After Scott Kelly and Mikhail Kornienko spent a whole year in space, their bodies will have experienced cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, neurobehavioral and other alterations. They will also have been exposed to various types of radiation. When an astronaut spends time in the weightless environment of space, there is a physical toll to pay.

If we are serious about sending humans on missions to Mars, we need to know how they would cope in deep space over prolonged periods.

What we learn from Kelly’s and Kornienko’s year in space will help determine how well we would fare on such missions, and what needs to be done to reduce the negative effects to a minimum.

After spending one whole year in space, Scott Kelly and Mikhail Kornienko will have lost some bone and muscle mass, and will probably have suffered some other physical problems. Back on Earth, they will eventually recover. (Image: nasa.gov)

After spending one whole year in space, Scott Kelly and Mikhail Kornienko will have lost some bone and muscle mass, and will probably have suffered some other physical problems. Back on Earth, they will eventually recover. (Image: nasa.gov)

Cardiovascular effects

Space exploration can be harmful for astronauts’ cardiovascular system. Those with pre-existing but undetected cardiovascular disease are at risk of life-threatening complications when they are far away from medical help.

Scientists at the National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NSBRI) are especially concerned about whether space radiation might affect endothelial cells – the ones that line our blood vessels – which might accelerate or initiate coronary heart disease.

The NSBRI Cardiovascular Alterations team, led by Dr. Benjamin D. Levine, says it is using new ultrasound techniques to assess changes in cardiac size, shape and function of astronauts over the course of their prolonged spaceflight on the International Space Station (ISS).

The human heart shrinks when we spend a long time in space, and its ability to fill completely is reduced. Researchers are currently trying to determine whether astronauts’ ability to maintain temperature control or exercise might be compromised.

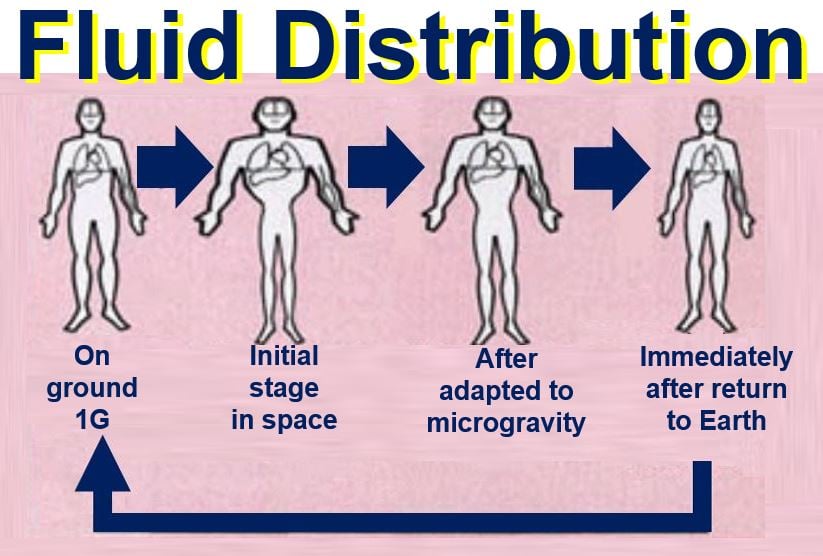

Within a few moments of being in space, fluid is immediately re-distributed to the upper body resulting in neck veins bulging out, a puffy face and sinus and nasal congestion. Gradually, the human body adapts to a certain extent. When the astronauts returns to Earth, fluid distribution goes back to normal. (Image: Wikipedia)

Within a few moments of being in space, fluid is immediately re-distributed to the upper body resulting in neck veins bulging out, a puffy face and sinus and nasal congestion. Gradually, the human body adapts to a certain extent. When the astronauts returns to Earth, fluid distribution goes back to normal. (Image: Wikipedia)

Bone and muscle loss

Astronauts in space lose muscle and bone from their lower back, legs and hips, because they don’t have to carry weight around like they do on Earth.

To put the bone loss in perspective, after the menopause, untreated women can lose from 1% to 1.5% of the bone mass from the hip in one year – this loss can occur in an astronaut in space in just one month!

The loss of bone and muscle mass can cause several problems for the crew during long-duration missions in space, including a higher risk of fall-related injuries and accidents (fractures), and a reduction in physical performance.

