Wage drift is the difference between basic salaries and total earnings. Bonuses, overtime payments, performance-related pay, and profit share all contribute to the wage drift. It is the result of **ad hoc arrangements that distort the expected outcomes from wage settlements that are agreed nationally.

** ad hoc means not planned before it happens; made for a particular purpose or need.

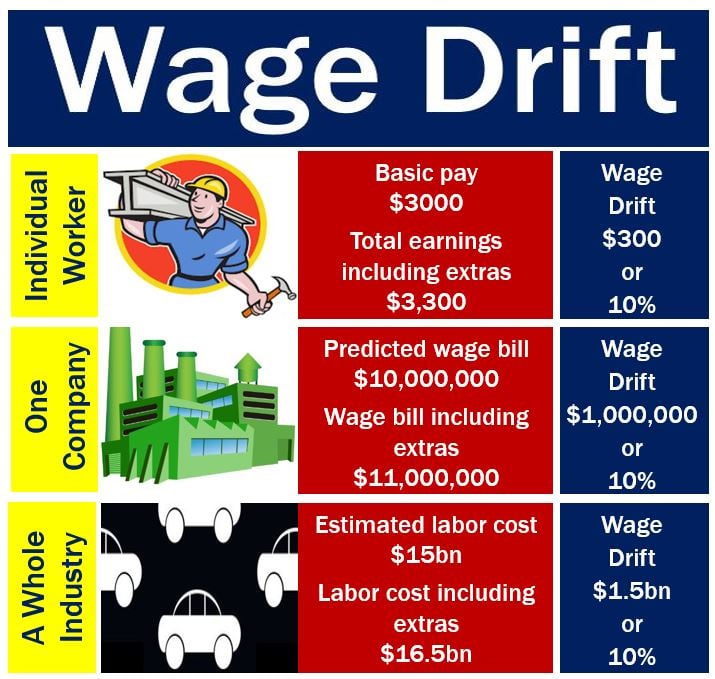

The term may apply to either an individual worker, a whole company, or an entire industry:

– Industry: it may refer to the tendency for the average amount of money paid to employees to rise more rapidly than the official wage rates for that industry – usually a figure agreed during collective bargaining procedures between unions, employers and workers.

– The Individual: the difference between one person’s basic pay and his or her total compensation, which includes overtime pay, pensions and other financial benefits.

– The Company: the difference between the rates negotiated by a firm and total money actually paid to its workers over a specific period. If the expected wage bill for a three-month period (quarter) is $10,000,000, but it ends up being $11,000,000, after including overtime and other items, the wage drift for that quarter was $1,000,000 or 10%.

Wage drift is the difference between the basic wage bill and the total earnings bill, which includes overtime, performance bonuses, profit share, and other financial incentives or benefits.

Wage drift is the difference between the basic wage bill and the total earnings bill, which includes overtime, performance bonuses, profit share, and other financial incentives or benefits.

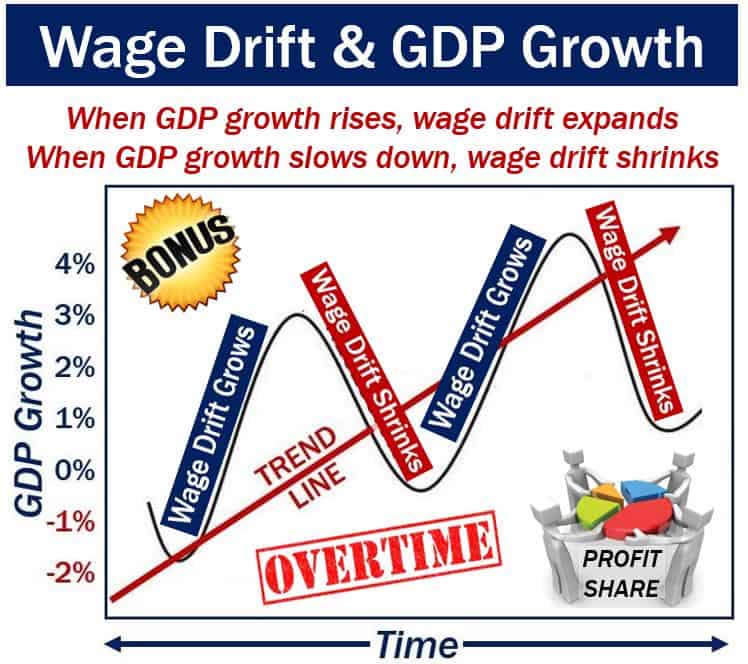

Wage drift and GDP growth rates

Wage drift generally increases during periods of strong GDP (gross domestic product) growth, and falls when growth slows down or the economy shrinks.

During a recession, for example, the amount of overtime that workers do is considerably less, as are profit share payments and other financial benefits.

For the human resource professional, wage drift poses a real problem when attempting to precisely predict and fix wages. Most of the factors that cause wages to ‘drift’ are beyond the control of the recognized procedure of negotiating workers’ pay.

When unions, workers and employers are negotiating wage rates, nobody can 100%-precisely predict how much overtime will be required at any given week, month or moment.

When business is good, companies get more new and unexpected orders, in order to meet them they offer their workers attractive overtime rates. When business activity slows down, however, the opposite happens.

When business is good, companies get more new and unexpected orders, in order to meet them they offer their workers attractive overtime rates. When business activity slows down, however, the opposite happens.

The mechanism of wage drift may occur in one of two possible ways:

– Higher Earnings: when workers earn more than their agreed totals (their basic pay), their earnings between two successive raises may increase without any change in the amount of work they do.

– Underutilized Labor: earnings may remain the same, but workers’ labor may be underutilized.

“When earnings increase faster than labor inputs, unit labor cost to the company will increase irrespective of the cause being a wage drift or not.”

Is wage drift a problem?

Wage drift can be a cause of rising inflation, especially if increases in earnings are not matched by an equivalent rise in worker productivity.

If workers earn 10% more than was predicted from negotiated wage settlements, but total production remains the same, there will be more money chasing the same number of goods. When too much money chases too few goods, prices rise.

Wage drift was a major cause inflation in the United Kingdom during the 1960s. During that time, it became apparent that earnings were rising much faster than might be expected from the formal increases in pay agreed through multi-employer negotiated industry agreements.

Regarding the UK in the 1960s, OxfordReference.com writes:

“The source of the increase in earnings was the growth in informal workplace bargaining and poorly managed incentive schemes that allowed workers to raise their earnings well above the agreed rates at industry level.”

“An element of wage drift will emerge in any system of centralized pay determination and is an important feature of the labor market in many different national economies.”