The singing fish mystery has finally been solved – the night humming is triggered by a hormone that tells most animals, including humans, when it is time to go to sleep – melatonin. For humans and most other living creatures, melatonin anticipates the daily onset of darkness. Not for the singing fish, in his case – it affects the males only – it tells him to start his courtship humming.

For much of the animal kingdom, melatonin, which regulates our body clock, is involved in the synchronization of the circadian rhythms of physiological functions including blood pressure regulation, sleep timing, seasonal reproduction, and several others.

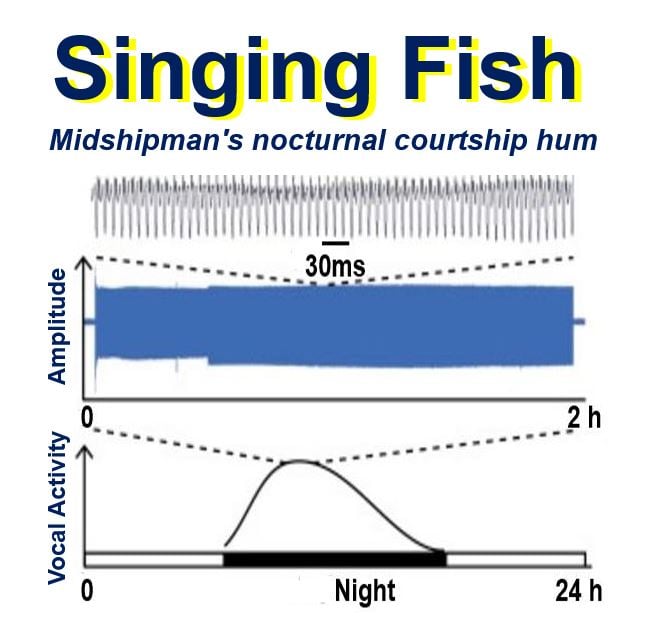

The courtship singing of male midshipman fish, known as ‘hums’, are uttered almost exclusively at night during the summer breeding season. Non-stop hums can last from minutes to over an hour, shown by the 1.85 hr courtship hum recorded from a captive male (blue trace), and are produced repetitively throughout a night of activity. (Image: cell.com)

The courtship singing of male midshipman fish, known as ‘hums’, are uttered almost exclusively at night during the summer breeding season. Non-stop hums can last from minutes to over an hour, shown by the 1.85 hr courtship hum recorded from a captive male (blue trace), and are produced repetitively throughout a night of activity. (Image: cell.com)

Melatonin makes the singing fish sing

However, for the singing fish – specifically the male Plainfin Midshipman Fish (Porichthys notatus) – melatonin tells him it is time for his night-time vocalizations; the aim being to attract mates.

About thirty years ago, houseboat dwellers in San Francisco Bay were puzzled by a humming sound that started abruptly in the late evening and would suddenly stop in the morning.

Rumours were rife among the local human population – perhaps the droning hum came from some sinister underwater military exercise, the shifting of the tectonic plates under the sea, or maybe even some enigmatic alien that was communicating with others of its kind.

After a lengthy investigation, the culprit was found: the male plainfin midshipman fish, a nocturnal creature that buries itself in the sand or mud in the intertidal zone during the day. At night, this fish floats just above the seabed.

(Porichthys notatus), which can grow to 15 inches (38 cm) in length, lives along the Pacific coast from Baja California to Alaska.

Andrew Bass, professor of neurobiology and behavior in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and Dr. Ny Y. Feng, a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, wrote about their latest study and findings in the academic journal Current Biology (citation below).

