The Irish people come from all over the place, as far afield as the Middle East, Southern Europe and Eurasia, according to the ancient genomes of a woman and three men. Scientists mapped the DNA of three Irish male adults from the Bronze Age, about 4,000 years ago, and a female farmer who lived approximately 5,200 years ago.

Geneticists at Trinity College Dublin and Queen’s University Belfast explained in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences how they sequenced the first genomes of ancient Irish humans and what they found.

The study’s findings are already answering a number of questions regarding the origins of the Irish population, as well as certain aspects of their culture.

The bones of one of the Bronze Age men. (Image: Trinity College Dublin)

The bones of one of the Bronze Age men. (Image: Trinity College Dublin)

The ancient DNA sequencing suggests that humans probably migrated to the British Isles in at least two large movements, firstly from the Middle East and later from Eastern Europe.

These two mass migrations coincided with technological advances – from hunter gatherer to farming and from the age of stone to the age of metal – suggesting that these migrants brought these skills with them to the British Isles.

Ireland’s genetic ‘intriguing’

Study leader, Dan Bradley, Professor of Population Genetics in Trinity College Dublin, and colleagues described Ireland’s genetics as ‘intriguing’.

It lies at the edge of a number of European genetic gradients, with the world’s maxima for variants that code for lactose intolerance – the western European Y chromosome type – and several major genetic diseases, including cystic fibrosis, which causes the production of abnormally thick mucus that leads to the blockage of the pancreatic ducts, intestines and bronchi and often results in respiratory infection, and the blood disorder haemochromatosis that causes the body to retain too much iron.

A reconstruction of the skull of the Ballynahatty Neolithic woman, by Elizabeth Black. Her genes tell us she had brown eyes and black hair and was closely related to modern Spanish and Sardinians. (Image credit: Barrie Hartwell)

A reconstruction of the skull of the Ballynahatty Neolithic woman, by Elizabeth Black. Her genes tell us she had brown eyes and black hair and was closely related to modern Spanish and Sardinians. (Image credit: Barrie Hartwell)

A genetic time machine

Scientists have long been unable to explain the origins of this heritage. To be able to get into the meat and bones of what happened in genetic history, nothing can beat a direct look at the past itself, i.e. to sequence the genomes directly from ancient people by travelling into a kind of genetic time machine.

Migration has been a hot topic for British and Irish archaeologists for a very long time. None of them is sure whether the major lifestyle changes that occurred in the British Isles, such as the transition from hunter-gatherer to agriculture, and later from stone to using metal, were due to an internal or domestic evolution, or whether immigrants from outside made these changes happen.

The ancient Irish genomes of the three men and the female farmer each show clear evidence of massive migration. The researchers discovered that early Irish farmers have a majority ancestry originating ultimately from the Middle East, where farming was invented.

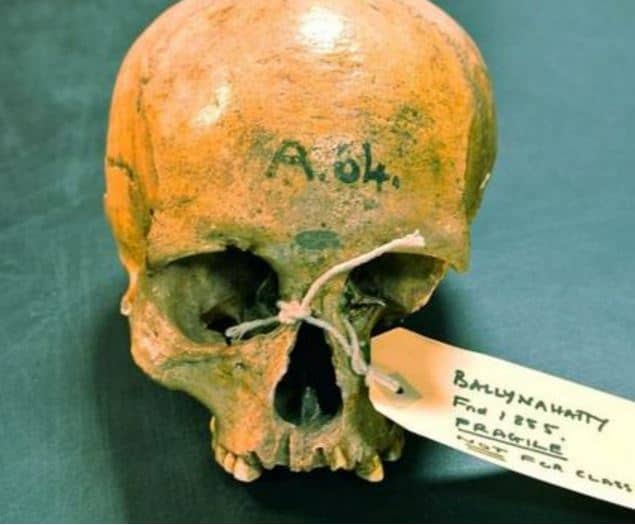

The skull of the Ballynahatty woman, who was excavated near Belfast in 1855, remained in a Neolithic tomb chamber for over 5,000 years. (Image Credit: Daniel Bradley, Trinity College Dublin)

The skull of the Ballynahatty woman, who was excavated near Belfast in 1855, remained in a Neolithic tomb chamber for over 5,000 years. (Image Credit: Daniel Bradley, Trinity College Dublin)

The three Bronze Age men’s genomes are different. They show around one third of their ancestry originating from ancient sources in the Pontic Steppe, a large area extending from the northern part of the Black Sea eastward to northwest Kazakhstan.

Prof. Bradley said:

“There was a great wave of genome change that swept into Europe from above the Black Sea into Bronze Age Europe and we now know it washed all the way to the shores of its most westerly island, and this degree of genetic change invites the possibility of other associated changes, perhaps even the introduction of language ancestral to western Celtic tongues.”

Dr. Eileen Murphy, a Senior Lecturer in Osteoarchaeology (concerned with the study of human and animal remains from archaeological sites) at Queen’s University Belfast, said:

“It is clear that this project has demonstrated what a powerful tool ancient DNA analysis can provide in answering questions which have long perplexed academics regarding the origins of the Irish.”

The three Bronze Age men were unearthed in Rathlin Island and the Neolithic female farmer in Ballynahatty.

The three Bronze Age men were unearthed in Rathlin Island and the Neolithic female farmer in Ballynahatty.

Irish genome a mixture from lots of places

Early farmers in Ireland had brown eyes and black hair, much like the people in southern Europe. The genetic variants found in the three Bronze Age males from Rathlin Island, the northernmost point of Northern Ireland, had the most common Irish Y chromosome type, blue eye alleles and the important variant for haemochromatosis.

The C282Y mutation, associated with haemochromatosis, is so common among the people in Ireland, or those elsewhere in the world of Irish descent, that it is often called a Celtic disease. This discovery is the first to identify a major disease variant in prehistory.

The Neolithic woman was found to be most closely related to modern Sardinians and Spanish, while the three Rathlin men were genetically close to modern Welsh, Scottish and Irish. The scientists say the topic of future study will be how the genomes have changed since the Bronze Age.

PhD Researcher in Genetics at Trinity, Lara Cassidy, said:

“Genetic affinity is strongest between the Bronze Age genomes and modern Irish, Scottish and Welsh, suggesting establishment of central attributes of the insular Celtic genome some 4,000 years ago.”

Reference: “Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome,” James Mallory, Lara M. Cassidy, Rui Martiniano, Eileen M. Murphy, Barrie Hartwell, Matthew D. Teasdale and Daniel G. Bradley. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 28th December, 2015. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1518445113.

Video – Reading the Past in Ancient Irish Genomes

Lara Cassidy, Prof. Dan Bradley and Dr. Eileen Murphy talk about the origins of the Irish people after sequencing the DNA of four people who lived several thousands of years ago.