a number of economists believe, undermined the effective introduction of market reforms.

With corruption infecting vast parts of senior management, many goods were poorly made and sold in illegal or unregulated markets. Criminal gangs emerged, filling the giant vacuum left by the former communist regimes.

Regarding the lack of infrastructure, Economics Online writes:

“The transition economies also suffered from a lack of real capital, such as new technology, which is required to produce efficiently. This was partly because of the limited development of financial markets, and because there was little inward investment from foreign investors.”

“Clearly, this has changed as the transition economies have reformed, and joined the global market, which has encouraged inward investment (Foreign Direct Investment – FDI) from around the world.”

Video – What is a Transition Economy?

This video, from our sister YouTube Channel – Marketing Business Network – explains what a “Transition Economy” is using easy-to-understand language and examples: