Butchery tools used as early as 1.8 million years ago drove early human communication and teaching, an international team of researchers has found.

Scientists from the University of St Andrews in Scotland, the University of Liverpool in England, and the University of California, Berkeley, believe that early Stone Age slaughtering tools were the seeds of human communication.

Their study has been published in the journal Nature Communications.

The team, who brought together expertise in evolutionary biology, archeology, and psychology, say their findings shed new light on the power of human culture to shape evolution.

They say their study is the largest so far to examine gene-culture co-evolution in the context of prehistoric Oldowan tools. Oldowan relates to the early Lower Paleolithic culture of Africa, dated about 1.5 – 2 million years ago. Ancient human’s oldest cutting devices are believed to come from this period.

The study authors believe that communication among our earliest ancestors may have been much more sophisticated than previously thought. There is evidence pointing to teaching, and even maybe a primitive proto-language existing as early as 1.8 million years ago.

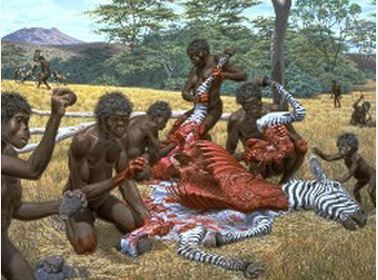

Stone tools used 2.5 million years ago by our oldest hominin ancestors probably triggered the evolution of human communication. (Illustration by Jay Matternes)

Lead author, Dr Thomas Morgan, who is currently a psychology researcher at UC Berkeley, said:

“Our findings suggest that stone tools weren’t just a product of human evolution, but actually drove it as well, creating the evolutionary advantage necessary for the development of modern human communication and teaching.”

“Our data show this process was ongoing two and a half million years ago, which allows us to consider a very drawn-out and gradual evolution of the modern human capacity for language and suggests simple ‘proto-languages’ might be older than we previously thought.”

Dr. Morgan and Natalie Uomini, from the University of Liverpool, reached their conclusion by carrying out a series of experiments in teaching modern humans the art of “Oldowan stone-knapping” – where butchering “flakes” are created by hammering a hard rock against some types of volcanic or glassy rocks, such as flint or basalt.

Dr. Thomas Morgan is the lead researcher on the study. (Photo: UC Berkeley)

The practice of stone-knapping dates back to the Lower Paleolithic period in eastern Africa, and persisted unchanged for about 700,000 years until the more advanced Acheulean hand-axes and cleavers appeared.

Our earliest ancestors, such as Homo habilis and even older Australopithecus garhi practiced stone-knapping.

In the experiment, 180 college students were taught Oldowan stone-knapping skills. The scientists found that spoken communication was much more effective than imitation or non-verbal presentations or gestures at achieving the best quality and highest volume of flakes in the shortest time possible, and with the least waste.

The volunteers were divided into 5- or 10-member “learning chains”, the aim being to measure the rate of transmission of ancient butchery technology, and to determine whether the use of language might get the best results.

The head of the chain would see a knapping demonstration, and would be given the raw materials plus five minutes to have a go. Then, he or she would show the next individual in the chain, who in turn showed it to the next participant, etc.

Individual competence was considerably improved when instructions were given verbally, compared to teaching without speech.

Dr. Morgan said:

“If someone is trying to learn a skill that has lots of subtlety to it, it helps to engage with a teacher and have them correct you. You learn so much faster when someone is telling you what to do.”

As far as Oldowan hominins are concerned, Dr. Morgan added “They were probably not talking. These tools are the only tools they made for 700,000 years. So if people had language, they would have learned faster and developed newer technologies more rapidly.”

With no language, the scientists say that a hominin genius – for example, an Oldowan Steve Jobs – would have found it extremely difficult to pass on his/her visionary ideas.

However, the demand for Oldowan tools probably planted the seeds of language, teaching and learning. It drove hominins to communicate better, and eventually allowed the advent of Acheulean hand-axes and cleavers approximately 1.7 million years ago.

Morgan explained:

“To sustain Acheulean technology, there must have been some kind of teaching, and maybe even a kind of language, going on, even just a simple proto-language using sounds or gestures for ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ or ‘here’ or ‘there’.”

Indeed, according to available evidence, when the Oldowan stone-tool industry began it was probably not being taught. Communication methods to teach it were likely developed later.

Dr. Morgan continued:

“At some point they reached a threshold level of communication that allowed Acheulean hand axes to start being taught and spread around successfully and that almost certainly involved some sort of teaching and proto-type language.”

Citation: “Experimental evidence for the co-evolution of hominin tool-making teaching and language,” T. J. H. Morgan, N. T. Uomini, L. E. Rendell, L. Chouinard-Thuly, S. E. Street, H. M. Lewis, C. P. Cross, C. Evans, R. Kearney, I. de la Torre, A. Whiten & K. N. Laland. Nature Communications. Article number: 6029. doi:10.1038/ncomms7029.

Video – Making butchering tools, Stone Age style

In this US Berkeley video, Dr. Morgan demonstrates stone-knapping, how our hominin ancestors made sharp tools out of rocks in the Stone Age.