For Life on Mars to have existed at some time during its existence is looking increasingly more likely, says a team of researchers from Russia, Canada, France, the United States, and the United Kingdom. The scientists say they have discovered ‘halos’ on the Red Planet’s surface that lengthen the time when life on Mars – life as we know it – may have existed.

These halos are lighter-toned rock that surrounds fractures. The halo areas of the rock contain elevated concentrations of silica.

The halos, which have been discovered in the Gale crater, suggest that the Red Planet had liquid water for significantly longer than scientists had previously thought.

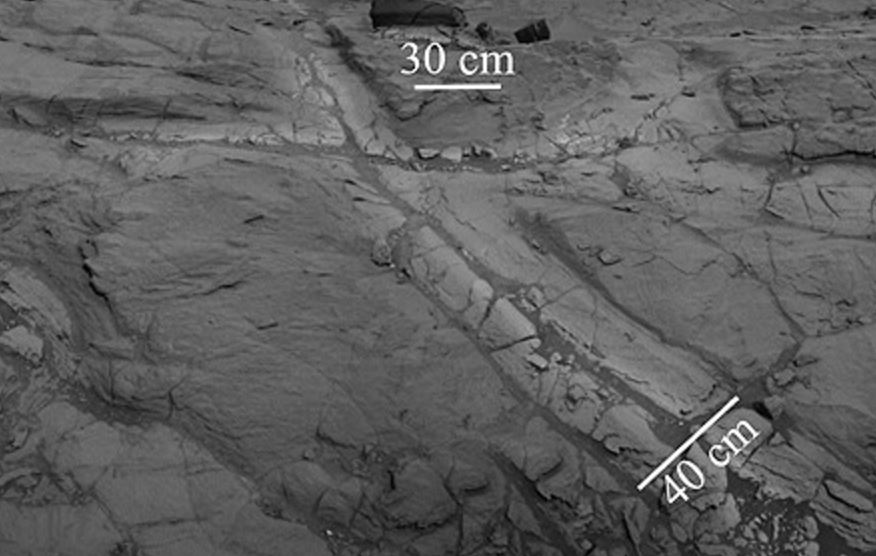

The Los Alamos National Laboratory writes: “A mosaic of images from the navigation cameras on the NASA Curiosity rover shows “halos” of lighter-toned bedrock around fractures. These halos comprise high concentrations of silica and indicate that liquid groundwater flowed through the rocks in Gale crater longer than previously believed.” (Image: lanl.gov. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The Los Alamos National Laboratory writes: “A mosaic of images from the navigation cameras on the NASA Curiosity rover shows “halos” of lighter-toned bedrock around fractures. These halos comprise high concentrations of silica and indicate that liquid groundwater flowed through the rocks in Gale crater longer than previously believed.” (Image: lanl.gov. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Jens Frydenvang, from the Los Alamos National Laboratory in the USA, and the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, and colleagues wrote about their study and findings in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, in an article published on May 30th, 2017, titled ‘Diagenetic silica enrichment and late-stage groundwater activity in Gale crater, Mars‘.

The scientists gathered and analyzed data from NASA Curiosity rover’s science payload. They found that at these halos’ centerlines, levels of silica are very high. The scientists believe that silica migrated from the very old sedimentary bedrock into the much younger overlying rock.

Probability of life on Mars now greater

Frydenvang, who was lead author, said:

“The goal of NASA’s Curiosity rover mission has been to find out if Mars was ever habitable, and it has been very successful in showing that Gale crater once held a lake with water that we would even have been able to drink, but we still don’t know how long this habitable environment endured.”

“What this finding tells us is that, even when the lake eventually evaporated, substantial amounts of groundwater were present for much longer than we previously thought – thus further expanding the window for when life might have existed on Mars.”

Once the Gale crater – artist’s impression above – was full of water. There was sunlight, oxygen and moderate temperatures. It was an ideal environment for life to have existed. (Image: massarate.ma)

Once the Gale crater – artist’s impression above – was full of water. There was sunlight, oxygen and moderate temperatures. It was an ideal environment for life to have existed. (Image: massarate.ma)

The authors said they did not know whether this groundwater may have sustained life as we know it. However, the findings from this new study support the findings of another study, which discovered boron on Mars for the first time.

The findings from the two studies suggest that perhaps there was once the potential for long-term habitable groundwater on the Red Planet – in other words, perhaps there was once life on Mars.

Curiosity’s suite of instruments, including its ChemCam instrument, analyzed the halos. ChemCam stands for Chemistry and Camera.

Over a period of 1,700 Martian days, known scientifically as sols, Curiosity has traveled over 10 miles (16 km). It has traveled from the bottom of Gale crater to a half-way point up Mount Sharp, which is in the center of the crater.

The authors have been examining all the ChemCam data in their quest to get a more complete picture of the Red Planet’s geological history.

The elevated silica levels in the halos were discovered approximately 20 to 30 meters high, near to a rock-layer of ancient lake sediments – silica concentration in those sediments is high.

Frydenvang added:

“This tells us that the silica found in halos in younger rocks close by was likely remobilized from the old sedimentary rocks by water flowing through the fractures.”

Some of the halo-containing rocks were deposited by wind, most likely as dunes. These types of dunes could only exist after all the lake’s water had dried up.

The scientists are convinced that groundwater was still flowing within the rocks considerably more recently than previously thought, because the halos that were present in the rocks were formed long after the lake dried up.

Los Alamos scientists: “halos” on #Mars could mean a longer life-friendly past. #ChemCam @NASAJPL @CNES @MarsCuriosity @SarcasticRover pic.twitter.com/8QaQX4gtTE

— Los Alamos Lab (@LosAlamosNatLab) May 30, 2017