The discovery of a half-billion year old brain is helping scientists determine how heads first evolved in early animals on Earth during the Cambrian Explosion, a period of crucial transformation of life forms, a researcher from the University of Cambridge said.

The latest finding identifies a key point in the evolutionary transition from soft to hard bodies in the early ancestors of arthropods – invertebrate animals having an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and jointed appendages such as insects, crustaceans and spiders.

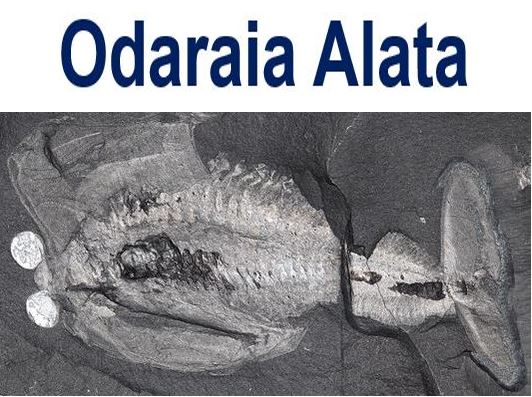

Dr. Javier Ortega-Hernández, a postdoctoral researcher from Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences, who wrote about the discovery in the journal Current Biology, looked at two types of arthropod ancestors – a soft-bodied trilobite (a fossil marine arthropod that was abundant during the Palaeozoic era) and Odaraia alata, a weird-looking creature that looked like a submarine.

A submarine-like arthropod – Odaria alata – from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. (Image: Cambridge)

He found that the hard plate (anterior sclerite) and eye-like features at the front part of their bodies were connected via nerve traces originating from the front part of their brains, which corresponds with how arthropods today see things.

The new results also allowed comparisons with anomalocaridids, a group of large aquatic predators of the period. Dr. Ortega-Hernández found key similarities between the anterior sclerite and a plate located on the top of the head of anomalocaridids, suggesting that the different species shared a common origin.

Despite anomalocaridids being early ancestors of arthropods, their bodies are actually quite different.

Thanks to the amazingly well-preserved brains in these fossil specimens, researchers can now recognise the anterior sclerite as a bridge between the anomalocaridids’ head and that of the jointed arthropods we see today.

When soft-bodied creatures became hard-bodied

Dr Ortega-Hernández said:

“The anterior sclerite has been lost in modern arthropods, as it most likely fused with other parts of the head during the evolutionary history of the group.”

“What we’re seeing in these fossils is one of the major transitional steps between soft-bodied worm-like creatures and arthropods with hard exoskeletons and jointed limbs – this is a period of crucial transformation.”

Dr. Ortega-Hernández noticed that the bright spots at the front of the bodies, which are, in fact, simple photoreceptors, are embedded into the anterior sclerite.

The photoreceptors connect to the front of the fossilised brain, as do those in modern arthropods.

These ancient brains probably processed data much in the say way those of modern arthropods do, and were essential for interacting with the environment, getting away from predators, and finding food.

The Cambrian Explosion

The Cambrian Explosion, also known as the Cambrian Radiation, was a relatively brief evolutionary event that started about 542 million years ago in the Cambrian Period, during which the majority of major animal phyla appeared, according to fossil records.

Arthropods with hard exoskeletons and jointed limbs began appearing about 500 million years ago, during the Cambrian Explosion.

Before this period, most living things on Earth were jelly fish or algae-like creatures with soft bodies.

These fossils, from the collections of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, and the Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., came from one of the richest fossil sources from the period – the Burgess Shale in Western Canada.

One of the most difficult tasks for scientists is determining how brains evolved, because they are made of soft tissues (mainly fatty-like substances) that do not fossilise well.

Even in the Burgess Shale, where relatively lots of fossilised samples have been unearthed, finding brain tissue is extremely uncommon.

Dr. Ortega-Hernández explained:

“Heads have become more complex over time. But what we’re seeing here is an answer to the question of how arthropods changed their bodies from soft to hard.”

“It gives us an improved understanding of the origins and complex evolutionary history of this highly successful group.”

The study was financed by Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

In a separate study, also performed at the University of Cambridge, by Dr. Martin Smith, a Junior Research Fellow, a new species of Penis Worm was discovered at Burgess Shale from 500 million years ago. It could turn its mouth inside out, revealing a teeth-lined throat resembling a cheese grater.

Reference: Javier Ortega-Hernánde. “Homology of Head Sclerites in Burgess Shale Euarthropods,” Current Biology. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.034.