Early global policy architects’ pessimism stunted developing economies during most of the twentieth century, a researcher from the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs wrote in a paper published in the new Journal of Policy and Complex Systems.

Major economists at the beginning of the 20th century, especially around 1911, emphasized that innovation and entrepreneurialism were vital components for economic growth and wealth, but added that they were not appropriate for developing nations. Their influential economic ideas stunted growth in several parts of the developing world for much of the century, Calestous Juma wrote.

Prof. Juma urges the developing markets and economic agencies to embrace the ideas turned down in the 1950s by “pessimistic” architects of early institutions and international development policies.

Juma’s paper examines the Impact of Joseph Schumpeter’s 1911 book – ‘The Theory of Economic Development’ – which put forward the notion that individual entrepreneurship and innovation are the dynamic foundations of a country’s economic development.

Schumpeter advanced the notion that ‘creative destruction’ and the renewal processes and tools within an economy constantly refresh the system, leading to increasing prosperity. Schumpeter, a Harvard scholar, was one of the most influential economists at the beginning of the 20th century.

Entrepreneurship & innovation rejected for 3rd world policies

His revolutionary ideas had a powerful influence on industrialized countries’ policymakers who implemented innovation-led policies. However, they were dismissed as inappropriate and irrelevant to developing nations in the 1950s within the IMF (International Monetary Fund), the World Bank and the UN (United Nations).

‘Pessimism’ prevailed in early development economics, Prof. Juma wrote, resulting in policymakers over-concentrating on “the use of basic or ‘appropriate technologies,’ central planning, role of bureaucracies as sources of economic stability, and food aid” for middle- and low-income nations, instead of entrepreneurship, industrial development and innovation.

After debating the issue for over ten years, Juma notes that the architects of development economics discarded innovation-inspiring policies for “static, linear, and incremental view of economic change” for the countries that had become newly independent.

Juma quotes Henry Wallich, a US central banker in the early 1950s and leading economic thinker who said “In applying this (Schumpeter’s) doctrine to the less developed countries of our day, we find that it does not fit.”

‘Derived development’ for poorer countries locked them in

Wallich said that in developing and under-developed nations, the entrepreneur “is not the main driving force, innovation is not the most characteristic process, and private enrichment is not the dominant goal.”

Wallich believed that developing nations derived innovation in other countries (“derived development”).

Prof. Juma said:

“This view would lock emerging countries at the tail end of the product cycle, making them perpetual importers of foreign products with no capacity for technological learning.”

“Technical fields such as science, technology, and engineering were largely considered irrelevant to emerging countries except in limited areas where they supported assimilation of imported products or inevitable areas of adaptive research such as plant breeding. Even more critical was the low priority given to higher education in general and higher technical education in particular.”

“For poor countries seeking to catch up economically, innovation-led growth provided a more intuitive path. The policies recommended for them, however, were tedious, hobbling and demoralizing.”

Some nations ignored ‘pessimism’ and thrived

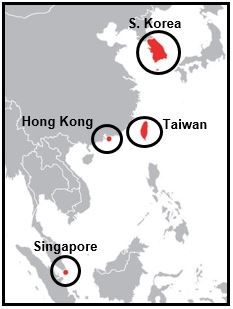

Some Asian developing countries ignored the pessimists and thrived, e.g. Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea (the four Asian Tigers). Today policymakers and researchers are reshaping development policies around innovation and entrepreneurship, Juma notes.

Prof Juma said “Schumpeter laid out the foundations for understanding how economies change over time. That was a century ago. Several enduring themes of his theory remain valid today and should be part of the core of the policies of emerging nations.”

According to Prof. Juma, developing countries and institutions today should:

- Prioritize the role of innovation in spreading prosperity, and not just for transforming economic systems to new levels of performance in all sectors.

- In order to lay the foundations for economic transformation, invest in transformative infrastructure projects.

- Enhance the technical capacity required to drive growth through the translation of skills into goods and services, especially in the fields of engineering.

- Entrepreneurs and risk-takers in the private and public sectors are crucial agents of innovation – their role should be emphasized.

When writing the paper, Prof. Juma gathered and analyzed data from a book which is tentatively titled – ‘How Economies Succeed: Innovation and the Wealth of Nations’. The book will be published in 2016.