The mass extinction that rapidly killed off the non-avian dinosaurs was just as deadly for life forms that existed in the polar regions as elsewhere on Earth, a new study involving over 6,000 marine fossils from the Antarctic has shown.

The mass extinction event that occurred about 66 million years ago is known as the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, or the Cretaceous–Tertiary (K–T) extinction. About three-quarters of all plant and animal species on Earth became extinct.

The findings of this latest study, carried out by scientists from the University of Leeds and the British Antarctic Survey, both in the UK, and published in the prestigious journal Nature Communicaitons, go against what most experts had thought.

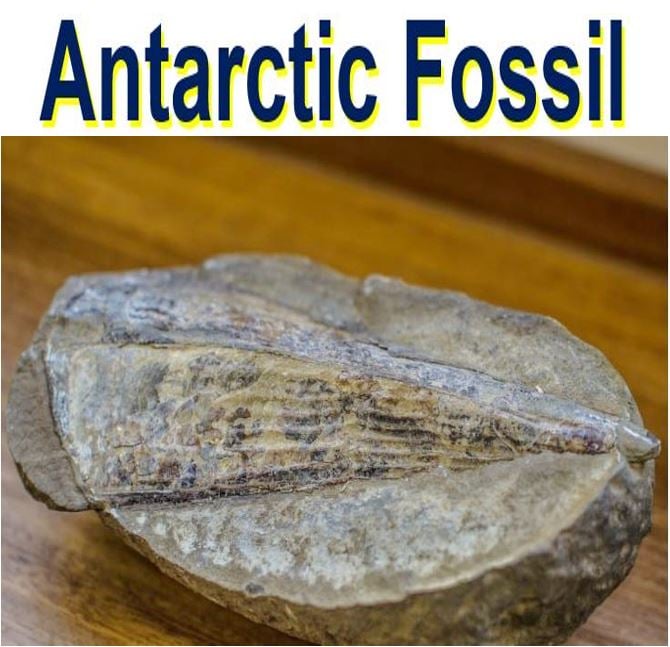

One of the fossils studied from Seymour Island. Over 6,000 fossils were examined in this study. (Image: bas.ac.uk)

One of the fossils studied from Seymour Island. Over 6,000 fossils were examined in this study. (Image: bas.ac.uk)

Southernmost species also killed off suddenly

Before this study, scientists believed that life forms living in the southernmost regions of Earth would have been in a less vulnerable position during the Cretaceous–Tertiary (K–T) extinction, compared to those elsewhere on the planet.

Lead author, James Witts, a PhD student in Leeds University’s School of Earth and Environment, and colleagues said their research involved a six-year process of identifying over 6,000 marine fossils that date back to 65 million to 69 million years ago.

The specimens had been excavated by scientists from the British Antarctic Survey on Seymour Island in the Antarctic Peninsula and the University of Leeds.

This is one of the most extensive collections of marine fossils of this age globally. It includes several different species, from clams and small snails that lived on the sea floor, to the big and unusual marine creatures that swam in the surface waters of the ocean.

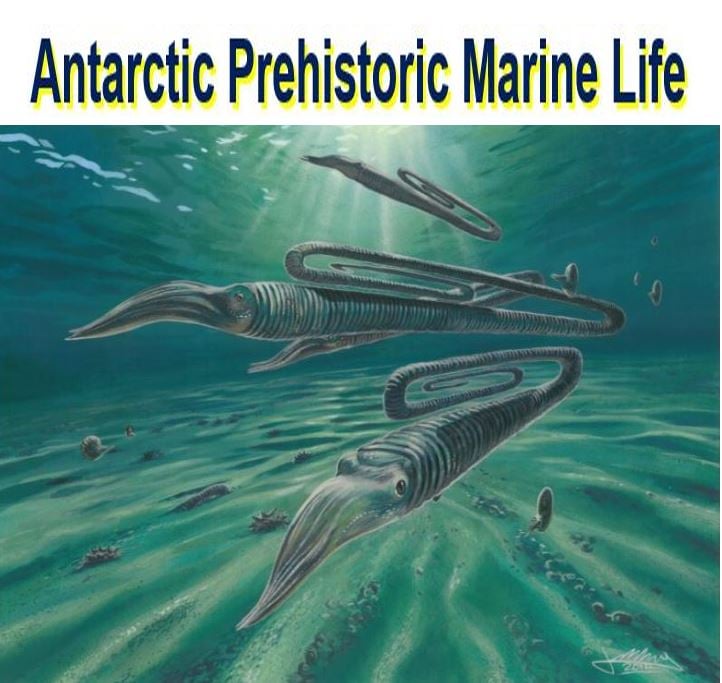

An artist’s rendition of a typical Cretaceous marine environment in Antarctica, including the paperclip-shaped ‘heteromorph’ ammonite. (Image: leeds.ac.uk. Credit: James McKay)

An artist’s rendition of a typical Cretaceous marine environment in Antarctica, including the paperclip-shaped ‘heteromorph’ ammonite. (Image: leeds.ac.uk. Credit: James McKay)

These include the ammonite Diplomoceras – a distant relative of today’s octopus and squid – which had a paperclip-shaped shell that could reach 2 metres in length, and massive marine reptiles such as Mosasaurus, as featured in the movie Jurassic World.

