Scientists at MIT have created a cheap, portable sensor that can tell you when meat or fish in your fridge or at the grocery store is safe to eat by detecting the gases emitted when it starts to rot. You would be able to take this device to the shops and decide for yourself what is safe to consume.

Timothy Swager, the John D. MacArthur Professor of Chemistry at MIT, says the sensor consists of chemically-modified carbon nanotubes. They could be deployed in “smart packaging” that would provide much more accurate, relevant and reliable data than the current system of displaying an expiry date.

The sensor would also significantly reduce food waste. “People are constantly throwing things out that probably aren’t bad,” said Prof. Swager.

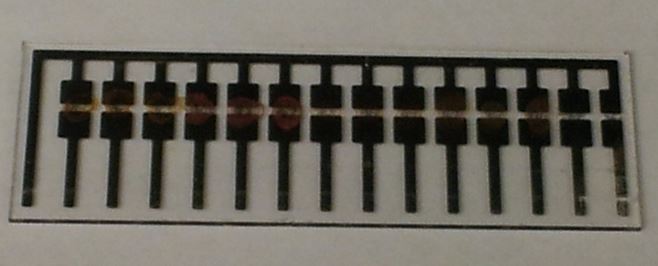

The MIT rotting meat sensor device, based on modified carbon nanotubes, can detect amines produced by decaying meat. (Image: Sophie Liu)

Senior author, Prof. Swager and colleagues wrote about the new sensor in the academic journal Angewandte Chemie (citation below). Graduate student Sophie Liu is the paper’s lead author. Other authors include postdoc Graham Sazama and lab technician Alexander Petty.

The meat sensor is similar to other carbon nanotube devices that Swager’s laboratory has developed in recent years, including one that can tell you how ripe a fruit is.

Measuring electrical current in carbon nanotubes

They all work on the same principle: Carbon nanotubes can be chemically modified so that their ability to carry an electric current alters in the presence of a specific gas.

For the device that can sense rotting meat or fish, they modified the carbon nanotubes with metalloporphyrins (metal-containing compounds), which contain a central metal atom bound to several nitrogen-containing rings.

Hemoglobin is a metalloporphyrin with iron as the central atom.

Metalloporphyrin with cobalt

For the new sensor, the scientists used a metalloporphyrin with cobalt at its center. Metalloporphyrins are very good at binding to amines (nitrogen-containing organic compounds derived from ammonia).

The researchers were particularly interested in the so-called biogenic amines, such as cadaverine and putrescine, which are produced when meat or fish decays.

When the cobalt-containing porphyrin binds to one of these amines, electrical resistance of the carbon nanotube increases; this can be easily measured.

Liu said:

“We use these porphyrins to fabricate a very simple device where we apply a potential across the device and then monitor the current. When the device encounters amines, which are markers of decaying meat, the current of the device will become lower.”

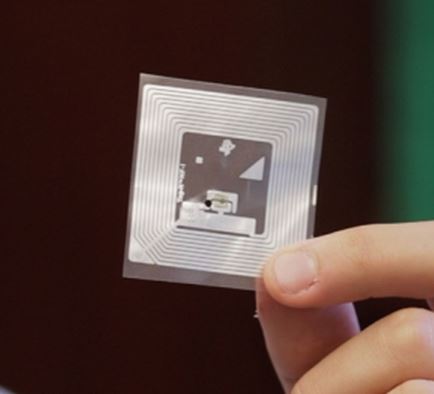

The sensor could be incorporated into a wireless platform. (Image: Melanie Gonick)

The scientists tested their new sensor on four types of meat: chicken, pork, salmon and cod. When refrigerated, they found that all four types remained fresh over four days. Left unrefrigerated, however, they all decayed at varying rates.

Other sensors can also detect signs of decaying meat, but they are not portable and tend to be significantly more expensive instruments that are not easy to operate.

Prof. Swager said:

“The advantage we have is these are the cheapest, smallest, easiest-to-manufacture sensors.”

The new sensor requires very little power, and could be incorporated into a wireless platform that Swager’s lab recently developed, so that a regular smartphone could read the output.

The scientists, who have filed a patent on the technology, hope to license it for commercial development.

The research was funded by the the Army Research Office and the National Science Foundation through MIT’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies.

Citation: “Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube/Metalloporphyrin Composites for the Chemiresistive Detection of Amines and Meat Spoilage,” Sophie F. Liu, Alexander R. Petty, Dr. Graham T. Sazama and Prof. Dr. Timothy M. Swager. Angewandte Chemie. Published 13 April, 2015. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201501434.