Melanin has opposite effect on the singing fish

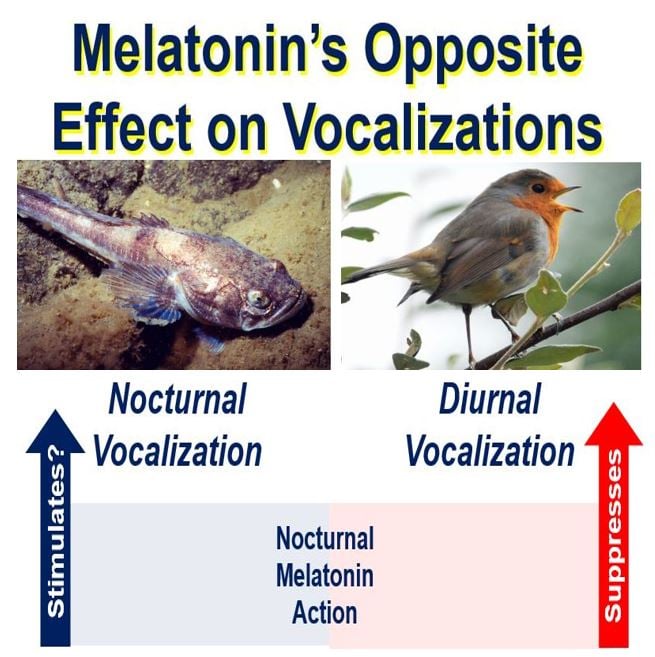

The authors explain how melatonin, rather than sending this nocturnal fish to sleep, tells him it is time to start his courtship hums.

Scientists know much more about the roles of melatonin and circadian rhythms in diurnal than nocturnal vertebrates. Our knowledge about the role of melatonin in fishes that vocalize during the mating season is very limited.

Other studies on day-active (diurnal) songbirds show that melatonin stops them singing at night, but increases syllable-length when these birds do sing.

A nest with male and female plainfin midshipman fish (Porichthys notatus). Attached to the rock you can see developing embryos. (Image: news.cornell.edu. Credit: Margaret A. Marchaterre)

A nest with male and female plainfin midshipman fish (Porichthys notatus). Attached to the rock you can see developing embryos. (Image: news.cornell.edu. Credit: Margaret A. Marchaterre)

In this latest study, Dr. Feng and Prof. Bass found that melatonin has an opposite effect on the male plainfin midshipman fish compared to day-active birds – the release of this hormone provides a ‘go signal’ for night singing.

Interestingly, when the hormone is released the calls lengthen when the fish sings, as they do with diurnal songbirds.

Prof. Bass, the senior author, said:

“Our results, together with those of others that also show melatonin’s actions on vastly different timescales, highlight the ability of hormones in general to regulate the output of neural networks in the brain to control distinct components of behavior.

“In the case of melatonin, one hormone can exert similar or different effects in diurnal vs. nocturnal species depending on the timescale of action, from day-night rhythms to the duration of single calls.”

Dr. Feng, who completed his Ph.D. at Cornell this year, said:

“Melatonin is an ancient and multifunctional molecule that is found almost ubiquitously in the animal kingdom.”

“Similarly, circadian rhythms govern the daily lives of diverse lineages, from plants to animals. Our study helps cement melatonin as a timing signal for social communication behaviors.”

Wild midshipman fish taken to the lab

Prof. Bass and Dr. Feng brought wild-caught midshipman fish into the laboratory, where they were able to control lighting. In one experiment, they tested whether the fish’s daily nocturnal song was controlled by an internally-generated circadian rhythm.

The fishes were placed in constant darkness, without any light cues at all, for seven consecutive days. The researchers found that they still sang, but on a 25-hour schedule so they began their singing one hour later each night.

Dr. Feng explained:

“You can think of it as a clock that can help the fish predict the best time to be vocally active. We found that this clock ran with a delay of about an hour, causing a drift in vocal activity with respect to the 24 hour light-dark cycle, highlighting the importance of internal clocks to be recalibrated by environmental cues on a daily basis.”

To understand what melatonin’s effect on the fishes was, they were exposed to constant light for 10 successive days. The pineal gland produces melatonin in vertebrates when it is dark, and constant light suppresses the fish’s humming significantly. However, when they were given a melatonin substitute, the fishes continued to hum, though without any rhythm and at random times of day.

Dr. Feng said:

“Melatonin acts as a ‘go signal’ for the nocturnal call of the midshipman fish. Surprisingly, at the single call timescale, constant light also decreased hum duration, but melatonin maintained hum duration at normal levels, a finding also found in diurnal birds.”

The researchers located specific melatonin receptors – sites where melatonin triggers an action within the brain – in brain regions that control social and reproductive behaviours, including vocal initiation centres, the same as in other vertebrates.

The study was funded by Cornell Neurobiology & Behavior Animal Behavior Grants, Sigma Xi Research Grants, and the National Science Foundation.

Citation: “‘Singing Fish’ Rely on Circadian Rhythm and Melatonin for the Timing of Nocturnal Courtship Vocalization,” Ni Y. Feng & Andrew H. Bass. Current Biology. September 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.079.

Video – Melatonin and singing fish

In this Cell Press video, Prof. Bass explains how melatonin affects the nocturnal Plainfin Midshipman Fish. Rather than telling the fish that it is time to sleep, melatonin stimulates night-time courtship humming.