Water at intermediate depths in the Pacific Ocean is warming up to a point where methane gas, trapped in frozen layers below the seafloor, is being released into water at an alarming rate.

According to a new study by researchers at the University of Washington, water at intermediate depth off the West Coast of the US is warming up to a point in which carbon deposits will begin to melt and release methane into the surrounding water.

Over the past forty years nearly 4 million tonnes of methane has been released from hydrate decomposition off Washington state – an amount each year equal to the amount of methane from natural gas that was released off the coast of Louisiana in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon blowout.

Researchers found that water off the coast of Washington is warming at a depth of 500 meters – where methane transforms from a solid to a gas.

This is worrying as methane is a greenhouse gas much more potent than carbon dioxide in warming the planet.

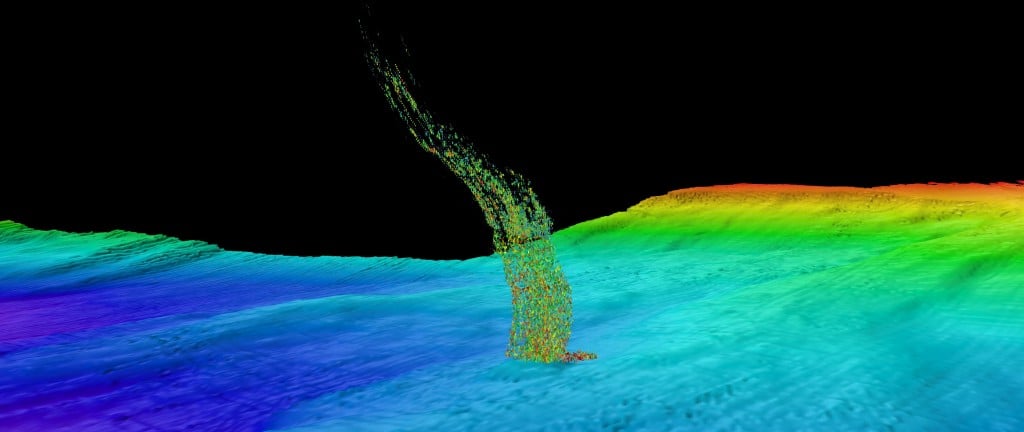

Sonar image of bubbles rising from the seafloor off the Washington coast. The base of the column is 1/3 of a mile (515 meters) deep and the top of the plume is at 1/10 of a mile (180 meters) deep. Photo Credit: Brendan Philip / UW

“A lot of the earlier studies focused on the surface because most of the data is there,” said co-author Susan Hautala, a UW associate professor of oceanography. “This depth turns out to be a sweet spot for detecting this trend.”

Evan Solomon, a UW assistant professor of oceanography and co-author of a paper to appear in Geophysical Research Letters, said:

“We calculate that methane equivalent in volume to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill is released every year off the Washington coast,”

“Methane hydrates are a very large and fragile reservoir of carbon that can be released if temperatures change,” Solomon said. “I was skeptical at first, but when we looked at the amounts, it’s significant.”

At cold temperatures methane combines with water and turns into a crystal called methane hydrate. The Pacific Northwest has very large deposits of methane hydrates because of its strong geologic activity. However, there are other coastlines around the world that could also be vulnerable to sea temperatures increasing.

“This is one of the first studies to look at the lower-latitude margin,” Solomon said. “We’re showing that intermediate-depth warming could be enhancing methane release.”

The reason why the water is warming is thought to come from the Sea of Okhotsk, where surface water becomes extremely dense and spreads east into the Pacific and then reaches the Washington coast.

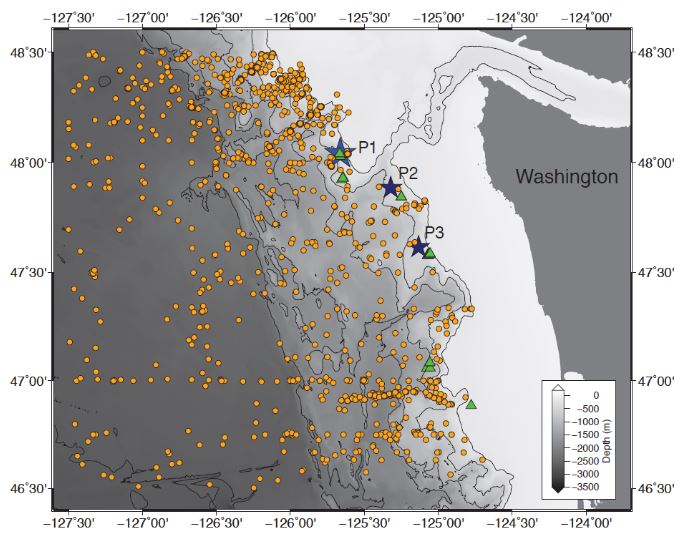

The yellow dots show all the ocean temperature measurements off the Washington coast from 1970 to 2013. The green triangles are places where scientists and fishermen have seen columns of bubbles. The stars are where the UW researchers took more measurements to check whether the plumes are due to warming water. Photo Credit: Una Miller / UW

As ocean temperatures rise the boundary between frozen and gaseous methane is going to move deeper and farther offshore. The Washington boundary has moved approximately 1km offshore since 1970 and the researchers estimate that the boundary for solid methane will move another 1 to 3 kms out to sea by 2100.

Researchers are now hoping to find a new way of to verify the calculations with new measurements. Over the past few years, fishermen have provided UW oceanographers with sonar images showing mysterious columns of bubbles.

“Those images the fishermen sent were 100 percent accurate,” Johnson said. “Without them we would have been shooting in the dark.”

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy.

References:

- “Warmer Pacific Ocean could release millions of tons of seafloor methane” Hannah Hickey – University of Washington

- “Dissociation of Cascadia margin gas hydrates in response to contemporary ocean warming” DOI: 10.1002/2014GL061606

Geophysical Research Letters – Susan L. Hautala, Evan A. Solomon, H. Paul Johnson, Robert N. Harris, and Una K. Miller