Included among the 50 exciting discoveries about Pluto, are its possible ice volcanoes and moons that orbit the planet like spinning tops, researchers on the New Horizons team from NASA’s Ames Research Center at Mountain View, California, announced at the 47th Annual Meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences in National Harbor, Maryland.

New Horizons is an interplanetary space probe that was launched on 19th January, 2006, as part of NASA’s New Frontiers program. On 14th July, 2015, it flew very close (12,500 kilometers – 7,800 miles) to Pluto’s surface, making it the first spacecraft ever to explore the dwarf planet.

Jim Green, director of planetary science at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said:

“The New Horizons mission has taken what we thought we knew about Pluto and turned it upside down. It’s why we explore – to satisfy our innate curiosity and answer deeper questions about how we got here and what lies beyond the next horizon.”

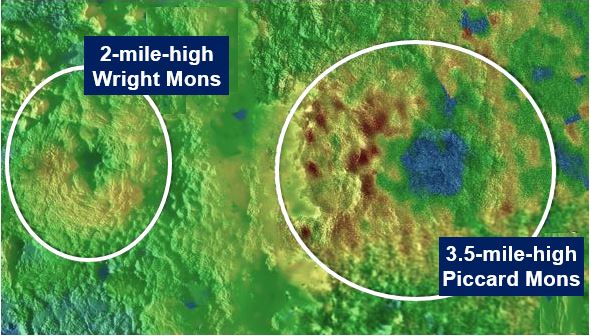

Scientists have discovered that two mountains on Pluto’s surface, informally named Piccard Mons and Wright Mons, could be ice volcanoes. (Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

Scientists have discovered that two mountains on Pluto’s surface, informally named Piccard Mons and Wright Mons, could be ice volcanoes. (Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

Possibly two ice volcanoes on Pluto’s surface

New Horizons geologists combined pictures of Pluto’s surface to create 3-D maps that suggest that the dwarf planet’s most distinctive mountains may be cryovolcanoes, i.e. ice volcanoes that could have been active in the recent geological past.

Mission Principal Investigator, Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said:

“It’s hard to imagine how rapidly our view of Pluto and its moons are evolving as new data stream in each week. As the discoveries pour in from those data, Pluto is becoming a star of the solar system.”

“Moreover, I’d wager that for most planetary scientists, any one or two of our latest major findings on one world would be considered astounding. To have them all is simply incredible.”

The two ice-volcano candidates are enormous features, measuring tens of miles across and several miles high.

Oliver White, New Horizons postdoctoral researcher at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, said:

“These are big mountains with a large hole in their summit, and on Earth that generally means one thing – a volcano. If they are volcanic, then the summit depression would likely have formed via collapse as material is erupted from underneath.”

“The strange hummocky texture of the mountain flanks may represent volcanic flows of some sort that have traveled down from the summit region and onto the plains beyond, but why they are hummocky, and what they are made of, we don’t yet know.”

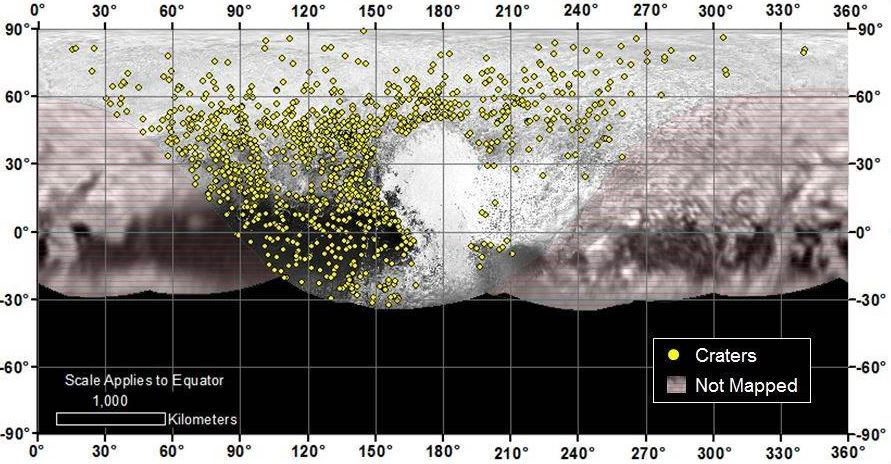

The locations of over 1,000 craters mapped on Pluto’s surface indicate a wide range of ages, which likely means the dwarf planet has been geologically active for billions of years. (Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

The locations of over 1,000 craters mapped on Pluto’s surface indicate a wide range of ages, which likely means the dwarf planet has been geologically active for billions of years. (Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

Even though they look like the volcanoes that spew the molten rock we are used to here on Earth, the cryovolcanoes on Pluto are likely to emit a melted slurry of substances including ammonia or methane, nitrogen, and water ice.

If the presence of volcanoes on Pluto is confirmed, scientists will have a vital clue to its atmospheric and geologic evolution.

Jeffrey Moore, New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging team leader, at Ames, said “After all, nothing like this has been seen in the deep outer solar system.”

