Harbour porpoises are master hunters, they catch about ninety percent of all the prey they pursue, says a team of scientists from Scotland, Germany and Denmark. They live on an ultra-energetic knife-edge of constant eating and hunting in order to survive.

Danuta Wisniewska, a postdoctoral researcher at Aarhus University in Denmark, and colleagues explained in the journal Current Biology (citation below) that the porpoise’s constant need to catch prey makes it vulnerable to increased human activities in the seas.

The scientists used tiny computer tags attached with suction caps to monitor the movements and echolocation sound that porpoises make as they hunt, as well as the echoes bouncing back from prey.

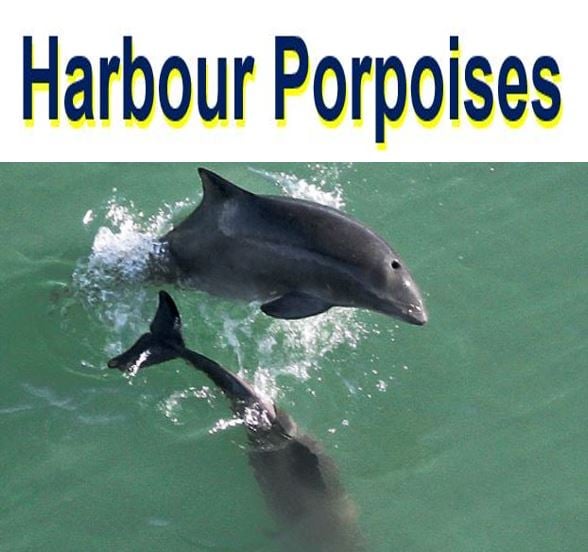

‘Hit-and-run mating’. According to the US National Wildlife Federation: The male porpoise rushes at females several times until they connect. He then tries to push as much sperm into her as he can. When it is over, the male often leaps fully out of the water, as in the image above. (Image: nwf.org)

‘Hit-and-run mating’. According to the US National Wildlife Federation: The male porpoise rushes at females several times until they connect. He then tries to push as much sperm into her as he can. When it is over, the male often leaps fully out of the water, as in the image above. (Image: nwf.org)

Porpoises hunt day and night

By analysing the echoes, the researchers could measure how often porpoises tried to catch fish, as well as the size of their prey, and whether it got away.

The data showed that porpoises hunt fish under 5cm long – they do this continuously day and night. The average porpoise catches up to 3,000 fishes per day.

With such an amazing success rate – 90% – porpoises are right up there among the most successful hunters on Earth.

Experts have long wondered how these relatively small echolocating predators can eat enough to survive in their cold environment. The average porpoise weighs 50kg (110lbs) and is about 1.5 metres (4.92 feet) long.

Mother and calf. The gestation of the mother is typically 10-to-11 months. The majority of births occur in late spring or summer. Calves are weaned at 8-to-12 months. (Image: porpoise.org)

Mother and calf. The gestation of the mother is typically 10-to-11 months. The majority of births occur in late spring or summer. Calves are weaned at 8-to-12 months. (Image: porpoise.org)

The researchers were surprised at how continuously porpoises eat. Previous tagging studies had suggested that they ate infrequently, but this made no sense given the number of small fish found in the stomachs of stranded porpoises.

Lead author, Dr. Wisniewska, said:

“Studying how animals hunt in the wild is important in ecology but is also really challenging – it is difficult to capture what both predator and prey are doing at the same time. This is the first time we have been able to measure simultaneously how a marine mammal hunts and how often it is successful.”

Porpoises use sound echoes to locate prey

Co-author, Dr. Mark Johnson, SMRU Senior Research Fellow at the St. Andrews’ School of Biology, who developed the tags that were used in this study, said:

“The trick here was to tap into the echolocation sounds that porpoises use to sense their environment. Porpoises make hundreds of clicks a second as they approach prey and the echoes coming back give us incredible detail about what the prey are doing.”

Harbour porpoises share the seas around northern Europe with dense ship traffic, fisheries, oil industry infrastructure, and a growing array of tide and wind turbines.

Although the small fish that porpoises target are of no interest to commercial fisheries, porpoises are often by-caught in fishing gear, a problem that has become a major threat to some populations.

According to recent studies, porpoises may be affected from boat noise, oil exploration and underwater construction.

Senior author, Peter Madsen, a professor of zoophysiology at Aarhus University in Denmark, said:

“Relying on such small prey makes porpoises especially vulnerable to disturbance. They are like shrews that can’t stop hunting for long without it having dire consequences.”

The study was supported by the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation – the aim was to understand how increasing development in the northern European seas may be affecting porpoises and their populations.

In a Summary which describes the main article in the journal, the authors wrote:

“Porpoises therefore target fish that are smaller than those of commercial interest, but must forage almost continually to meet their metabolic demands with such small prey, leaving little margin for compensation.”

“Thus, for these “aquatic shrews,” even a moderate level of anthropogenic disturbance in the busy shallow waters they share with humans may have severe fitness consequences at individual and population levels.”

Citation: “Ultra-High Foraging Rates of Harbor Porpoises Make Them Vulnerable to Anthropogenic Disturbance,” Jeanne Shearer, Signe Sveegaard, Lee A. Miller, Danuta Maria Wisniewska, Mark Johnson, Jonas Teilmann, Laia Rojano-Doñate, Ursula Siebert and Peter Teglberg Madsen. Current Biology, Vol. 26 Iss. 10, May 23, 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.069.

Video – Harbour Porpoises

Harbour porpoises are common in the colder coastal water of the North Pacific, North Atlantic and the Black Sea.