The scientists grouped the fossils by age and found there was a significant – 65% to 70% – reduction in the numbers of species living in the Antarctic region sixty-six million years ago. This was exactly when the dinosaurs and several other groups of organisms across the world became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period.

Antarctic experienced an abrupt reduction

Mr. Witts said:

“Our research essentially shows that one day everything was fine – the Antarctic had a thriving and diverse marine community – and the next, it wasn’t. Clearly, a very sudden and catastrophic event had occurred on Earth.”

“This is the strongest evidence from fossils that the main driver of this extinction event was the after-effects of a huge asteroid impact, rather than a slower decline caused by natural changes to the climate or by severe volcanism stressing global environments.”

The authors say their study is the first to suggest that the mass extinction event that killed off the non-avian dinosaurs was just as devastating, rapid and severe in the polar regions as elsewhere on Earth.

Scientists had believed that life forms living near the Poles were far enough away from what caused the extinction to be severely affected – whether this was due to extreme volcanism in the Deccan volcanic province in India, or the killer asteroid that crashed in the Gulf of Mexico, where a massive buried impact crater is found today.

The killer-asteroid, which scientists believe was most likely the cause of the mass extinction 66 million years ago and wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs, caused the same degree of species extinctions in the polar regions as elsewhere on Earth, this new study suggests.

The killer-asteroid, which scientists believe was most likely the cause of the mass extinction 66 million years ago and wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs, caused the same degree of species extinctions in the polar regions as elsewhere on Earth, this new study suggests.

Experts had also thought that the plants and animals of the polar regions were more resilient to global climatic changes linked to an asteroid impact, because they lived in environments that were always strongly seasonal. Any organism that lives very near the poles has to learn to survive in six months of darkness, and with an extremely irregular food supply.

Co-author, Prof. Jane Francis, from the British Antarctic Survey, said:

“These Antarctic rocks contain a truly exceptional assemblage of fossils that have yielded new and surprising information about the evolution of life 66 million years ago. Even the animals that lived at the ends of the Earth close to the South Pole were not safe from the devastating effects of the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous Period.”

Most fossils are of marine creatures

Some studies have suggested that the dinosaurs’ and other groups’ downfall was gradual. However, many scientists point out that dinosaur fossil records are very patchy, and in no way can compete with marine fossils in terms of biodiversity and quantity.

Mosasaurus was a huge carnivorous aquatic lizard that existed until 66 million years ago. A Mosasaurus fossil was examined during the study. (Image: dinosaurpictures.org)

Mosasaurus was a huge carnivorous aquatic lizard that existed until 66 million years ago. A Mosasaurus fossil was examined during the study. (Image: dinosaurpictures.org)

Mr. Witts said:

“Most fossils are formed in marine environments, where it is easy for sediment to accumulate rapidly and bury parts of animals, such as bones, or bodies of creatures with a hard shell. For a dinosaur or other land animal to become fossilised, a series of favourable events are needed, such as for bones to fall into stagnant water and be buried rapidly to prevent decomposition, or be washed out to sea by rivers.”

“This means that marine fossils are generally much more abundant. They can give us a much larger data set for studying how ecosystems and biodiversity change over time in the geological past, and enable us to draw robust conclusions about events during periods of rapid environmental change, like mass extinctions.”

In an Abstract that precedes and describes the main article, the authors wrote:

“We show that the extinction was rapid and severe in Antarctica, with no significant biotic decline during the latest Cretaceous, contrary to previous studies.”

“These data are consistent with a catastrophic driver for the extinction, such as bolide impact, rather than a significant contribution from Deccan Traps volcanism during the late Maastrichtian.”

Citation: “Macrofossil evidence for a rapid and severe Cretaceous–Paleogene mass extinction in Antarctica,” Jane E. Francis, James D. Witts, Rowan J. Whittle, J. Alistair Crame, Robert J. Newton, Paul B. Wignall & Vanessa C. Bowman. Nature Communications 7, Article number: 11738. 26 May 2016. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms11738.

Video – Hunting for fossils in the Antarctic

In this University of Leeds video, James Witt talks about the study which found that life forms in the Antarctic region suffered as severely during the mass extinction of 66 million years ago as other organisms across the planet.