Pluto has a long history of geologic activity

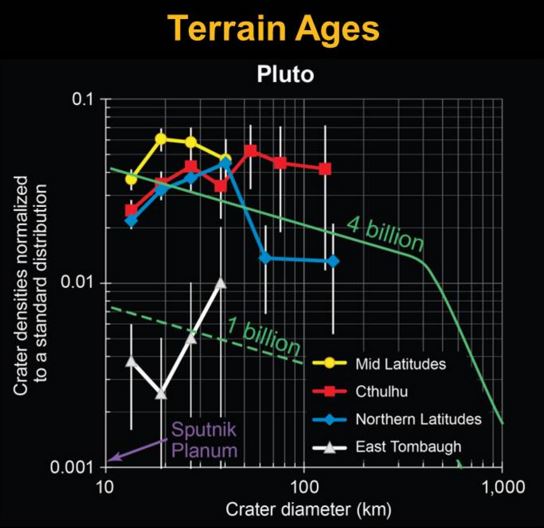

The surface of Pluto ranges in age – from relatively young, to intermediate, to ancient – according to new data gathered from New Horizons.

According to New Horizons data, at least two (perhaps all four) of Pluto’s small moons may have merged with smaller moons. (Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

According to New Horizons data, at least two (perhaps all four) of Pluto’s small moons may have merged with smaller moons. (Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

Space scientists count the number of crater impacts to determine how old a surface area of a planet is. Older regions tend to have a higher density of crater impacts.

According to crater counts of Pluto’s surface areas, some regions date back to just after the planets of our solar system were formed, approximately four billion years ago.

However, vast areas of the dwarf planet’s surface were ‘born yesterday’, geologically speaking. They were probably formed within the last 10 million years. This region, called Sputnik Planum, appears on the left side of Pluto’s ‘heart’ – according to images received so far, it has no craters at all.

New crater-count data also reveal the presence of ‘middle-aged’ (intermediate) terrains on Pluto’s surface, suggesting that Sputnik Planum is not an anomaly. In other words, throughout most of its 4-billion-year history, Pluto has probably been geologically active.

Kelsi Singer, a postdoctoral researcher who works at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, said:

“We’ve mapped more than a thousand craters on Pluto, which vary greatly in size and appearance. Among other things, I expect cratering studies like these to give us important new insights into how this part of the solar system formed.”

According to New Horizons data, Pluto’s surface ranges in age from ancient to extremely young. (Image: Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

According to New Horizons data, Pluto’s surface ranges in age from ancient to extremely young. (Image: Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

The Solar System’s building blocks

The New Horizons team says the crater counts are giving them a new insight into the structure of the Kuiper Belt itself. Pluto is in the Kuiper Belt – a region of the Solar System beyond the planets, extending from Neptune’s orbit (at 30 AU) to about 50 AU from the Sun (1 AU = the average distance from the Earth to the Sun).

Pluto and its large moon Charon have relatively few smaller craters. This suggests that the Kuiper Belt, the least-explored region of our solar system, probably had fewer smaller objects than scientists believe. A ‘smaller object’, in this text, is half-a-mile across or less.

New Horizons scientists now doubt whether Kuiper Belt objects formed by accumulating much smaller objects (a longstanding model). The dearth of small craters on Charon and Pluto support other models that theorize that larger Kuiper Belt objects may have formed directly, i.e. they were about the same size when formed as they are now.

In fact, this new evidence suggesting that most Kuiper Belt objects were ‘born large’ has researchers excited that New Horizons’ next potential target – the 40 to 50 kilometer wide KBO (Kuiper Belt Object) called 2014 MU69 – may offer the first detailed observation of such a pristine, original building block of our solar system.

New Horizons – the interplanetary spacecraft launched as part of NASA’s New Frontiers program. (Image: Wikipedia)

New Horizons – the interplanetary spacecraft launched as part of NASA’s New Frontiers program. (Image: Wikipedia)

Pluto has spinning, merged moons

The New Horizons team is also learning a great deal about Pluto’s amazing system of moons, and their fascinating properties.

Virtually every other moon in our solar system, including Earth’s moon, has one side facing toward the planet all the time – it is in synchronous rotation. Pluto’s small moons are different.

Pluto’s small moons rotate rapidly. Hydra, for example, its most distant moon, rotates 89 times during a single lap around the dwarf planet.

The researchers think these spin rates are not constant, because Charon exerts a powerful torque that prevents the small moons from settling down into synchronous rotation.

The scientists were also surprised at how much Puto’s moons wobble.

Co-investigator Mark Showalter, who works at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California, said “Pluto’s moons behave like spinning tops.”

Images of Pluto’s four smallest moons suggest some of them could have merged with other moons in the past.

Showalter said:

“We suspect from this that Pluto had more moons in the past, in the aftermath of the big impact that also created Charon.”

NASA Video – Pluto’s spinning moons

This NASA animation shows Pluto’s small moons behaving like spinning tops as they orbit the dwarf planet.