The NSBRI’s Musculoskeletal Alterations Team, led by Lori Ploutz-Snyder, is studying the mechanisms involved in muscle and bone loss, and whether being in a microgravity environment increases the risk of bone breaks and undermines fracture healing.

Dr. Ploutz-Snyder’s team is also researching bone loss induced by radiation exposure. They are also monitoring the benefits of physical exercise while in space to reduce bone and muscle loss, as well as investigating what nutritional and pharmaceutical interventions could complement exercise.

According to NASA: “The loss of bone mass that many people experience in space could eventually weaken the bone and so present problems when the person returns to a weight-bearing environment, such as the Earth or Mars.” (Image: nasa.gov. Credit: Johnson Space Center)

According to NASA: “The loss of bone mass that many people experience in space could eventually weaken the bone and so present problems when the person returns to a weight-bearing environment, such as the Earth or Mars.” (Image: nasa.gov. Credit: Johnson Space Center)

Neurobehavioural and psychosocial effect of being in space

Isolation and confinement has a greater effect on astronauts on long-duration space missions than terrestrial explorers or previous space travelers. A mission’s success depends greatly how each crew member deals with stress and the challenges of long space voyages.

The NSBRI’s Neurobehavioral and Psychosocial Factors Team, led by Dr. David F. Dinges, identifies neurobehavioral and psychological risks to crew health, and how productivity and safety might be affected.

The team’s objectives include developing methods to monitor behaviour and brain functions, and countermeasures to improve motivation, performance and quality of life.

ISS crew members have to do exercise in space, which reduces the bone and muscle loss effect of microgravity (not completely). (Image: nasa.gov)

ISS crew members have to do exercise in space, which reduces the bone and muscle loss effect of microgravity (not completely). (Image: nasa.gov)

Effects of radiation in space

Astronauts, especially those on exploration-class missions, are exposed to several types of radiation. Those who travel beyond LEO (low Earth orbit), are exposed to bursts of solar radiation, known as solar particle events, which could undermine their performance and result in mission failure.

Acute health problems related to radiation exposure include fatigue, skin injury, vomiting, nausea, and changes to white blood cell counts and the immune system.

Astronauts travelling beyond LEO are also exposed to galactic cosmic rays, which may lead to long-term effects including damage to the eyes, central nervous system and the cardiovascular system, as well as a greater risk of developing cancer.

The NSBRI’s Radiation Effects (RE) Team, led by Dr. Marjan Boerma, focusses on understanding the risks related to various types of space radiation and mitigating them.

Lots of data to analyse

Regarding Scott Kelly and Mikhail Kornienko, who both spent a whole year in space, NASA wrote:

“NASA astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko may have had a year-long stay in space, but the science of their mission will span more than three years.”

“One year before they left Earth, Kelly and Kornienko began participating in a suite of investigations aimed at better understanding how the human body responds to long-duration spaceflight.”

“Samples of their blood, urine, saliva, and more all make up the data set scientists will study. The same kinds of samples continued to be taken throughout their stay in space, and will continue for a year or more once they return.”

Astronauts’ health throughout a Mars mission

One of the main challenges NASA faces in its planned manned Mars mission, is ensuring humans are a ‘go’ for long-duration missions, and that astronauts will remain healthy and retain their full capabilities throughout the whole ordeal, including their return to Earth (and afterwards).

NASA scientists have plenty of data regarding how humans fare when living in microgravity for six months. However, we have known much less about what can happen for longer durations, that is, until now.

A Mars mission will probably last about three years, including the trip back. During about half that time, humans will be travelling to the Red Planet and back, while the other half will be spent on Mars.

NASA wrote:

“We need to understand how human systems like vision and bone health are affected by the 12 to 16 months living on a spacecraft in microgravity and what countermeasures can be taken to reduce or mitigate risks to crew members during the flight to and from Mars.”

“Understanding the challenges facing humans is just one of the ways research aboard the space station helps our journey to Mars.”

The results of Kelly’s and Kornienko’s test analyses will not be published until six months to six years after their return to Earth. The scientific process is a lengthy one, and processing the information from all the investigations tied to the one-year mission will be a major undertaking.

