Mercury’s surface is dark and barely reflective because of a steady dusting of carbon from passing comets which covered the planet in a soot-like material over billions of years, a team of scientists believes.

Astronomers have long-wondered why Mercury’s surface is so dark. It is considerably darker than its closest neighbor with no atmosphere, our Moon.

Celestial bodies with no atmosphere are known to be darkened by impacts from tiny meteorites and solar wind bombardments, which create a thin coating of dark iron nanoparticles on their surface.

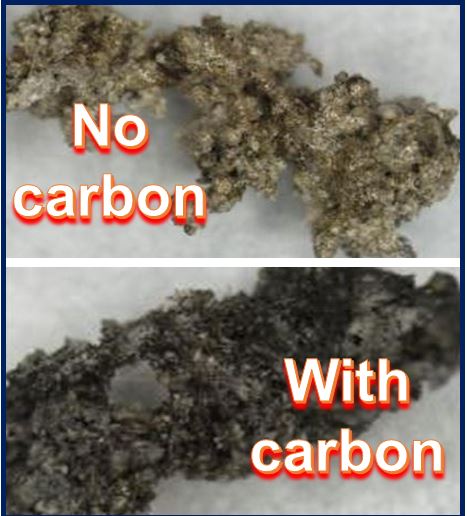

Impact material generated without the presence of carbon from complex organics (top) is lighter than material generated with carbon (bottom). (Image: Brown University)

However, spectral data (colour wavelength data) suggest Mercury’s surface contains very little nanophase iron – definitely not enough to explain why it is so dark.

Megan Bruck Syal, a postdoctoral researcher at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who was involved in the study while a graduate student at Brown University, said:

“It’s long been hypothesized that there’s a mystery darkening agent that’s contributing to Mercury’s low reflectance. One thing that hadn’t been considered was that Mercury gets dumped on by a lot of material derived from comets.”

Dr. Bruck Syal and colleagues wrote about their findings in the academic journal Nature Geoscience (citation below).

Billions of years of carbon-rich comet impacts

As comets approach Mercury’s neighbourhood near the sun, they frequently start to break up into very small pieces. Cometary dust is made up of up to 25% carbon by weight. Therefore, Mercury would be exposed to a steady dusting of carbon from these disintegrating comets.

Dr. Bruck Syal used a known estimate of micrometeorite flux at Mercury and a model of impact delivery, which allowed her to estimate how frequently cometary material would impact Mercury, how much carbon would settle on the planet’s surface, and how much would be thrown back into space.

According to her calculations, after billions of years of bombardment, the surface of Mercury consists of between 3% and 6% carbon.

The scientists then set out to determine how much darkening could be expected from all that impacting carbon.

They used the NASA Ames Vertical Gun Range, a 14-foot canon that simulates celestial impacts by firing projectiles at 16,000 mph (25,749 kph).

The scientists launched projectiles in the presence of sugar, a complex organic compound that behaves in the same way as comet material. The impact’s heat burns up the sugar, releasing carbon.

They fired the projectiles into material that mimics lunar basalt. Lunar basalt is the rock that makes up the dark patches on the nearside of the Moon.

Co-author Peter Schultz, professor emeritus of geological sciences at Brown University, said:

“We used the lunar basalt model because we wanted to start with something dark already and see if we could darken it further.”

Carbon is a stealth darkening agent

Their experiments showed that tiny carbon particles became deeply embedded in the material that had been melted by the impact. The process reduced the amount of light reflected by the target material to under 5%, which is about the same as Mercury’s darkest parts.

Schultz said:

“We show that carbon acts like a stealth darkening agent. From the standpoint of spectral analysis, it’s like an invisible paint.”

In Mercury’s case, that invisible paint has been accumulating for billions of years.

“We think this is a scenario that needs to be considered. It appears that Mercury may well be a painted planet,” Schultz said.

The study was funded by the Space Science Fellowship program and NASA’s Planetary Geology and Geophysics program.

Citation: “Darkening of Mercury’s surface by cometary carbon,” Megan Bruck Syal, Peter H. Schultz & Miriam A. Riner. Nature Geoscience. Publiched 30 March, 2015. DOI: 10.1038/ngeo2397.