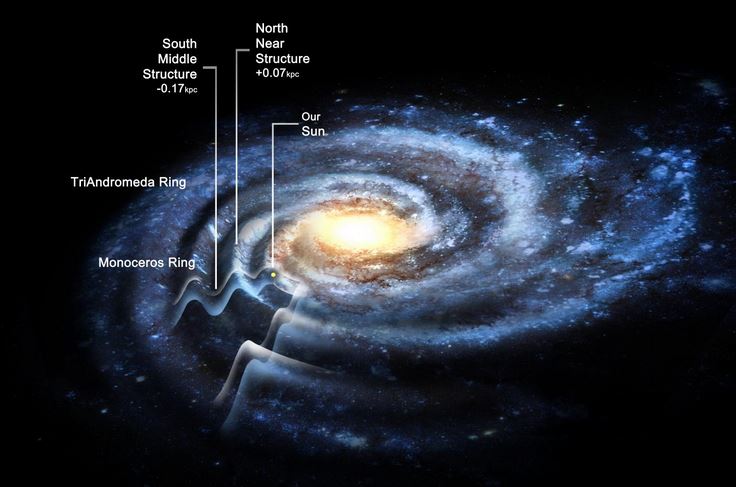

The Milky Way, our galaxy, is at least 50% bigger than most estimates, says a team of scientists who discovered that the galactic disk is contoured into many concentric ripples. Our Milky Way is corrugated.

The study, led by Professor Heidi Jo Newberg of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, re-examined Sloan Digital Sky Survey data which, in 2002, established that there was a bulging ring of stars beyond the known plane of the Milky Way.

Prof. Newberg, an American astrophysicist known for her work in understanding the structure of the Milky, said:

“In essence, what we found is that the disk of the Milky Way isn’t just a disk of stars in a flat plane–it’s corrugated. As it radiates outward from the sun, we see at least four ripples in the disk of the Milky Way.”

Our ‘rippled’ Milky Way may be 50% larger than previously estimated. (Image: Rensselaer)

“While we can only look at part of the galaxy with this data, we assume that this pattern is going to be found throughout the disk.”

Notably, their findings demonstrate that features previously observed as rings are in fact part of the galactic disk, extending the Milky Way’s known width from 100,000 to 150,000 light years across, said lead author Yan Xu, a scientist who works at the National Astronomical Observatories of China, part of the Chinese Academy of Science, Beijing. Mr. Xu is a former visiting scientist at Rensselaer.

Apparent ring is a ripple in the disk

Mr. Xu said:

“Going into the research, astronomers had observed that the number of Milky Way stars diminishes rapidly about 50,000 light years from the center of the galaxy, and then a ring of stars appears at about 60,000 light years from the center.”

“What we see now is that this apparent ring is actually a ripple in the disk. And it may well be that there are more ripples further out which we have not yet seen.”

The study, which was partly financed by the National Science Foundation, has been published in the academic journal Astrophysical Journal (citation below).

The density of light detected in the Milky Way reveals a rippling contour. (Image: Rensselaer)

Newberg, Xu and colleagues used data from the SDSS (Sloan Digital Sky Survey) to show an oscillating asymmetry in the main star count sequence on either side of the galactic plane, starting from the Sun and looking outward from the center of the galaxy.

In other words, when looking outward from the Sun, the mid-plane of the disk is perturbed down, then up, then down, and then up again.

National Science Foundation (NSF) program manager, Glen Langston, said:

“Extending our knowledge of our galaxy’s structure is fundamentally important. The NSF is proud to support their effort to map the shape of our galaxy beyond previously unknown limits.”

This new study builds on a 2002 finding in which the existence of the ‘Monoceros Ring’ was established by Prof. Newberg – an ‘over-density’ of stars at the outer edges of the galaxy that bulges above the galactic plane.

What is the ‘over-density’ of stars?

In 2002, Prof. Newberg saw evidence of another over-density of stars, between the Sun and the Monoceros Ring, but could not investigate further. With the additional data available from the SDSS, scientists recently returned to the mystery.

Prof. Newberg said:

“I wanted to figure out what that other over-density was. These stars had previously been considered disk stars, but the stars don’t match the density distribution you would expect for disk stars, so I thought ‘well, maybe this could be another ring, or a highly disrupted dwarf galaxy.”

When the team re-examined the data, they found four anomalies: one south of the galactic plane at 4-6 kilo-parsecs (kpc), one north of the plane at 2 kpc, a third to the north at 9-10 kpc, plus evidence of a fourth to the south at 12-16 kpc from the Sun.

A parsec is an astronomical unit of distance, equal to approximately 3.26 light years (3.086 × 1013 kilometers, 31 trillion kilometers or 19 trillion miles).

The Monoceros Ring is associated with the third ripple. The scientists also found that the oscillations appear to line up with the galaxy’s spiral arms’ locations.

Prof. Newberg said their findings support other recent studies, including a theoretical finding that a dark matter lump or dwarf galaxy passing through the Milky Way could produce a similar rippling effect. The ripples could, in fact, eventually be used to measure the lumpiness of dark matter in our galaxy.

Prof. Newberg said:

“It’s very similar to what would happen if you throw a pebble into still water – the waves will radiate out from the point of impact.”

“If a dwarf galaxy goes through the disk, it would gravitationally pull the disk up as it comes in, and pull the disk down as it goes through, and this will set up a wave pattern that propagates outward.”

“If you view this in the context of other research that’s emerged in the past two to three years, you start to see a picture is forming.”

Citation: “Rings and Radial Waves in the Disk of the Milky Way,” Yan Xu, Heidi Jo Newberg, Jeffrey L. Carlin, Chao Liu, Licai Deng, Jing Li, Ralph Schönrich, and Brian Yanny. The Astrophysical Journal. Published 11 March, 2015. DOI: 10.1088/0004-637X/801/2/105.

Video – The Corrugated Milky Way