Not the first 1-year-in-space mission

Four humans had spent at least a year in orbit on a single mission aboard Russia’s Mir Space Station. They all took part in significant research proving that humans are able to live and work in space for one year or more.

However, this is the first time extensive studies have been performed using new techniques like genetic studies on long-duration crew members.

NASA says that data collected and analyzed on both Kelly and Kornienko will be shared between American and Russian scientists, as well as other international partners.

International collaboration is essential if we want to rapidly increase our biomedical knowledge regarding space travel.

Back to normal meals

After a whole year of eating food from cans and pouches and drinking through straws, Kornienko and Kelly will be able to eat their favourite ‘Earth foods’ again.

Their food intake – which is designed to provide the nutrients they need – has been closely monitored while aboard the ISS.

While crew members have some say in their on-orbit menus, they clearly cannot enjoy BBQs, messy spare ribs, and several other meals they ate back on Earth.

On returning to Earth and leaving the space capsule, astronauts are usually given a cucumber or a piece of fruit as they start their initial health checks. “After Kelly makes the long flight home to Houston, he will no doubt greatly savor those first meals,” NASA wrote.

Getting their strength back

The phrase ‘Use it or lose it’ is very apt, as far as returning astronauts are concerned. Crew members’ bones and muscles gradually wither away when they are in the weightless environment of space for a long time.

Even though they have a hearty exercise regime while in space to fight these effects, they still lose muscle and bone mass. Back on Earth they continue reconditioning and strength training.

Immediately after landing, they undergo Field Tests, and then Functional Task Tests when back at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, which assess how their body responds to living in microgravity for such a long time.

NASA wrote:

“Understanding how astronauts recover after long-duration spaceflight is a critical piece in planning for missions to deep space.”

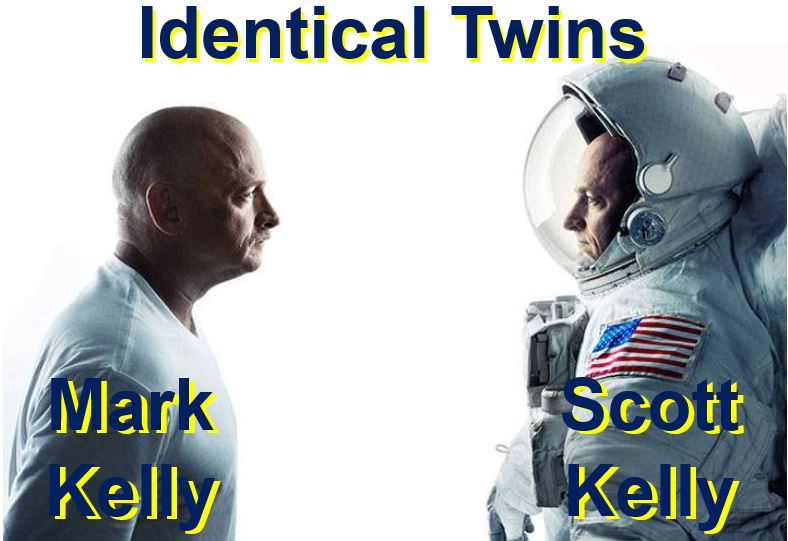

Scott Kelly has an identical twin brother – Mark. This is extremely useful for researchers who can use Earth-based Mark as the human control in their studies. (Image: nasa.gov)

Scott Kelly has an identical twin brother – Mark. This is extremely useful for researchers who can use Earth-based Mark as the human control in their studies. (Image: nasa.gov)

Kelly has an identical twin brother

Scott Kelly has an identical twin brother, who used to be an astronaut. This is extremely useful for scientists, because they can use Mark (the twin brother) as a human control on the ground during Scott’s year-long stay in microgravity.

Regarding the twin brothers, NASA wrote:

“The Twins Study is comprised of 10 different investigations coordinating together and sharing all data and analysis as one large, integrated research team.”

“The investigations focus on human physiology, behavioral health, microbiology/microbiome and molecular/omics. The Twins Study is multi-faceted national cooperation between investigations at universities, corporations, and government laboratories.”

The completion of these two men’s one year missions and the related studies will help guide the next steps when planning deep-space, long-duration voyages that will be required as humans move farther into our Solar System.

Video – How space flight affects human body

The effects of space flight add up over time. This video explains how the human body is affected.