Treachery, moral disputes and feelings of betrayal triggered a significant increase in the rate at which humans spread across the globe about 100,000 years ago, says a scientist from the University of York in the United Kingdom.

It was not until 100,000 years ago that we started developing a dark side. A trait which encouraged a growing number of people to ‘leave town’ because former friends or allies had felt let down and did not want them around any more.

Dr. Penny Spikins, Senior Lecturer in the Archaeology of Human Origins at the University’s Department of Archaeology, says that betrayal of trust was the ‘missing link’ that explains why the spread of humans geographically suddenly accelerated so rapidly.

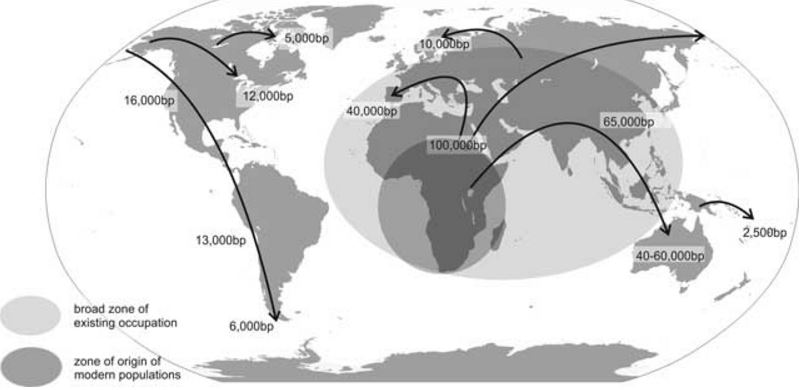

Human dispersal pattern after 100,000 BP. (Image: openquaternary.com)

Human dispersal pattern after 100,000 BP. (Image: openquaternary.com)

Prior to 100,000 years ago, humans were slow and principally governed by environmental events caused by ecological changes or population increases. Suddenly, human populations began to spread remarkably fast and across several major environmental barriers.

Dr. Spikins insists that these changes are associated with changes in human emotional relationships.

In the academic journal Open Quaternary, Dr. Spikins explains that neither population increases nor ecological changes can adequately explain why humans migrated to new regions, starting approximately 100,000 years ago.

Humans developed a dark side

As time passed, the author believes that as commitments to fellow neighbours became more crucial to survival, and human communities became increasingly driven to find and punish those who were deceitful, cheated or betrayed trust, the ‘dark side’ of human nature also developed and evolved.

Moral disputes driven by a sense of being let down – betrayal and broken trust – gradually became more common, and encouraged our ancient ancestors to put distance between them and those they considered to be their rivals.

The emotional bonds which helped hold populations together during difficult times had a darker side in profound reactions to perceived treachery and betrayal – traits which modern humans still possess.

Other animals do not have this dark side

As social networks became more extensive, there were greater opportunities to find distant allies with whom to set up new colonies, while more efficient and deadly hunting technology meant that any person holding a grudge was in danger.

It was human emotions, however, that provided the force of repulsion from existing occupied areas – a feature not observed in other animals.

Early hominins were limited in distribution to specific environments, mainly grasslands and open woodland.

Homo erectus’s expansion out of Africa into Asia 1.6 million years ago was motivated by the need to find more large scale grasslands, according to scientists.

Neanderthals, on the other hand, lived in the arid and cold parts of Europe. All ancient species adapted extremely slowly to new opportunities for settlement and were nearly always put off by environmental and climatic barriers.

100,000 years ago, humans started spreading more rapidly

Dr. Spikins points out that modern human populations were not put off by biogeographical barriers when looking for new places to live. They moved into the colder regions of Northern Europe, crossed deserts and jungles, tundra, and major deltas such as the Indus and Ganges. Even the much longer distances to Australia and Pacific Islands were tackled successfully.

Betrayals of trust arising from moral disputes contributed significantly towards people’s decisions to tackle risky and apparently inhospitable environments, the aim being to avoid physical harm at the hands of revengeful or disgruntled former allies or friends.

Offenders and perhaps also their allies within a social network would have felt driven to ‘get out of town’.

Dr. Spikins commented:

“Active colonisations of and through hazardous terrain are difficult to explain through immediate pragmatic choices. But they become easier to explain through the rise of the strong motivations to harm others even at one’s own expense which widespread emotional commitments bring.”

“Moral conflicts provoke substantial mobility — the furious ex ally, mate or whole group, with a poisoned spear or projectile intent on seeking revenge or justice, are a strong motivation to get away, and to take almost any risk to do so.”

“While we view the global dispersal of our species as a symbol of our success, part of the motivations for such movements reflect a darker, though no less ‘collaborative’, side to human nature.”

Reference: “The Geography of Trust and Betrayal: Moral disputes and Late Pleistocene dispersal,” Penny Spikin. Open Quaternary. November 25, 2015. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/oq.ai.