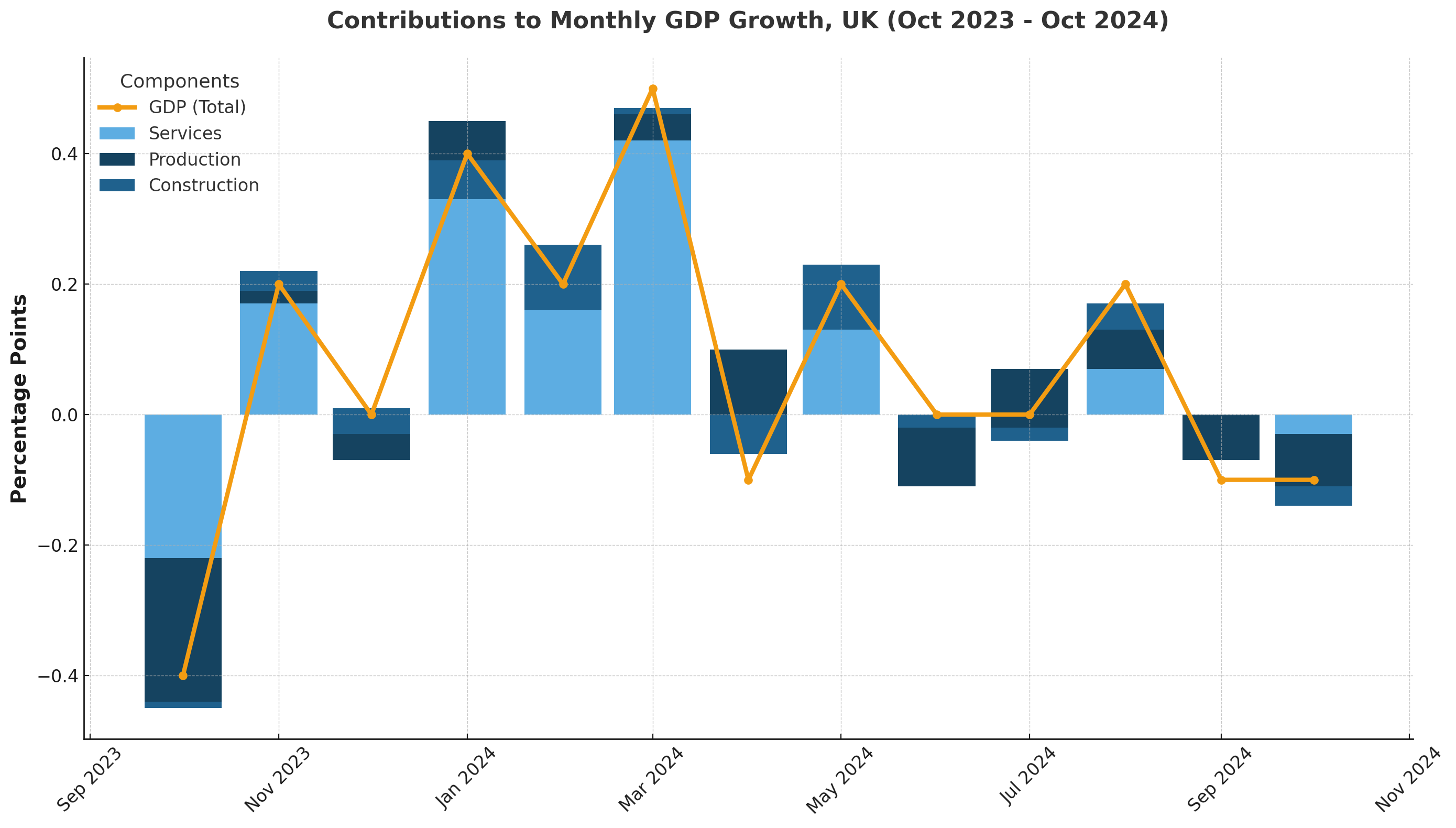

Britain’s economy slipped again in October, dropping 0.1%, and people are growing restless. This marks the second straight month of decline. Economists had expected a small boost in GDP, so this new data feels like a letdown. The UK’s numbers have seesawed all year, but right now, it looks like the needle isn’t moving in a good direction.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves acknowledges the drop is “disappointing.” She insists the government has laid the groundwork for eventual growth, but people are tired of waiting. The government’s first budget, introduced in October, included tax hikes and other tough pills to swallow. While officials say these moves will stabilize things later, many businesses say they’re feeling the pain now. Some delayed spending until they knew what was coming in the budget, while others scrambled to finish deals before new taxes kicked in. It’s a messy scene, and no one seems entirely sure what the long-term outcome will be.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s pledge to make Britain the fastest-growing major economy now feels like a heavy lift. The economy has barely grown over the last few months. Granted, some data is still early and may be revised, but the pattern isn’t comforting. Manufacturers took a hit, construction slowed down, and services—a huge slice of the economy—flatlined. Even pubs and restaurants, which many hoped would lead a rebound, reported weak months.

There are still tiny glimmers of hope. A recent consumer survey suggests households feel slightly better about their finances next year, although they remain pretty unsure about the broader economic landscape. Global factors haven’t helped. Britain’s trading partners aren’t exactly roaring ahead, and the lingering effects of recent crises still cast a long shadow.

Critics, including the Conservative opposition, say the government’s rhetoric and decisions have damaged confidence. They argue that continually warning of tough times and imposing heavy levies on businesses deters growth rather than encouraging it. Labour counters that short-term pain is necessary for a more stable future. But workers and owners on the ground find this line less and less comforting.

The Bank of England has trimmed interest rates twice this year, but borrowing costs remain relatively high. Markets don’t expect another cut this month. Many analysts think policymakers will sit tight until next year. That leaves families and companies in a holding pattern, unsure whether to invest or wait it out.

The bleak data has already hit currency markets. Sterling dipped slightly against the U.S. dollar after the GDP figures came out. Though the drop wasn’t huge, it adds to a sense of uncertainty. Meanwhile, imports and exports both fell in October, and analysts point to global volatility and domestic hesitation as factors.

Economists warn against focusing too heavily on one month’s statistics. Maybe the numbers will improve in December or early next year. But given how often experts have tried to soothe nerves with that kind of talk, skepticism is understandable. People have heard it before.

For now, the government must convince the country that its plan will eventually pay off. That won’t be easy. Ordinary people see rising bills, cautious businesses, and a lack of any clear upward momentum. The promise of a brighter tomorrow feels vague. If growth doesn’t pick up soon, expect louder grumbles from voters and more pointed questions from the media.

Britain’s economy needs a spark. Right now, though, it’s stuck in a loop of uncertainty. The numbers say: Back-to-back contractions. Consumers say: We’re not sure. Businesses say: We’re nervous. The government says: Trust us. None of these voices, alone, can change the narrative. But something needs to give, and soon. The country seems to be holding its breath, waiting for signs that this dip won’t become a slide.