Overall, the gender wage gap in the UK has been closing over the last 20 years. Currently, on average, women earn about 18 percent per hour less than men – this compares with 28 percent in 1993 and 23 percent in 2003.

However, inside the overall trend, there are some stark contrasts, according to a new report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

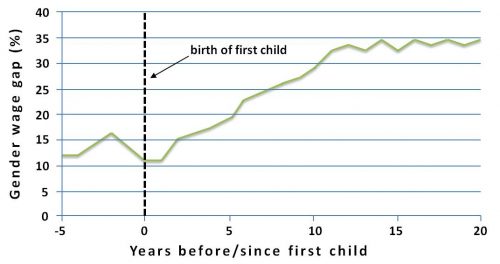

The most striking pattern is what happens to the gender wage gap once women start having children.

The UK’s gender wage gap is smaller when comparing women before they are mothers with their male counterparts, and then it gradually widens bit by bit every year for about 12 years after they have their first child. At this point, women receive 33 percent less pay per hour than men.

While the UK’s average gender wage gap has been closing over the last 20 years, women today still earn on average 18 percent less per hour than men.

While the UK’s average gender wage gap has been closing over the last 20 years, women today still earn on average 18 percent less per hour than men.

It appears the reason the gender wage gap widens once children come along is because wage growth enjoyed by full-time workers tends to bypass women who reduce hours after having children.

Women who take time out of paid work altogether and return to the labour market also miss out on wage growth.

The IFS raise the possibility that returning or part-time working mothers miss out on promotion, or they gather less experience of the labour market.

Gap has not closed among the higher educated

The report – sponsored by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation – also shows that the closing of the average gap over the last 20 years has not occurred among graduates and people with A-levels – but mainly in the less-educated.

But, on the other hand, the fact education levels have risen faster among women than men have also helped close the gender wage gap.

Before women start having children, the employment rates of men and women are largely similar. But once children start to come along, rates start to diverge, and they diverge at different rates depending on education.

Among graduate women, employment rates drop by around 16 percentage points between the year before and the year after their child is born.

For women with A levels the rates drop by 19 percentage points, and for women with GCSEs they drop by around 33 percentage points.

Women’s employment rates remain lower than men’s for at least 20 years after childbirth.

Meanwhile for men, having children barely affects their rates of employment.

Need to understand gender wage gap before we can tackle it

The IFS also calculated the “wage penalty” for women taking time out of paid work to have children is on average 2 percent per year spent not working.

Thus, for example, women who take a 2-year break to have children earn on average 4 percent less when they return than what they would have earned if they had not taken the break.

The lack of progression for women who reduce hours after having children

The lack of progression for women who reduce hours after having children

needs to be understood if the gender wage gap is to be tackled properly, say the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS). They found the gap widens yearly after children come along. Data from: IFS report.

One of the report authors, Robert Joyce, Associate Director at IFS, says:

“The gap between the hourly pay of higher-educated men and women has not closed at all in the last 20 years. The reduction in the overall gender wage gap has been the result of more women becoming highly educated, and a decline in the wage gap among the lowest-educated.”

In her first statement as Prime Minister, Theresa May said, “If you’re a woman, you will earn less than a man.” She said this was one of the many “injustices” that she and her new government intended to tackle “to make Britain a country that works for everyone.”

The IFS report highlights some of the complexity surrounding this issue. Joyce suggests that one of the key challenges to tackling the gender pay gap is going to be understanding the lack of progression for women who reduce their hours – the lower pay they earn in such jobs is not due to switching from full-time work.